Part 7 – The Weight of the Innings

October melted into November, and the air sharpened in Ashland. Leaves skittered across Maple Street Park, catching in the fence like stray balls. The field was still green enough, still alive, but it carried the smell of endings, of a season turning over.

Coach Emmett Riley pulled his coat tight as he walked the basepaths with his cane. Mutt padded beside him, nose to the dirt, tail flicking. The dog stopped automatically at third base, sitting like a stone marker against time.

“You’re faithful, Third Baseman,” Emmett murmured, lowering himself onto the bleacher. “More faithful than these knees of mine.”

He eased down, lungs rattling from the short walk. His chest carried that old pressure again, the one that came at night, the one he’d tried not to admit. The whistle hung cold against his skin.

But when the children showed up—gloves swinging from their wrists, voices shrill with excitement—the pain lifted, if only a little.

They’d started coming every afternoon after school, without needing to be asked. The town had taken to calling it “Riley League,” though no papers had been signed, no board formed. Just kids gathering, throwing balls, running bases, playing until the sun dimmed.

“Coach Riley!” a girl named Marissa shouted one day, sprinting up with her cap crooked. “You gonna hit us some flies?”

He lifted the fungo bat, though it felt heavier now than it had the week before. “Flies? You think you’re ready for flies?”

“Yes, sir!” she said, eyes bright.

“All right, then,” he said, setting a ball on his palm. “Gloves up.”

He swung, the crack echoing across the park. The ball arced into the sky. Children scattered, voices rising. Mutt barked once, approving, then returned to his post at third base.

For an hour, the world was whole again.

But afterward, when the children left, the ache in Emmett’s chest returned sharper. He sat on the bleacher gripping the whistle, sweat beading along his brow though the air was cool.

“Not much time left, boy,” he whispered to Mutt. “Not much at all.”

The dog pressed close, eyes searching, as though he could will his master’s body into strength again.

A few nights later, Emmett collapsed on his porch. One moment he was carrying in the mail, the next he was on his knees, gasping.

Mutt barked frantically, circling him, pawing at his chest. The noise drew Mrs. Kline from across the street.

“Emmett!” she cried, rushing over. “Hold on, I’m calling 9-1-1.”

He waved her off, gasping. “No hospitals. Just… help me sit.”

She steadied him against the porch post until his breathing eased. He shook his head, pale and trembling.

“Don’t you scare us like that,” she scolded softly, tears in her eyes.

“I’ll be fine,” he lied.

But that night, lying in bed with Mutt curled close, he knew the truth. His innings were short now.

The next day, Tino came by, face lined with worry.

“Coach, you should’ve called me,” he said, kneeling beside the porch chair.

Emmett waved him off. “Don’t fuss. Just a stumble.”

“Coach,” Tino said firmly, “I need you to take care of yourself. The kids need you. I need you.”

Emmett’s eyes softened. “I’m not much use anymore.”

“That’s not true,” Tino said, voice thick. “You’re the reason any of this exists. You’re the reason I exist. Don’t you dare tell me you don’t matter.”

Silence hung between them. Mutt’s tail thumped once against the porch floor, as if seconding the truth.

At last, Emmett nodded. “All right, son. I’ll hang on as long as I can.”

The days grew shorter, colder. Practices became fewer, but children still came, stamping their feet in the frosty dirt, breath clouding. They wore mismatched mittens and caps pulled low.

Emmett hit fewer balls, but he gave more words. He called encouragement, offered advice, told stories of summers past. He taught them not just how to play, but how to wait, how to face what came with their gloves low and their hearts steady.

One evening, after the last child left, Tino stayed behind. They sat on the bleacher together, the field silvered with moonlight.

“Coach,” Tino said, “I think we should set up a permanent foundation. Riley League. Scholarships, uniforms, travel money. Everything these kids need.”

Emmett chuckled. “You think anyone’s gonna pay for a foundation named after an old man and his dog?”

Tino smiled. “They already are, Coach. They already have.”

Emmett looked at him long, then nodded. “All right, son. If it keeps the game alive, I’ll give you my name.”

Mutt barked once from third base, tail flicking like punctuation.

But even as the league grew in spirit, Emmett’s body faltered. His cough deepened. His steps slowed. More often, he sat rather than swung. Children didn’t mind—they crowded around him in the dugout, listening to his stories like sermons.

One day, a boy asked, “Coach, why does Mutt always sit at third?”

Emmett smiled faintly. “Because third base is where you face what’s coming. It’s the last stop before home. You wait there, glove ready, and you don’t flinch. That’s what Mutt’s teaching us.”

The children fell quiet, looking toward the dog, who sat steady as ever in the fading light.

December crept in with snow. The field slept under white, but the kids still came, throwing snowballs where the bases lay buried. Emmett watched from the bleachers, bundled in his coat, Mutt pressed close against his legs.

The cold bit at his lungs, but he stayed. He wanted to see the field alive, no matter the season.

One afternoon, as the sky turned gray, Emmett leaned down to Mutt. His voice cracked.

“When I go, boy… you stay. You keep third base warm. Promise me.”

The dog licked his hand, tail brushing the snow. A vow.

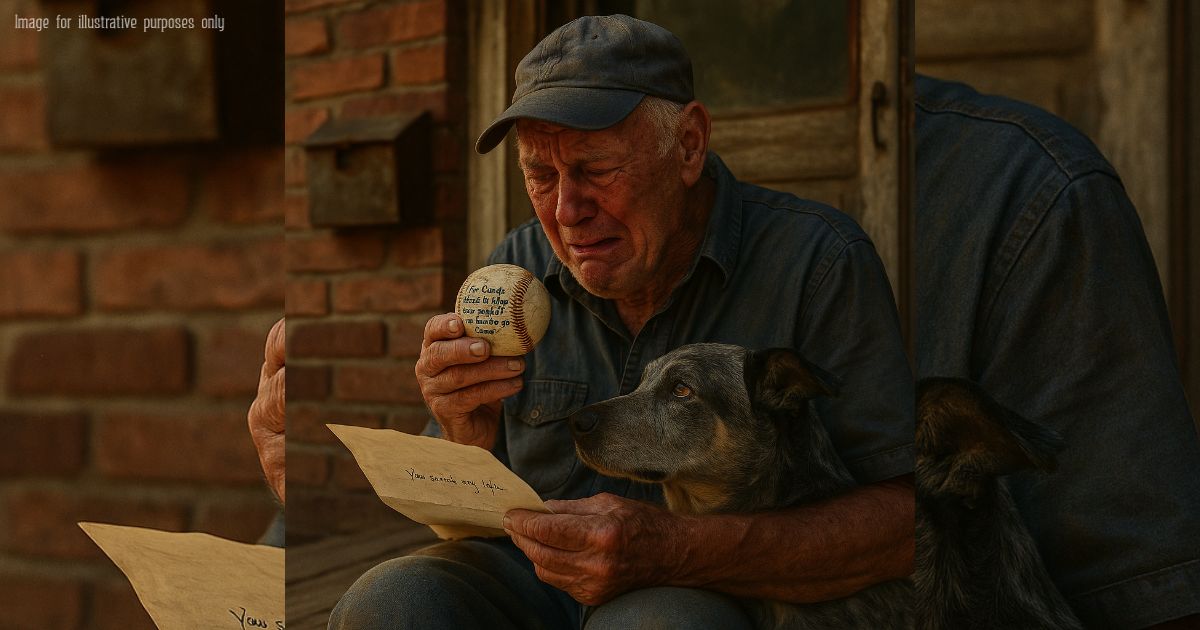

That night, Emmett lay in bed, weaker than before. He held the whistle in one hand, the pendant Tino had given him in the other.

“You saved my life,” the boy had written. Emmett wondered if, in some way, the boy had saved his, too—saved these last months from being only silence.

Mutt curled against his chest, breath steady, anchoring him to the earth.

Emmett closed his eyes and whispered, “Always forward, Third Baseman. Always forward.”

And the dog’s tail thumped once in reply, keeping time with a heart that beat slower now, but still strong enough to hold one more inning.

Part 8 – Winter’s Vigil

Snow fell heavy that December, muffling Ashland in white. The town slowed, but Maple Street Park remained alive in its own quiet way. Children trudged through drifts to toss snowballs at invisible bases, their laughter fogging the air. The field, though buried, still remembered.

Coach Emmett Riley sat on the lowest bleacher wrapped in a wool blanket. Mutt pressed against his leg for warmth, breath steaming. The dog’s fur was grayer now, muzzle frosted not with snow but with age. Yet his eyes burned bright, and his place at third remained unbroken.

“Don’t know who’s older, you or me,” Emmett muttered, rubbing the dog’s head. “But we’re both stubborn, aren’t we?”

The dog’s tail tapped against the frozen wood. Yes. Stubborn as winter itself.

By mid-December, Emmett rarely walked the bases anymore. His lungs fought the cold, and his legs trembled after only a few steps. He carried the whistle under his coat, but it felt heavier now, as if it knew time was short.

Still, the children gathered. They didn’t care about drills anymore—couldn’t even play proper ball in the snow. Instead, they sat in a circle around the old coach, listening to stories.

He told them of the summer of ’72 when the team won the county championship. He told them of a boy who once broke three bats in a week because he swung with such fury. He told them of June, how she had braided the whistle’s lanyard from an old mitt, how she believed the field was holy ground.

The children listened wide-eyed, snowflakes gathering on their caps. For them, he wasn’t just a coach. He was a living story.

One evening, after the kids had gone, Tino lingered. He crouched in the snow, watching Emmett struggle to stand.

“Coach,” he said softly, “maybe you shouldn’t come out here in the cold.”

Emmett bristled. “And miss the game?”

“There is no game,” Tino said gently.

“There’s always a game,” Emmett shot back, voice cracking. He gestured toward third, where Mutt sat, steady as a sentry. “As long as he’s there, the inning isn’t over.”

Tino’s eyes burned with tears. He reached out, steadying the old man’s arm. “Then let me carry you through it, Coach. You’ve carried us long enough.”

Christmas came. The town lit candles in windows, wreaths on doors. At Riley Field, a group of children placed a wreath on the fence behind third base. Red ribbon fluttered in the wind.

“Why there?” someone asked.

“Because that’s where Mutt waits,” a little girl answered. “That’s where Coach watches.”

Mutt sniffed the wreath, then sat down beside it, tail brushing the snow.

Emmett, standing a few yards away, felt his chest break open with something too large for words. He whispered, “They understand, June. They really do.”

But winter cut deep. January brought ice storms that rattled windows and made walking treacherous. Emmett stayed inside more often, staring out at the field through frost-glazed panes.

Mutt would whine at the door, torn between his loyalty to Emmett and his pull toward third base. Sometimes, when the old man slept, the dog slipped out through the cracked porch door. Emmett would wake to find him hours later, snow clinging to his fur, eyes fixed on the empty field as though guarding it in the night.

“You’re keeping vigil for both of us,” Emmett murmured, drying him off with an old towel. “Good boy.”

The dog leaned into his hands, heavy with devotion.

One night in late January, Emmett’s chest pain returned sharper than ever. He collapsed onto the floor, gasping. Mutt barked, frantic, pawing at him, nosing the whistle against his lips as if urging him to blow it.

With shaking hands, Emmett clutched the whistle but couldn’t lift it. The world blurred.

When he opened his eyes again, he was in his chair, a quilt over him. Mrs. Kline sat beside him, face pale. “You can’t keep scaring us like this,” she whispered.

He nodded weakly. He wanted to argue, to insist the innings weren’t done, but the truth pressed heavy.

The town began to rally around him without being asked. Meals appeared on his porch. Neighbors shoveled his walk. Children stopped by after school, sitting on the steps to tell him about their days, their games, their dreams.

And still, every afternoon, Mutt went to third base. Even when snow lay knee-deep, he dug out a hollow, sat firm, tail sweeping slow. Townsfolk walking past pointed and said, “There’s loyalty, right there. There’s faith.”

The story spread. An article in the Ashland Gazette called him The Dog Who Waits at Third Base. Strangers came to see him, bringing biscuits, snapping pictures. But to Mutt, none of that mattered. His vigil wasn’t for show. It was for Emmett. For the game. For home.

One bitter February evening, Emmett sat on the porch wrapped in blankets, Mutt beside him. The sky was lavender, the air brittle. He looked at the dog long and hard.

“You know, boy,” he whispered, “one day soon I’ll be gone. But when I go, I reckon you’ll still sit there. You’ll wait, just like always. And maybe that’ll be enough. Maybe that’ll remind them what loyalty looks like.”

The dog lifted his head, eyes reflecting the last of the sunset. His tail thumped once, steady, like a promise sealed in silence.

Emmett closed his eyes, listening to the sound. It was stronger than his own heartbeat now.

March crept close, but Emmett grew weaker. He rarely left the porch. Yet the children kept the field alive—shoveling snow, tossing balls, waiting for spring. Tino organized weekend practices, but always insisted they stop by the porch first to greet their coach.

One afternoon, a boy named Caleb asked, “Coach, are you coming back to the dugout when it’s warm again?”

Emmett smiled faintly, hiding the ache in his chest. “If the good Lord lets me, son.”

“And if He doesn’t?”

Emmett glanced at Mutt. The dog sat straight-backed at third, staring into the distance.

“Then you listen to him,” Emmett said. “He’ll teach you everything I can’t.”

That night, lying in bed, Emmett whispered to the dark:

“I’m not afraid, June. Just sorry to leave the inning unfinished. But maybe that’s what the dog’s for. Maybe he’ll carry it the rest of the way.”

Mutt shifted closer, pressing against him, tail thumping once.

And Emmett Riley, tired and frail but still holding the whistle, drifted into sleep as snow fell steady outside, covering Riley Field in silence.