My neighbors think my “dog” is perfectly trained. Of course it is—its battery never barks, never sheds, never dies. But beneath my kitchen floor, in a basement that smells like bleach and secrets, the last warm heartbeat I know—Buddy—fights for air he’s no longer allowed to breathe.

I make a show of docking TinDog on the porch so the HOA cameras can admire its chrome head tilt and polite, factory-approved wag. Across the cul-de-sac, Mr. Patel flashes a thumbs-up. The block’s Sterility Score posted green today; our little American dream—no pollen, no pets, no problems—remains intact.

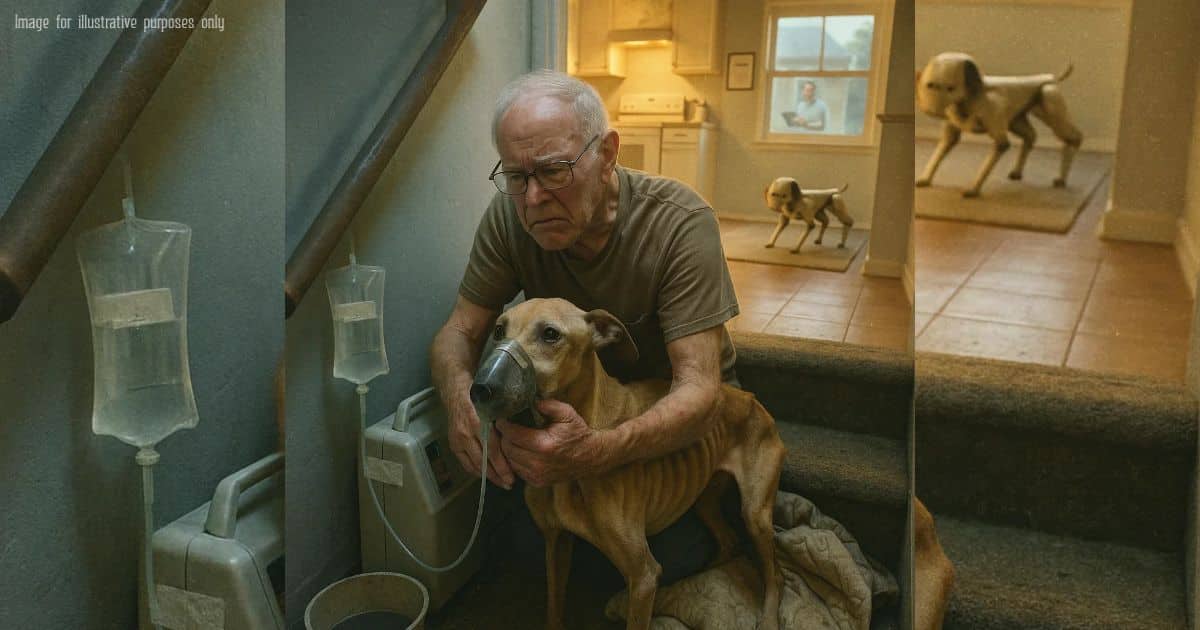

Inside, I slide the rug, lift the hatch, and drop into the cool hush I keep for the only living thing left in my life. Buddy raises his head, tail thumping once, as if his heart’s spent most of its strength already. The concentrator hums; the mask sits crooked because he hates it. I straighten it and rub the scar on his shoulder from the night I found him rooting behind St. Mark’s, when the world still pretended extinction was a strong word.

“Easy, bud,” I whisper. “I’m here.”

He coughs—a deep, tearing sound that pulls a string through my own chest. The gums are pale. His breath has that metallic edge Elena warned me about over a payphone three towns away. We’re out of time.

My wristband chirps: NOTICE: Sterility Audit may occur between 8–11 p.m. Randomization enabled due to minor anomaly.

My mouth goes dry. I kill the chime and start the ritual. HEPA to max. Ion scrubber to continuous. Vinegar mop—just enough to smell like cleaning, not enough to trip the algorithm that flags “scent masking.” I scatter a pinch of activated charcoal on the basement stairs—the only thing I’ve found that confuses the dander wand. I wipe Buddy’s paws with diluted antiseptic like I’m prepping a surgeon. He doesn’t fight. He never fights.

Doorbell. Not the harsh Department tone. The HOA chime that sounds like a smile.

Mrs. Keane stands there with her tablet and that realtor grin. “Arthur! Quick heads-up. Twelve-B dipped two points and triggered a random sweep. I told them you’re pristine. You always are.” She leans past me, peering for stainless bowls and silicone brush—props I keep spotless to prove my love for a machine.

“TinDog’s charging,” I say.

“Quiet little angel,” she coos.

From the basement comes the tiniest cough—the kind only someone who knows a body would notice. I nudge an old radio off the end table. It crashes. “Dang relics,” I laugh. “Buzz louder than my pacemaker.”

Her tablet blips AMBIENT AUDIO ANOMALY. She frowns at my doorway, then remembers neighborliness. “If they swing by, I’ll bring cookies.”

“Save the sugar,” I mutter, then, louder: “That’d be nice.”

When she’s gone, I check the time, recheck the downstairs, whisper to Buddy about Kansas and a doctor with brave eyes who still believes living things have rights. Saying “doctor” makes the kitchen speaker perk, so I shut up and hum “Stand by Me” like a man trying to convince the house he’s harmless.

The knock this time is the Department: two gray uniforms with the hexagon patch and a wand that breathes ozone.

“Evening, Mr. Hale. Random Sterility Audit. Shouldn’t take long.”

“Come in,” I say, and mean only as far as I cleaned.

They pet TinDog like it can feel it. The younger one grins. “My granddad had a Lab. This is better for him. Allergies.”

“Sure,” I say, because grief wears many disguises.

The older officer sweeps baseboards, vent returns, seams around the fridge. The wand sings low and satisfied—normal, normal, normal. He heads toward the hallway. My body angles to block him from the pantry, from the hatch in the floor that my wife once called “our secret to keep history in the house.”

He stops at the hatch anyway. Taps the seam. Adjusts sensitivity. The tone changes—not a siren, just curiosity clearing its throat.

“Anything down there?” he asks.

“Radon pit,” I say easily. “Spring thaw sets it off every year. I’ve got reports if you want to—”

The younger officer laughs at the word radon, like we’re old friends swapping cancer jokes in a waiting room. The older one studies his tablet. A big tempting button offers DEEP SCAN REQUEST. Another offers DEFER — FOLLOW-UP. Somewhere below, Buddy sighs—a soft exhale that carries up through boards and bones.

The officer looks at me like a man deciding whether to be a neighbor or a rule. He taps DEFER. The tablet pings green. “We’ll drop a canister tomorrow. Radon.”

“Can’t be too careful,” I say, and mean it in ways he can’t.

They thank TinDog. TinDog wags on command. The door closes. The lock slides. I stand, listening to the house settle back into its little digital prayers. Only then do I lift the hatch and climb down.

There, two feet from Buddy’s blanket, something small crouches on the concrete—shaped like a roach, the color of dust, a single red eye humming data. It turns toward me like it knows my name.

I step on it. The shell crunches. The red eye goes dark.

My flip phone buzzes in the coat I keep by the furnace—the coat with cash sewn into the lining and my wife’s note still in the pocket. Unknown number. A text:

If you want him to live, midnight. Blue Bridge. Come alone. Don’t trust the drones.

I look at Buddy. He looks at me like he always has, like weather is a promise I can make keep. Upstairs, TinDog finishes charging and plays a cheerful chime about compliance and tomorrow.

“Midnight,” I tell him. “We move.”

He tries to stand, legs trembling, then sinks, then tries again. I slip the old leather collar over his head, the one my wife bought the day she believed forever was still a word we could afford.

“We’ll make it,” I say, because sometimes a good lie is the truest thing you can offer a friend.

Outside, the neighborhood hums with perfect, sterile sleep. Inside my chest, something messy refuses to.

At midnight under the blue bridge, I’ll find out whether a living thing still has a right to breathe.

Part 2 — The Vet in the Ruins

Midnight tastes like old pennies and river fog. I park the ‘79 Ford two blocks shy of the blue bridge because the license plate doesn’t ping anything newer than a county barn and that’s how I like it. Buddy lies on the backseat in my wife’s quilt, sides working like bellows that forgot their job. I kill the lights and we drift in darkness, the truck ticking as it cools, the city above sleeping its sterile sleep.

Under the bridge, the paint flakes in ocean-colored scabs. Water gurgles through a grate the size of a confession. A shadow steps out from the concrete—small, steady, zipped into a coal-black jacket, hair pulled through a cap. The kind of person who keeps her words closer than her wallet.

“You’re Arthur.” Her voice is low, practiced flat. “I’m Elena.”

The name loosens my jaw because hope always surprises the body. “Doctor?”

“Used to be,” she says. “Now I’m a rumor.” She crouches by the passenger door and slides it open before I can move. “Let me see him.”

Her hands are fast but gentle, the kind people used to learn from mothers and clinics. Analog stethoscope, penlight, a fingertip oximeter old enough to be honest. The numbers on its tiny screen make something behind her eyes tighten.

“SpO₂ in the mid eighties. Lungs sound like crumpled paper. Fever.” She touches the collar my wife bought and nods toward the bridge’s blue ribs. “They tracked that roach drone to you before you crushed it. We have ten minutes, maybe less.”

“Ten minutes for what?”

“To move,” she says. “And to decide whether you want a miracle or a mercy.”

I look at Buddy. He looks back like he always has—no judgment, just attendance. “Miracle, then mercy if miracle fails.”

Her mouth does the ghost of a smile. “Fair.” She yanks open a tackle box full of syringes that aren’t meant for fish and draws up a clear liquid. “Dexamethasone. It’ll buy us a few hours. Maybe. I need his weight.”

“Forty-five pounds before the cough. He’s less now.”

She measures by eye and splits the dose. Buddy doesn’t flinch at the needle. He never flinches when I’m the weather in the room. She follows with a bronchodilator nebulizer mask that hisses like a kettle. After a few breaths, the zipper sound in his chest eases half a tooth.

“You kept him alive a long time,” she says without looking at me. “Most folks panic. They smother with love and Lysol.”

“I tried vinegar,” I say, and for a second we are just two people with the same stupid jokes.

A wash of white light swims across the river wall. A drone, quiet as a moth. Elena’s head snaps up. “Move,” she says, and we do—Buddy and quilt into the wagon I hid under a tarp, wheels squeaking like mice. She throws a sheet of mylar over him that crinkles like Christmas. “Heat mask,” she says. “Not perfect, but better than that quilt.”

We snake through the reeds to the far ramp, then cut behind an abandoned feed store to a lane of dead semis and rust. Behind a stack of shipping containers tagged with scripture and profanity, she unlocks a blue box with a blue door. Inside: a sink, a cot, a humming bank of machines with taped-over logos, jars labeled in tidy block letters—chlorhexidine, amoxicillin, saline—an altar for heresy.

“Welcome to the practice,” she says. “By donation only.”

I lay Buddy on the cot. He licks my knuckles like I’m a fact, not a man. Elena tapes a line to his foreleg, hangs a bag of fluids, rigs a cheap oxygen mask with a strip of T-shirt to make it fit. The air turns to plastic and hope.

“What is it?” I ask. “What exactly is killing him?”

Her eyes move across the machines as if they’re a language. “Combination of things. Years of sterile living collapsed our immune training wheels. They called it SSIA—Sterile-Shelter Immunity Atrophy—when we started seeing it in rescues. Add in the filters and aerosols shredding alveoli like confetti; throw in outlawed vaccines no one bothered to stockpile. You take away the complex, you get fragile.” She looks up. “Buddy’s lungs are losing their deal with air.”

“Can you fix it?”

“Not here. Not fully.” She flicks open a metal case and pulls a vial with a label so old it’s yellowed. “I can buy time. What he needs is in Kansas.”

“Sunflowers and tornadoes?”

She taps the vial. “A retired federal K-9 facility outside Fort Riley. When the ban came down, a few of us tried to preserve more than memories. We banked sera, microbiome seeds, old titers—bits of the living library. The Department shut most of it. There’s one storage wing we think they mislabeled and forgot.” She slides me a dog-eared map printed on paper that smells like a basement. Her finger traces a back road that hugs a river like a tired friend. “If we can get the polyclonal stock and a microbiome starter, I can build him something like a real immune instruction manual. It’s ugly medicine. It might work.”

“Why me?”

She shrugs. “Because you were brave enough to stomp a drone and kind enough to keep a secret. Because I can’t leave here without losing the last clinic in three counties. Because you look like an old man nobody stops if he drives the speed limit and smiles.”

“Because I’m disposable,” I say.

“Because you’re invisible,” she corrects. “Different currency.”

The Ford’s keys weigh in my pocket like fate. “How many hours do we have?”

“On a good run? Forty-eight.” She nods to the IV. “I gave him a steroid and he’s responding. The clock is loud but not hopeless.”

A soft chiming trickles from her laptop—an ancient brick wired to a nest of cables aimed out a slit in the door. She glances, then turns the screen for me to see. It’s my block’s community thread—digital neighborhood watch. A post from K. Keane, HOA: Ambient anomaly at 14C earlier. Department conducted random audit. All clear for now. Praise the Score. A reply underneath with a wavering camera phone clip: the underside of my rug, illuminated by a curious flashlight. The hatch seam gleams like a guilty smile.

“Who—?” My throat goes dry.

“Your neighbor’s kid,” Elena says. “Theo. Not a snitch. Curious. He uploaded to a closed group. I have a ghost on the city fiber that watches for your address since last month.”

“Last month?”

She doesn’t flinch. “PetKind flagged your warranty profile for outlier behaviors—manual overrides, unplugged mic windows. Someone in their Risk group shared the list with the Department.” She gives me a look that has both apology and calculus in it. “Your daughter works there, doesn’t she?”

The air shrinks. I sit because standing feels like a lie. “We haven’t talked in a year,” I say. “Longer, if you count talking that doesn’t end with one of us hanging up.”

“I’m not judging.” Elena checks Buddy’s gums again. “I’m saying your window is smaller than you think.”

Outside, a drone hum rises and falls—searching, curious, bored. She slips a needle into another vial and looks at me like a surgeon asking for consent. “I can sedate him lightly. Travel will be easier on his lungs. It carries risk.”

“How much risk?”

“Enough that we do it only if we’re walking out the door.” She points to the map. “You follow the river. Avoid the interstates. You stop here—an old feed co-op. They’ll trade you eight gallons of filtered water for a TinDog charging cable. Do you have one?”

I think of the mat, the hum, the neat little lightning icon. “Yes,” I say, and it feels like treason and relief at once.

She tapes a packet to the map: amoxicillin, prednisone, atropine, a sharpie list of doses in big letters someone my age can read at three a.m. “Don’t use the atropine unless he tanks. Then it’s one shot and prayer.”

“What about you?” I ask. “If they trace that roach drone to the bridge—”

“They already did,” she says. “But they think I’m a fisherman. And I move.” She nods at the containers. “Everything here rolls. That’s the point.”

A blue smudge crawls higher on the slit window, growing brighter—the lazy sweep of a searchlight coming around for another look. Elena picks up the syringe and the mask. “Decide,” she says.

I look at Buddy. He meets my eyes with the trust of a creature that never learned suspicion like we did. I nod. “We go now.”

She slips the needle in. Buddy’s body loosens in stages like a fist unclenching. His breath slows, not easier—just fewer. She tightens the mask strap. “We carry him to your truck on three. One—two—”

The blue light widens, licking the door seam. The clinic fills with a faint electrical buzz—the sound of a system paying attention. Elena freezes. Somewhere on the far side of the containers, a hinge squeals. Metal kisses metal. Boots? Wind? You can taste fear when it’s fresh.

“Change of plan,” she whispers. “We wait for the sweep to pass.”

Buddy exhales, long and rattly, then catches, then… doesn’t. The line on the oximeter dips and holds. Elena’s hands are suddenly on his ribs, her ear to his chest.

“Buddy?” I say, as if names are spells.

“Apnea,” she snaps. “Side effect. It happens.” She rips the mask off, tilts his head, seals her mouth over his muzzle, breathes. “Count.”

“One—two—three—” I press his chest the way she shows me, heel of my hand, two fingers below the point where a dog keeps his secrets. His fur is warm. His stillness isn’t.

Outside, the sweep stops. The blue glow hardens under the door like dawn coming where dawn shouldn’t. Something lands on the roof with a soft metallic thunk.

“Again,” Elena says, and we move in a rhythm older than laws: breath, press, hope, repeat.

“Seven—eight—nine—”

The oximeter flatlines in tiny red numbers that refuse poetry. From the yard, a speaker crackles—polite, official, empty. “This is the Department of Biointegrity. Blue container. Open the door.”

“Ten,” I say, and on ten his chest is still a stubborn grave. Elena’s hand dives for a laryngoscope. Outside, a gloved knuckle raps the steel three times like a judge about to read a sentence.

Part 3 — Neighborhood Watch

The polite voice outside becomes a fist. “Blue container. Open. The. Door.”

Elena’s hand is on Buddy’s ribs; my hands are where she put them, two fingers off the sternum point, pushing the way you do when you’re begging a locked heart to try the handle again. The oximeter glows stubborn red. The blue glow under the door fattens like dawn arriving too soon.

“Tube,” Elena snaps. The laryngoscope flashes silver. She slides a narrow cuff past his tongue with the grace of muscle memory. “Bag.” She jams a rubber bulb into my fingers. “Every four seconds. No more. You push too fast, you blow him out.”

I squeeze. Pause. Squeeze. The mask huffs. Buddy’s chest rises in little, delayed hills. Somewhere above us, metal ticks as something heavy steps onto the roof.

Elena flips a switch on the wall. A compressor kicks in; a faint chemical sting creeps into the air, sharp and cold—ammonia. She rips duct tape off a vent, funnels the smell toward the door seam. “HazMat buys us seconds,” she says. “They step back before they break in.”

The speaker outside barks again—less polite. “Container occupant, step away from the door. Biointegrity Protocol.”

“Bag,” she reminds me, and that becomes my world: four-beat math, plastic squeal, the small rise that keeps hope measurable.

Boots scuff. The blue beam stutters. The speaker switches tones—consultation with a different manual. “Positive ammonia signature detected. HazMat en route. Maintain position.”

Seconds. That’s what we bought.

“Move,” Elena says. She wheels the IV pole, slaps a portable tank into a canvas sling, then grabs the cot handle. There’s no room to turn, no grace to it. We shove Buddy—tube taped, lines taped, the whole delicate miracle taped—toward the back wall that looks like corrugated steel until she kicks a hidden latch and a square of metal pops like a tongue from a cheek.

A throat into the next container, dark and tight. She shoulders through, hauls the cot, and I crawl behind with the oxygen and map packet under my shirt. In the second container, everything is wrong: a wall of crab pots, plastic bait buckets, a pegboard of rusted hooks—props for a life no one lives here. Elena slams the hatch, throws a tarp over the cot, and spins me into a corner where a roll-up door sits half-open to a lane of shadow between two forty-foot boxes.

“Truck,” she says. “On my signal. Left, then right, then straight to the river road.”

“What about you?”

She shakes her head. “Somebody has to open the front, stall them, and make this smell make sense.”

“Come with us,” I say, and she looks at me like a woman who burned that wish up a long time ago keeping other people alive.

“I’m more useful if I’m a rumor,” she says, and presses a cheap flip phone—the twin of mine—into my palm. “When you hit the co-op, text ‘hay’ to that number. They’ll open the back gate. Stay off the interstates. If you see orange drones, cut your lights and stop breathing.”

She raises the door an inch more. Outside, river fog snugs the ground. A train horn cries somewhere upriver—three short, one long, lonely as church bells. The blue sweep skims past the lane mouth, then hacks right again, patrolling its circle.

“Go,” she whispers.

We run. The cot’s wheels complain. The canvas sling digs into my shoulder. The tube tape snags my sleeve and my heart tries to leave my body to beat for Buddy since he’s busy. At the alley’s mouth, I see the Ford two lots down, a silhouette with a dented smile. We bolt. I catch the handle, wrench the door, muscle the cot in half, and slide Buddy onto the quilt. I prop the tank upright, jam the BVM between my knees, and bag, bag, bag.

Elena’s shadow is already receding. She ducks back between the containers and vanishes like a person remembering how to be air. A second later, the blue washes the front of the first container, a door squeals, and the speaker outside coughs: “Sir, ma’am—HazMat—please wait—” Someone swears when the ammonia opens their sinuses to tomorrow.

I start the Ford. The old engine catches in a grumble that sounds like blasphemy and mercy at once. We roll with lights off until the river road unspools like a dark ribbon and the bridge falls behind us and the drones shrink to irritated stars.

On the dashboard, the flip phone Elena gave me buzzes once—no text, just a pulse like a hand squeezed and let go.

I drive and bag. Bag and drive. The rhythm becomes a metronome for everything I failed to save and might still.

Back in the neighborhood, the Watch doesn’t sleep; it scrolls. Elena’s laptop sees it all because she’s tapped into a slice of fiber no one remembers to patch. The thread blooms like kudzu.

K. Keane — HOA: Unusual traffic by the river. Possible encampment. Alerting Department.

J. Patel: Heard sirens near the Blue Bridge.

Theo M. (kid account, posting under his mother’s login): please don’t hurt the dog

K. Keane: Theo, sweetheart, we don’t have dogs here.

G. Mori: I saw a man with a wagon earlier. Looked… old. Scary.

R. Cruz: We used to help the old. Remember?

Anonymous (new account): All pets must be registered. We all agreed. Standards keep us safe.

The thread becomes a ping-pong of fear and memory. Someone posts an archived flyer from ten years ago: “Community Picnic — Bring your pets!” Half the comments refuse to believe it was ever real.

A different network lights up twenty miles away—in a building with glass walls and living moss floors that make executives feel human. PetKind’s Crisis Room pings incident content flagged. An auto-summarizer prints: possible organic canine — unverified — proximity to 14C Maple Bend. Maya Hale, Director of Communications, touches her screen and the clip opens: a jittery flashlight sweep across a rug, the glitter of a hatch seam, the edge of an old leather collar with a brass ring, then the camera jerks up and the video ends with a child’s sharp inhale.

She doesn’t breathe for three beats. It’s not the dog that hooks her. It’s the rug—the handmade one her mother crocheted from torn T-shirts one winter when money fell through the floor. She’d know those faded blues anywhere. She’d know the chip in the hatch paint where, at twelve, she’d dropped her father’s hammer and he’d laughed instead of scolded.

“Ma’am?” a junior analyst says from the doorway. “We should notify Risk. If organic exists near corporate HQ, the Department—”

“Send me the raw,” she says too soft. “I’ll… draft.”

He leaves relieved. She pinches the screen until brass fills it. The tag on the collar is just out of focus. She tilts the phone like that would solve time. Her thumb hovers over Call Dad and then falls away because the last time she pressed that button they made it fourteen seconds before breaking each other.

She opens the internal chat to Risk. hey raj — can you send me the “outlier” list again? something’s off with one address. He replies with a file and a joke about her insomnia.

There he is. Hale, Arthur — manual overrides — CAM mics disabled — TinDog warranty void pending inspection. The notes are clinical. They might as well be a report on a stranger.

She closes her eyes and sees their first dog, Scout, pushing his warm head under her hand after her mother’s funeral, bringing her a sock like a white flag of peace. She sees her father building the ramp for Scout’s hips when the old dog’s back end gave out. She hears herself, six months ago, saying, “Dad, it’s safer now. You could get a TinDog. You’d like it.” She hears the click when he hung up.

In the truck, the road unwinds into corn stubble and billboard bones. The Ford hums. Buddy’s tongue shows the color Elena didn’t want to name earlier. I keep the rhythm anyway, four seconds, press, release, watch his chest move, believe it means what it used to mean.

The Ford’s old radio, possessed by ghosts and distant AM, scratches out a late-night show. A caller whispers about seeing a coyote at the edge of a parking lot and not knowing whether to call a hotline or keep a secret. The host says, “Maybe secrets are how we remember we’re still people.” The static eats the rest.

The flip phone in my pocket buzzes. A text: detour — checkpoint ahead — flashers on the county road. Elena’s ghost in the fiber again. I ease the Ford down a gravel spur choked with foxtail, headlights off, engine idling rough as an old man waking. A convoy of gray SUVs rolls past at parade speed. My hands sweat around the plastic bag mask.

When the road is empty of certainty again, we crawl back out and make the left, then the right Elena inked onto the paper that smelled like basement. The river hangs a silver thread out my window. The sky begins to bruise toward morning.

On Maple Bend, Mrs. Keane stands in my driveway at dawn with a Tupperware of cookies and eyes that want to be kind. She knocks. She texts. She posts: Arthur isn’t answering. Anyone seen him? He’s usually up with the birds. Six houses over, Theo tapes a drawing to my door: a dog with a blue collar and a big SHHH across the top.

In the Crisis Room, a second clip hits Maya’s screen—this time from a roach drone’s last, dying frame: a close, blurred view of gray fur, a human hand pressing a chest, the shine of a tear on knuckles that look like her father’s.

Her throat closes. She types three words to Risk and deletes them. She types three others: hold escalation 12 hrs and hits send before she can think about jobs or laws or how fear makes people small.

I drive. Buddy’s chest rises again—thin, late, obedient. I count to four and squeeze. On the map taped to my dash, a star sits over an old feed co-op that Elena circled and labeled water/fuel/humans. If we make that, we buy a day. If we buy a day, we can buy another.

Behind us, the blue bridge shrinks to a rumor. Ahead, Kansas is still a word and not yet a distance. I keep the Ford between the lines and the breaths between the seconds. It’s not hope. It’s work shaped like hope.

At PetKind, Maya stares at the frozen roach frame until it feels like a mirror. She reaches for her phone, hovers over Dad, then chooses Unknown Caller mode and dials the number Elena uses to haunt the fiber.

When Elena answers, Maya says, “If he’s who I think he is, tell him to avoid the I-70 toll cameras. And tell him I’m not his enemy.”

She hangs up, closes the blinds on the room with the moss wall, and for the first time since her mother died, lets herself say the small, dangerous word out loud.

“Dad.”

And on the river road, as the sky thins toward light, a county cruiser pulls out from behind a silo, eases onto my bumper, and flips its bar to blue.

Part 4 — Road to Kansas

Blue eats my rearview. The cruiser settles on my bumper like a hand on a shoulder that doesn’t mean comfort.

I slow, signal, pull onto the gravel shoulder. The Ford shudders to a stop. Buddy’s breaths are shallow under the mask; the IV bag licks the dome light with its small ocean. I put the bag-valve mask between my knees, wipe my palms on my jeans, and practice being ordinary.

The deputy walks up slow, hat brim a black horizon. Not the gray suits—county. Her flashlight paints my mirror, then my hands on the wheel.

“Evening,” she says. “License, registration. You know your right taillight’s out?”

I hand her everything except the truth. “Didn’t know. Sorry.”

She tips the beam inside. It touches the oxygen tank, the taped tubing, the quilt, the shape beneath it. The light pauses on the leather collar at Buddy’s neck—old brass, my wife’s last purchase that wasn’t a bill. One beat, two. She could call Biointegrity with a thumb.

“What’s in the back?” she asks.

“Oxygen,” I say. “For a friend.”

“Friend got a name?”

I look at the mask fogging in small, honest circles. “Buddy.”

She cuts the flashlight, rests her knuckles on the door frame, and leans an inch closer like she’s smelling something only she remembers. “You from around here?”

“Maple Bend,” I say.

“Used to have a K-9 in this county,” she says, staring past me at the road like it might answer. “Name was Juno. He knew more law than three rookies. When the ban came down, they gave me a brochure with a coupon code.” She swallows. “You know what a brochure can’t do? Look you in the eye.”

Behind us, two gray SUVs prowl past, government plates blank as a poker face. The deputy keeps her stance. She says, too loud for their mics and just soft enough for me, “I’m writing you a warning for a taillight. I’m going to walk back to my car. When I get there, my dashcam is going to… glitch. My radio is going to need a reboot. If someone asks, you turned left onto County 12. If you actually turn right, you’ll miss the checkpoint.” She taps my window glass with the edge of her finger, a private gavel. “Drive slow. If you see orange striping on the drones, get under a tree. They scan heat.”

“I don’t know how to thank you,” I say, and we both know the currency is not words.

She starts to turn, then leans down again, softer still. “You got four, five hours before the day shift starts stacking roadblocks. There’s a co-op on the river road, Peterson Feed. They don’t sell to the Department. Tell Nora Denise sent you. She’ll get you water.” A beat. “And… if anyone asks, I never liked brochures.”

She peels off, climbs into her cruiser, and the blue dies like a bad idea. I count to ten because it makes leaving feel less like running. Then I roll back onto blacktop, signal right, and actually turn right.

A mile later, a hand-painted sign boards a sagging fence: PETERSON FEED & SEED — WATER — DIESEL — CASH / TRADE. A tired rooster crows from a mural of better days. I nose the Ford beside a string of tractors old enough to vote. The smell is dust, oil, river, and a little hope.

Inside, a bell rings. Fans thrum. Shelves hold salt blocks, dog-eared almanacs, sacks of corn with patriotic bald eagles stenciled on them like we’re still pretending. A woman with forearms like fence posts and a braid of gray rope looks up from a ledger. Her name tag reads NORA in stamped tin. A teenager behind her counts bolts in a coffee can like it’s a meditation.

“Morning,” Nora says. “Which Denise?”

“County deputy,” I say. “Sends regards. I… need water. Maybe diesel. I can trade.” I hold up the TinDog charging cable like a man surrendering a passport.

Nora whistles softly through her teeth. “That thing’s worth eight gallons easy.” She flicks a look at the boy. “Migs, pull eight. And grab the foam cooler.” To me: “Your friend in back human?”

I shake my head. Lie would be easier. It wouldn’t be kinder. “He’s a dog.”

Migs freezes like I said a ghost. Nora’s eyes flick to the door, the windows, the little black dome in the corner that might be a camera or just a dead fly glued to plastic.

“Don’t say that word in here,” she says evenly. “We sell livestock supplies. We sell nostalgia. We don’t sell trouble.” She moves faster than I expect for someone with rope for hair, coming around the counter and through the door with me before the bell has time to decide what song to play. At the truck, she peels back the quilt a corner. Buddy’s chest rises, shallow and true. His muzzle is gray where it wasn’t last spring.

Nora inhales like a memory just hit her and she didn’t ask it to. “We had a Blue,” she says. “He used to round up the kids when the tornado sirens went. Got them under the table before we knew the sky had made up its mind.” She drops the quilt. “Alright. Water. Diesel. And you can have this.” She thrusts the foam cooler at me. “Ice. You’ll need to keep meds cold when the sun stops pretending it’s polite.”

Migs arrives with blue jugs like small planets. He tries not to stare. He fails. “Sir,” he whispers, “my aunt says the last real dog died in ‘47.”

“Don’t tell your aunt everything,” Nora says, not unkind. To me: “Map says you’re running the river. Good. Follow the silos. Drones don’t like metal. If you hit the old Waffle House—yellow sign without the W—take the dirt road behind it. Cuts two miles and a camera. You’ll come up near the county line. After that it’s you, corn, and whatever God remembers.”

I hand her the cable. It feels like parting with a tooth that doesn’t hurt yet.

“Keep your receipt,” she says with a grim little smile, and writes nothing on a scrap of paper that means everything.

On the way out, I leave two twenties on the counter because, whatever we call it, this is a sacrament. Nora pretends not to see. Migs pretends not to learn.

Back on the road, the map Elena scrawled smells like wet basement and pencil. I tape it to the dash with a strip of medical tape and do the math out loud. “Fort Riley—seven hours if the world is kind. The world isn’t kind. Nine, ten.” The Ford is a faithful liar; it says it can do anything.

Buddy’s ears twitch under the mask when the radio skates past a station playing “Stand by Me.” He doesn’t know the words. He knows the weather of my voice humming along. When the sedative eases off, he wakes into little flurries of panic and I bag with the rhythm Elena taught me until the panic passes and the breaths turn into work again.

Midday, the sun flexes. Heat ripples off the road like a rumor. I see my first orange-striped drone, lazy in the thermals, indifferent predator. I throttle back, under a cottonwood, engine barely a heartbeat. A farmhouse across the field wears a FOR SALE sign that’s been sunburned illegible. A kid’s bicycle skeleton rusts beside a mailbox. The drone roams on; we do not breathe until it forgets us.

I text hay to the number Elena loaded. Ten minutes later, a gate at the co-op’s back lot clacks open. A man with a scar like a question mark ushered us through with two fingers from a pocket. He fills our tank from a farmer’s stash and never learns my name. I hand him a tin of coffee from behind my seat. Currency adjusts.

In another town, a church marquee reads: SUNDAY: GOD LOVES YOU. MONDAY: WE’RE CLOSED. Under it, two women in scrubs smoke in a patch of shade and laugh the exhausted laugh of people who know what triage tastes like. I consider stopping. I keep the Ford rolling. The most dangerous thing in America is a story with too many witnesses.

By late afternoon, the land leans toward Kansas. Grain elevators grow like white castles, throwing long shadows across fields that learned loneliness before we did. The map says a left. I take it. The sign says FORT RILEY — RESEARCH ANNEX in a font that means: Go away unless your badge beeps.

The K-9 facility sits behind a wedge of chain link and razor wire that glitters like a threat. The guard shack is empty, or looks it. A camera the size of a thumb watches the entrance with a patience I envy. A faded mural of a shepherd wearing a badge still clings to a cinderblock wall, nose up, ears forward, forever on duty for a country that retired him with a coupon.

I kill the engine a hundred yards out and let us roll into a stand of sumac. The air is cricket and hot metal. I take the binoculars I kept from a birding phase that lasted exactly two afternoons and scan the fence. To the right: a section of panel bowed where a cottonwood has been shoving its shoulder for years. Above it, a strand of wire hangs slack like a tired grin.

I whisper like a man in church. “We go there.”

Buddy stirs, as if the word there is a place he already knows. I fix his mask, check the lines, tuck the IV bag under my shirt to hide it from cameras that can read fluids like scripture.

I belly-crawl the last twenty yards and push the IV ahead of me like a strange, precious flag. The fence tastes like dust and winter on my tongue as I press myself into it and find the bolt that gave up first. With the Leatherman my wife gave me on our twenty-fifth anniversary, I twist and twist until the metal sighs and something gives in a way that matters.

We slide through: me first, then the tank, then the old dog who never asked to be brave and is anyway. Inside the perimeter, the world smells like disinfectant with the memory of wet fur—like when you clean a bathtub a day after a life swam in it.

The kennel row is a low rectangle of cinderblock with runs that open to concrete lanes. The drain grates still hold a few blonde hairs sealed under varnish of time. Stenciled letters over a door read: RESEARCH ANNEX 7B — BIOINTEGRITY STORAGE — AUTHORIZED PERSONNEL ONLY. A keypad waits like a little, square god.

I press my ear to the metal and hear nothing human. Then—faint, flicked like a penny tossed into a fountain from far away—something barks.

Not the recorded bark they used at petting zoos before petting zoos became museums. Not the shrill play-you-in bark. A single, hoarse sound that carries chest and stubbornness. Buddy’s ears lift. His eyes widen the way hope widens.

“Tell me you heard that,” I whisper to no one and to everyone I’ve ever loved.

A shadow cuts the sun in a straight line across the concrete. I look up. A drone, not orange—military flat, purposeful—slides over the kennels and stops. It tilts. It stares. My pocket buzzes once.

Unknown number. Three words.

Don’t. Move. Dad.