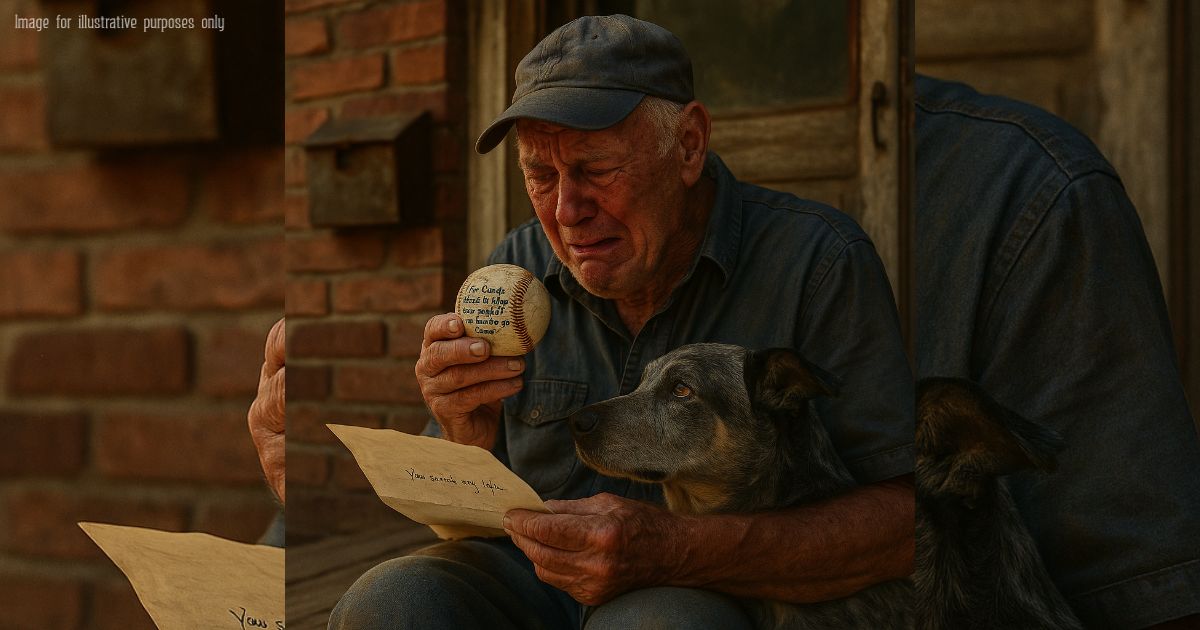

Late August 2025, Maple Street Park has gone to seed. On the bleachers, Emmett rubs June’s braided whistle while Mutt holds third like a lighthouse—minutes before a mailbox delivers a scuffed baseball and five words that will rewrite twenty summers.

Part 1 – The Letter in the Dust

By the last week of August 2025, Maple Street Park in Ashland, Ohio had gone to seed. Goldenrod nuzzled the backstop. Crabgrass stitched the basepaths shut like a stubborn seam.

Coach Emmett Riley eased down the first-base line with a slow man’s care. He wore the same sun-faded cap he’d worn for twenty summers, its brim whitened with salt and memory. Beside him trotted Mutt, a speckled blue heeler mix with one ear nicked like a torn ticket stub, coat sprayed with ash-gray freckles, and eyes the color of creek stones after rain.

At the chalk ghost of third, Mutt stopped. He sat square and patient, tail making a small metronome in the dirt. He looked outward, always outward, toward home.

“Afternoon, Third Baseman,” Emmett said, and his voice came out rough from disuse. The nickname had arrived the same year his knees started talking back. The dog accepted it without question, like a good player taking a sign.

The air smelled of sun-warmed dirt and a faint tang of iron from the old chain-link. A line of maples on the far side whispered with cicadas. Somewhere a mower droned on another block, and the sound made Emmett’s hand go to the braided lanyard at his chest.

The whistle hung there, brass and quiet. June had braided that lanyard from the leather thongs of an old mitt the summer before the cancer showed its full face. “Make it you,” she’d said, working the strands with her sure fingers. He hadn’t blown the whistle since the funeral. Some tools keep their shape by staying silent.

He lowered himself to the low bleacher step and pressed both palms to his thighs before sitting. The boards grumbled. He let his breath find its slow work. On the field, dust motes danced in the sunlight like tiny boys stretching into fly balls that would never land.

Mutt’s tail thumped, then stilled. Vigil settled over him like a blanket. He never looked back to check on Emmett. He never needed to. That was the thing about the dog—he faced forward like the inning had already begun.

Emmett lived three streets over in a one-story brick with a porch too big for one chair. He kept a fungo bat by the front door, its barrel scarred soft by a thousand easy arcs. He still carried it sometimes out of habit, but today he’d left it leaning in the umbrella stand. “You don’t need to show off,” he’d told himself in the mirror, the way you talk to old bones before the weather turns.

The boys had been men to him even when they were only eleven, too big for their cleats and too small for the shadows that followed. He could see them if he let himself. Owen Tran with the easy wrists. Marcus Hale, who laughed too loud and ran too far because home was a place he couldn’t reach except by rounding third. Jalen Merriweather, who showed up with bruises he swore came from sliding, and whose eyes gave the lie. And a quiet kid named Tino Alvarez, who always said thank you to the grass.

Emmett pulled at a tuft of crabgrass beside the bleachers until its white roots came free like a thread from a sweater. He rolled the roots between thumb and forefinger. “Weeds remember,” he murmured. “They climb back to where the light used to be.”

He looked at Mutt. The dog was stock-still, chest rising and falling, nostrils barely flaring. If there were ghosts, Mutt counted them. The dog had no flair for tricks, no appetite for fetch. His gift was staying. He was a lighthouse set down in the infield, blinking a steady yes at time’s tide.

A small boy on a bicycle drifted by on Maple Street, glanced in, and pedaled faster. Two houses down, Mrs. Dorothy Kline watered her petunias and pretended not to look. She was the sort to complain to the city about the field and then leave a plastic bowl of water by the third-base coach’s box when no one was around.

“Afternoon, Dorothy,” Emmett called, because naming people was its own kind of mercy. She lifted her hose in half-salute and went back to the petunias. Water spattered the dry dust with the patient rhythm of a rookie learning the strike zone.

Emmett rubbed the whistle between finger and thumb. The leather was soft and dark where June’s hands had taught it shape. He could still smell a memory of neatsfoot oil and the ghost of her perfume, something floral and earnest. June had loved the sound of boys hollering on summer nights, the way a town’s heart beat louder when the lights came up. “You save them one practice at a time,” she’d said, when he fretted over a boy who wouldn’t go home after dark. “You save them by giving them somewhere to be.”

He didn’t save them all.

That was the secret, the thing that kept him awake in the deep hours when the refrigerator hummed like a far-off crowd. He had benched a boy once—Tyson Reed—for talking back when the boy’s world was already blowing apart. He had called a father once and said, “We don’t yell at boys here,” and learned you can light a match in a room full of fumes. He had driven Jalen around for an extra twenty minutes after practice, pretending to look for a lost glove, just to give time for the house to cool down.

“Third Baseman,” he said softly, “we did what we could.”

Mutt didn’t move. His ears twitched at something only he could hear. The tail gave one soft thud, like a mitt on a knee.

A breeze came up from the west and pushed the smell of the VFW hall toward the field—fry oil, cigarettes, and yesterday’s stories. The elm shadow in shallow left shifted, and a glint flashed at the edge of the basepath. Emmett rose carefully and walked out, his shoes making delicate prints in the dust where boys had used to dig in.

Half-buried in the dirt was a safety pin, twisted open, with a blue plastic bead still threaded on it. All-Star pins. He had handed them out on a July night fifteen summers ago, when the mosquitoes were drunk on blood and hope. He turned the pin in his palm and let it prick him. It was a clean pain, the kind that says you’re still here.

He put the pin in his pocket with other small archaeology. In a coffee tin on his kitchen counter sat two button backs, a broken shoelace tip, a penny from 1978, and a Snapple cap that read “Baseball was invented by…” and lost the rest to rust.

Down Maple, the U.S. Mail truck coughed and pulled away from his block. The sound hooked something in him. He looked at the dog.

“Postman’s been,” he said. “Think there’s anything for old ghosts?”

Mutt glanced back at him, which he rarely did at the field. The dog stood, performed a slow stretch that unrolled his spine like a page being turned, and padded over. He leaned his shoulder to Emmett’s calf as if to say, We’ll go together, then.

They walked home the long way, which meant down Cedar where the barbershop’s pole no longer turned and past Mercer Hardware with its “For Lease” sign bleached almost white. The sun sat high and unblinking. Emmett’s knee sang its steady ache, an old hymn with too many verses.

At his mailbox, he worked the rusted latch like a balky catcher’s mask. Inside lay bills, a coupon for tires he didn’t need, and one thick envelope the color of old infields. The return address was a city far from Ashland, and where a logo sat embossed on the flap, silver caught the light the way stadium lights catch sweat.

He stood very still, the world narrowing to the weight in his hand. Mutt nosed the envelope once, then settled at his feet, patient as ever.

On the porch, Emmett slit it with his thumbnail and slid out a letter and something round wrapped in tissue. The tissue rolled away to reveal a baseball, scuffed honest, with a blue-ink message across the leather he could read without his glasses.

“For Coach Emmett Riley,” it said, “who taught me how to go home.”

His breath left him like a man caught looking at a curveball. He unfolded the letter. The first line was written in a hand that had learned patience somewhere past the fences of Ashland.

You saved my life.

Mutt’s tail thumped once, then again, more insistent, as if someone had just waved him around.

Part 2 – A Place to Belong

The words trembled in his hands like something alive.

You saved my life.

Coach Emmett Riley sat back in the porch chair, the old webbing groaning under his weight. Mutt pressed close to his shin, tail sweeping once, twice, steady as a pendulum. The dog didn’t look at him, only out toward the street as though guarding the moment from interruption.

Emmett let the letter settle across his lap. He was in no hurry to turn the page. Some truths had to breathe a little before they could be read aloud to the heart.

The handwriting was firm but not hurried, each loop deliberate. It carried the weight of someone who had learned how to sign for children’s baseballs and tax forms and maybe even contracts that bent the shape of a life. The ink bled just a touch where the pen had pressed too hard, as if the words had refused to stay caged.

Emmett cleared his throat, though no one was there to hear him, and began.

Coach,

You might not remember me. My name is Tino Alvarez. I played third base for you in the summer of 2009. I was small, quiet, and not much of a hitter. But you kept me on the roster. You let me stand out there and wait for grounders, and you shouted my name like I was worth the saying. That summer, you gave me something no one else did: a place to belong.

My father was gone. My mother was tired. Home was not safe. But the field—your field—was a refuge. You never asked questions you shouldn’t, and you never made me feel less than I was. You told me once, “Third base is all about waiting for what’s coming. Don’t be afraid of it. Just keep your glove down.” I’ve carried that ever since.

Coach, I’m writing to tell you I didn’t just play another season. I kept playing. I played in high school, then college. And last year I signed with the Cleveland Guardians. I’m their third baseman now. I guess I was waiting for the grounder long enough, and when it came, I was ready.

But that’s not the point of this letter. The point is, I made it because of you. I made it because you gave a scared kid a place to stand. You saved my life. And I want to thank you the only way I know how. I want to come home and rebuild Maple Street Park. I want you to see third base alive again.

If you’ll let me, I’ll come soon. Tell me if the field is still there. I hope it is. I hope you are, too.

—With gratitude, always,

Tino

Emmett folded the letter closed, though the words kept glowing in his head like stadium lights warming a dark lot. He leaned forward, resting elbows on knees, and stared at the baseball on the porch table. The ink curved across the leather in a bold scrawl: For Coach Emmett Riley, who taught me how to go home.

He whispered the name, tasting the syllables like something half-forgotten. “Tino Alvarez.”

The dog pricked his ears.

“You remember him, don’t you, Third Baseman?” Emmett asked. “Quiet boy. Small gloves. Kept his hat too low.” Mutt’s tail ticked, as if memory were alive in his bones.

Emmett closed his eyes. He could see the boy again, crouched in the dust, knees bent just so, glove low to the earth. He’d been so slight that a strong gust might have toppled him. But he never flinched. Not from bad hops. Not from boys who laughed. Not from fathers who barked from the sidelines. He simply waited, glove open, ready for what came.

And now that boy was a man, grown enough to write with steady words and promise a gift that felt too large for Emmett’s small, quiet life.

The whistle tugged at his chest like an anchor. He let his hand fall against it, thumb rubbing the smooth brass. “June,” he said, voice hushed, “you’d like to hear this.”

The porch wind carried no answer but the rustle of cottonwoods down the block. Still, he imagined her smile, the one that had always told him his stubbornness was a kind of grace. She’d said once that coaching was just parenting with extra dirt. He hadn’t believed her then. He believed her now.

Mutt rose suddenly and padded down the steps to the yard. He sat facing west, ears alert, as though sensing something moving through time itself. Emmett followed his gaze, but the street was empty save for the afterglow of late afternoon.

The letter lay heavy in his pocket. He stood, knees stiff, and went inside.

The house smelled of liniment and coffee that had gone stale on the burner. The walls held team photographs in cheap frames: boys frozen mid-summer, eyes shining with the hope of futures not yet hardened. He had hung them like saints in a chapel. Some faces he could name without thinking. Others had slipped away into the blur of seasons.

He set the baseball on the mantel beside June’s picture. She looked out at him, smiling from under a straw hat, sunlight caught in her hair. The ball seemed right at home there, a bridge between memory and what might still come.

He reread the letter twice more before setting it down. His chest ached with something he hadn’t felt in years—not quite joy, not quite sorrow. More like the shock of a lungful of air after too long underwater.

At the kitchen sink, he splashed his face with cold water. His reflection in the window startled him: white hair, deep creases, eyes that seemed older than the rest of him. Could he stand on a field again? Could he watch boys—or men—play where ghosts still ran?

Mutt came in, nails ticking on the linoleum. He nosed Emmett’s hand, insistent. The message was clear: don’t drift too far inside yourself. The world was waiting.

“You’re right,” Emmett said softly. “Always forward.”

He sat at the table with a notepad, the kind with a magnet that kept it stuck to the fridge. His pen shook a little, but the words came steady.

Tino—

The field is still here. Overgrown, but here. I am, too. Come home when you can. We’ll be waiting at third.

—Coach Riley

He sealed the envelope before doubt could tell him otherwise.

That night, he dreamed of chalk lines reappearing under his hands, of boys’ voices echoing like bells, of Mutt trotting toward third with tail flying high. He woke with the whistle warm against his chest and the sound of the dog’s breathing steady by the bed.

In the days that followed, something shifted. Word must have traveled, though Emmett never said a thing. Mrs. Kline lingered longer at her fence, asking cautious questions. “Did I hear right, Coach? One of your boys in the big leagues?” He nodded, and she smiled like a girl again.

At the hardware store, the clerk slipped a pair of work gloves into his bag without charge. “For the field,” he said, eyes darting away, embarrassed at kindness.

The town, half-forgotten, began to stir. A place remembers its own heartbeat if you tap it just right.

Emmett and Mutt returned to Maple Street Park each afternoon. The dog still sat at third, vigilant. But now Emmett walked the bases, pulling weeds with his gloved hands, dragging a rake across the infield dust. It was slow, backbreaking work, but it felt like prayer. Each patch of cleared dirt was a confession answered with forgiveness.

Children came one evening, curious. A boy and a girl, maybe ten years old. They watched from behind the chain-link. “Is this the old field?” the girl asked.

“It’s the only field,” Emmett said.

They slipped inside, cautious at first, then freer. The boy ran the bases with his arms spread wide like wings. The girl picked up a stick and pretended to swing. Laughter filled the air. Mutt barked once, sharp and glad, and settled back down at third like a judge satisfied with the court.

When the children left, Emmett sat in the bleachers, tears sliding down the lines of his face. He hadn’t expected the sound of play to cut so deep. It was like hearing a song you thought lost forever.

A week later, the mail came heavy again. Another envelope, thicker, bearing the Guardians’ crest. Inside was a plane ticket and a date.

Tino Alvarez would be home on September 12th.

Emmett held the ticket, fingers trembling, and Mutt leaned against him with the weight of certainty.

For the first time in years, Coach Riley felt the season turning not toward endings, but beginnings.

And somewhere in the distance, though the field lay empty, he could almost hear the crack of a bat and the roar of a crowd rising like a hymn.

Part 3 – The Season Turns

The plane ticket lay on the kitchen table like a miracle made of paper. Emmett Riley traced the letters with his finger—Cleveland to Columbus, arrival September 12. He hadn’t held a ticket to anything in years. Not to a game, not to a concert, not even to the county fair. Life had become the kind of thing you didn’t need tickets for: church suppers, doctor’s visits, slow mornings that ended where they started.

Mutt sat at his feet, head heavy on Emmett’s boot, as though anchoring him to the floor.

“You hear that, Third Baseman?” Emmett said, voice rough. “September twelfth. Boy’s coming home.”

The dog’s tail brushed the linoleum in a steady rhythm, agreeing with time itself.

In the days that followed, Emmett felt something stirring inside him that he hadn’t known in decades: anticipation. It was different from dread, different from habit. This was forward-looking, and it made his chest ache with the strange weight of hope.

He carried the ticket in his shirt pocket, checking it more often than he wanted to admit. At the post office, he slipped it out once just to reassure himself it was real. At the grocery store, when the clerk asked if he needed help with the bags, he nearly said, No, but I’ve got a major leaguer coming to town. Instead he just shook his head and carried the bags himself.

Every afternoon, he and Mutt returned to Maple Street Park. The field was still ragged, but the shape of it had begun to reemerge. Each weed he pulled, each stone he tossed aside, was like uncovering a bone in the skeleton of memory. Soon, you could see the faint diamond again, a geometry of loyalty.

Sometimes neighborhood kids came. Not many—just a few curious ones who’d never seen the field alive. One boy, maybe twelve, asked, “You gonna fix it up, Coach?”

Emmett paused, leaning on his rake. “Not me. We.”

The boy looked puzzled. “Who’s we?”

Emmett’s eyes drifted to Mutt, stationed faithfully at third. The dog sat regal, chest out, watching the boy. “You. Me. Anyone who cares about baseball. Anyone who cares about home.”

The boy smiled shyly and kicked at the dirt, then bent to pick up a handful of stones. He carried them to the fence and dumped them outside. Just like that, the rebuilding had begun.

Nights were hardest. Anticipation made it hard to sleep. Emmett lay awake with the whistle cold against his chest, listening to Mutt’s breathing. He remembered boys who’d passed through his care like fireflies—bright, brief, unforgettable. Some had gone on to lives he knew nothing about. Others he heard about in whispers: a prison sentence, a car accident, a war they didn’t return from.

“You don’t save them all,” he whispered to the dark. “But maybe you save one.”

The thought brought him peace enough to close his eyes.

September drew closer. The town seemed to sense it. Mrs. Kline stopped him at the fence one morning. “Coach Riley,” she said, “do you need lemonade for the workers?”

“Workers?”

She pointed toward the park, where three teenagers were hacking at weeds with borrowed hoes. “Looks like word’s out.”

By the next week, there were more—men with wheelbarrows, mothers with coolers of water, retired fellows like Emmett who knew how to measure out chalk lines by eye. The field was coming back alive. Not perfect, but breathing.

And through it all, Mutt stayed faithful at third base. He did not bark, did not chase, did not wander. He simply sat, guarding the corner like the anchor of the infield. Children laughed and sometimes tried to coax him to play, but he only wagged and stayed put. Third base was his altar, his post, his calling.

On September 11, the eve of the promised day, Emmett walked the field alone at dusk. The air smelled of cut grass and fresh chalk. He carried the whistle in his hand, rolling it back and forth. The field was not finished, not polished, but it was whole enough to remember itself.

“Almost time, June,” he whispered. “Almost time to see one of our boys come home.”

He felt her absence keenly then, like a seat left empty in the bleachers. But he also felt her presence in the lines of the grass, in the leather braid of the whistle, in the steady beat of Mutt’s tail against the dirt.

The dog was waiting at third, watching the horizon. The light dimmed, the cicadas droned, and the town held its breath.

Morning came. September 12.

Emmett woke early, dressed in his cleanest shirt, and walked with Mutt to the park. A small crowd had already gathered—neighbors, former players now gray at the temples, children with mitts too big for their hands. They stood awkwardly at first, as if afraid to speak too loudly.

Then, at 10:15, the sound of a car rolled down Maple Street. Heads turned. A black SUV pulled to the curb, the kind that looked out of place in Ashland. The door opened, and a tall man stepped out.

He wore jeans, a Guardians cap pulled low, and a smile that was both nervous and certain. His shoulders were broad now, his arms roped with muscle, but the eyes were the same—dark, steady, waiting for what came.

“Tino,” Emmett whispered.

The man spotted him at once. His smile broke wider, and he started across the grass. He didn’t wave. He didn’t call out. He just came, steady as a ground ball rolling home.

The crowd murmured, then cheered. Some clapped. A few wiped their eyes.

But Mutt was the first to move.

The dog leapt from his place at Emmett’s side and ran—not toward the crowd, not toward home plate—but straight to third base. He skidded to a stop there, tail whipping furiously, body vibrating with recognition.

Tino Alvarez froze. His mouth opened, then shut. He stared at the speckled blue heeler mix guarding the base.

“That’s…” He blinked, voice breaking. “That’s the same dog.”

The crowd hushed. All eyes turned to Emmett.

“Yes,” the old coach said. His throat felt thick, but his voice carried. “Mutt’s been waiting.”

Tino walked slowly to third. He crouched down, big-league knees folding like a boy again, and reached out. Mutt sniffed his hand once, then leaned into it with a low, contented groan. The dog’s tail thumped the dirt where chalk would soon be drawn.

The sight cracked something open in the whole town. Applause turned to shouts, cheers, even sobs. It wasn’t just a reunion. It was proof that loyalty could outwait time.

Emmett stood back, tears sliding unchecked down his weathered cheeks. For the first time in years, he let the whistle rise to his lips. He gave one sharp, clean blow.

The sound rang out across Maple Street Park, bright as a bell, clear as truth.

And the season, long dormant, began again.

Part 4 – The Field Remembers

The whistle’s echo hung in the air long after the sound itself had died.

Children clapped their hands over their ears, laughing. Old men nodded solemnly, as if they’d been waiting years for that single note. Women wiped at their eyes with the edges of shirts and aprons.

And Mutt—faithful, stone-still Mutt—sat proud at third, as if to say, This is where we begin again.

Tino Alvarez straightened, brushing the dirt from his hands. His face shone with a mixture of boyish awe and man’s resolve. He looked around at the gathering crowd, then back at Coach Emmett Riley.

“Coach,” he said, voice thick, “I came home to build.”

The crowd answered with a cheer that rolled across Maple Street like thunder.

Emmett nodded once, too choked to speak. The whistle dangled at his chest, trembling with the rhythm of his unsteady breath. He managed only: “Then let’s get to work.”

The days that followed blurred into something like a second youth.

Pickup trucks arrived at the park, beds piled with lumber, rakes, seed sacks, chalk bags. Retired men from the VFW lugged steel benches to replace the rotted ones. Women from the church brought potluck casseroles and lemonade in sweating jugs.

Children swarmed like ants, eager to help, hauling stones, chasing each other down baselines not yet drawn. Their laughter knitted the place back together stitch by stitch.

Tino rolled up his sleeves and labored alongside them. Fame seemed to fall away at the first swing of a hammer. He worked the way he must have played—steady, disciplined, without complaint. Every so often, he’d stop to sign a ball or pose for a picture, but mostly he hauled and hammered.

“Big-league muscles come in handy after all,” one of the men teased.

Tino grinned. “Coach Riley taught me early—keep your glove down, your head up, and your hands busy.”

That got a laugh, but Emmett only smiled, quiet and inward. He hadn’t realized until then how many words he’d sown in boys who were now men. Words planted deep enough to bloom years later, when he wasn’t looking.

By the second week, the field had a shape again. Fences straightened. Bases anchored. The pitcher’s mound rose like a small hill of promise. A fresh infield mix of red dirt spread under the sun, glowing like new clay in a potter’s hands.

One evening, as the sun bled orange across the trees, Emmett walked the diamond alone. His knees ached with each step, but he forced himself onward. Home to first. First to second. Second to third. He paused there, beside Mutt, whose vigil had never wavered.

“You kept it warm,” Emmett murmured, brushing the dog’s head. “Kept the light on when I couldn’t.”

Mutt leaned against his leg, steady as a post.

Emmett’s eyes lifted to the dugout. Freshly painted green, it looked almost new. But he could see ghosts sitting there—boys with caps too big, gloves too stiff, faces too eager. He felt June beside him, her hand resting lightly on his arm. She’d be proud, he thought. Proud of the field. Proud of Tino. Proud even of him, for still standing here.

One afternoon, Tino called everyone together in the bleachers. The whole town seemed to turn out, sitting shoulder to shoulder, children perched on laps. Mutt lay sprawled at third, watching from a distance.

Tino held a microphone borrowed from the high school. “I want to thank all of you,” he began. His voice carried strong, confident, yet humble. “This park raised me when life was rough. This man—Coach Riley—gave me the ground under my feet when I had none. And now, together, you’ve given me the gift of bringing it back.”

The crowd erupted in applause. Emmett, sitting in the front row, lowered his head. His cheeks burned with embarrassment, but his heart swelled with something he couldn’t contain.

Tino raised a hand for quiet. “I’d like to dedicate the rebuilt field to the man who made us all believe in second chances.”

He gestured toward Emmett. “From now on, this will be known as Riley Field.”

The roar was deafening. People stomped their feet, clapped, whistled. Some shouted Emmett’s name. The old coach covered his face with both hands, shaking his head.

“You can’t do that,” he muttered.

But the crowd insisted. And in the stands, a handmade banner unfurled, painted in bold letters: WELCOME HOME, RILEY FIELD.

Mutt barked once, sharp and loud, as though sealing the christening with his own approval.

That night, Emmett couldn’t sleep. He sat on the porch with the whistle in hand, turning it in the moonlight. The dog rested at his feet, head heavy on his boot.

“I never asked for a name on a field,” Emmett whispered. “All I ever wanted was a place for boys to run.”

He thought of the ones who hadn’t made it. Tyson Reed, Jalen Merriweather, Marcus Hale—faces that still haunted him. He wished they could see the field now, reborn and alive. He wished June could see it most of all.

But maybe, he thought, they did. Maybe loyalty and memory stretched wider than a man could measure.

He blew the whistle once, softly, a note meant only for the ghosts. The night air carried it out across Maple Street, and for a heartbeat, he swore he heard voices answering from the dark.

As September wore on, the work neared completion. The outfield grass shone emerald, seeded and watered daily. The dugouts were finished. The scoreboard, though old, stood tall after a fresh coat of paint.

The town planned a reopening game for early October. Little League boys and girls would take the field, and Tino himself would throw the first pitch. Word spread beyond Ashland. Local newspapers promised coverage. Even a television crew hinted at coming.

Emmett felt the weight of it, both heavy and light. He worried his knees wouldn’t let him stand long. He feared the emotions would buckle him. But beneath the worry was something sturdier: pride, not in himself, but in the miracle of a field that remembered its own heartbeat.

One afternoon, just weeks before the reopening, Tino found Emmett sitting alone in the dugout. The sun was low, painting everything gold.

“Coach,” Tino said gently, “can I tell you something?”

Emmett nodded.

“I never told anyone this, not even my mother. That summer in ’09… I almost gave up. On everything. I was angry, scared, tired of being nobody. But you—” His voice broke. He steadied it. “You kept me. You saw me. That saved me.”

Emmett swallowed hard. “I didn’t do much, son. Just gave you a glove and a place to stand.”

“That was everything,” Tino said. He reached into his pocket and pulled out a small object. It was a pendant, silver, shaped like home plate. He pressed it into Emmett’s hand. “I had this made my rookie year. I kept it close. But it belongs to you.”

Emmett turned it over, heart hammering. On the back, etched in neat letters, were the words: For Coach Riley—who taught me how to go home.

His throat closed. He tried to speak but only managed a nod. Mutt trotted up then, as if sensing the moment, and sat at his feet. The dog’s tail brushed the dust, a quiet drumbeat of affirmation.

Tino smiled, crouched to scratch Mutt’s ear. “He never left third base, did he?”

“Never,” Emmett said, voice steady now. “Not once.”

They sat in silence as the sun went down, the field stretching wide around them, a cathedral of earth and memory.

That night, Emmett dreamed again. Boys in crisp uniforms ran bases. June stood in the bleachers, clapping her hands. And Mutt, ageless, eternal, waited at third, tail wagging, eyes bright, a guardian of loyalty and time.

When he woke, the whistle gleamed on his chest, and the sound of morning filled the air. He rose slow, knees aching, but with a heart light enough to carry the day.

The field was almost ready. The season was almost here.

And for the first time in many years, Emmett Riley believed he was ready too.