Today, I laid down my tools for the last time.

After more than five decades of working with wood — shaping, sanding, carving — I’ve decided it’s time to retire. My hands aren’t what they used to be, and my eyes tire quicker these days. But more than the wear on my body, it’s the wear on my heart that’s brought me to this moment.

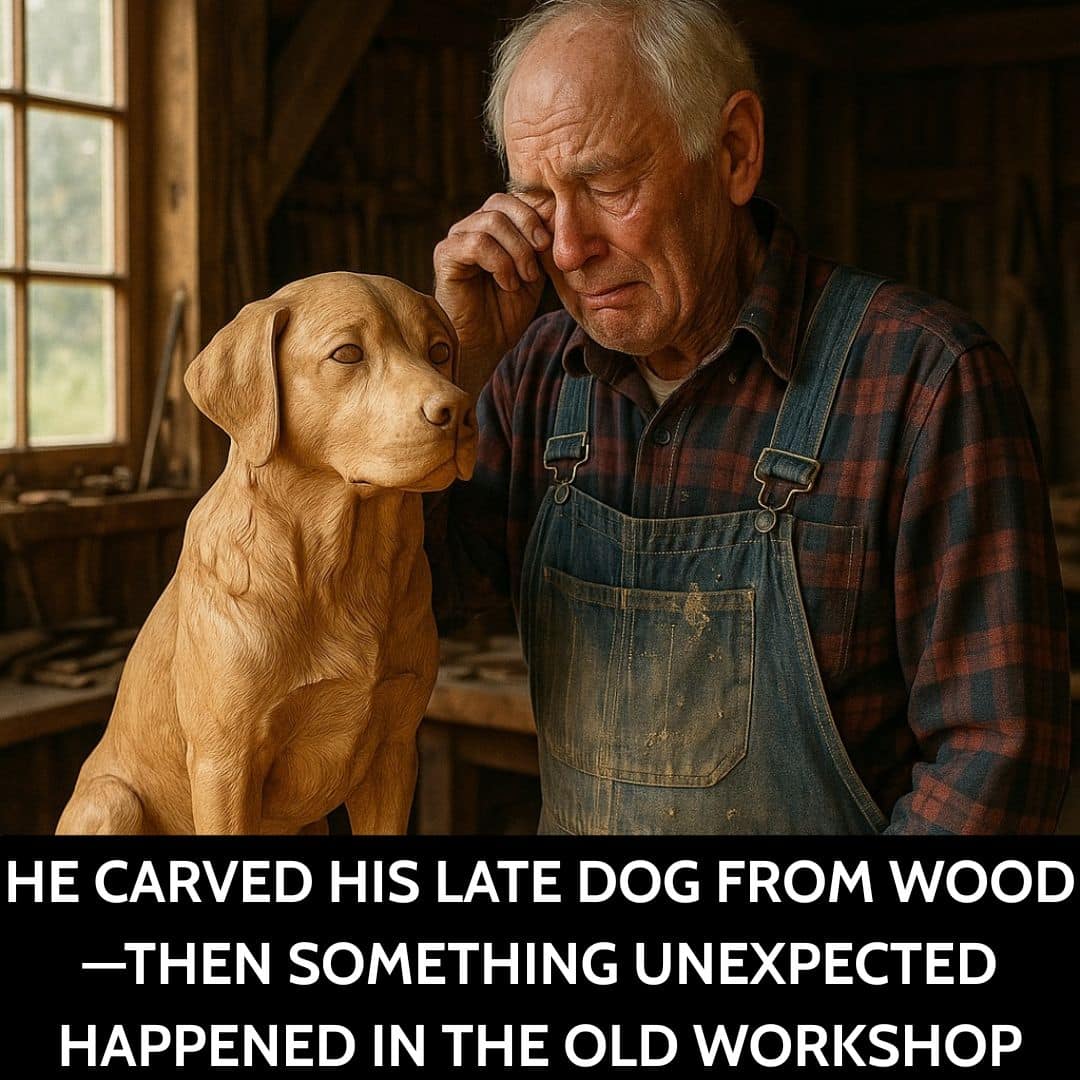

This dog here — the one on my workbench — she ain’t real, though I’ve tried to give her a soul. She’s carved from red oak, but to me, she’s alive. She’s my last piece. My final work. And she’s modeled after my girl, Daisy — my Labrador Retriever who passed away just a month ago.

She was with me every day in this workshop. Sat right by that wood stove every winter, tail thumping whenever I hummed an old tune. When I’d forget my lunch, she’d remind me with that look. And when the world felt cold or folks seemed distant, Daisy never was. She understood me in a way people don’t anymore.

It hurts, carving her like this — reliving every memory, every little detail. But it also helped. Helped me say goodbye.

I look around this old shop now, and it feels like the last leaf falling from a tree in late autumn. Most folks today wouldn’t care much for a place like this. The world’s moving too fast now — all screens, speed, and noise. No one seems to have time for the slow, quiet work of hands and heart anymore. Kids don’t want to learn it. People don’t pay for it. They’d rather buy something plastic and perfect than something made with love and sweat.

That used to bother me. Still does, if I’m being honest.

Sometimes I feel like a relic, like I belong to a time that doesn’t exist anymore. A time when a man’s word meant something, and his work was his pride — not his paycheck. When the marks on your hands were badges of honor, not signs of failure. Now, I look around and feel invisible.

But this dog… she reminds me that what we build — what we love — doesn’t vanish, even if the world forgets.

I made her with everything I had left in me. Not for money. Not for show. But for love. For Daisy. For me.

So here it is. My last goodbye. To my craft. To my best friend. And maybe, in a way, to the world I knew.

If anyone still listens to old men like me — remember this: the things worth keeping are rarely flashy. They’re quiet. Honest. Worn smooth by time and touched by love.

And sometimes, they sit on a workbench, looking back at you with wooden eyes that still seem to know your heart.

— Harold, age 74, retired carpenter

I didn’t expect to see anyone that day.

The rain had just let up, leaving the air thick with the scent of wet pine and old dust. I was sweeping out the corners of the workshop — not because it needed it, but because that’s what you do when your hands don’t know how to be still. I wasn’t carving anymore. That was done. But the habit of movement lingers, like a song that won’t leave your head.

That’s when I heard the creak.

The door. Slow. Hesitant.

I turned, expecting maybe a neighbor or someone dropping off firewood.

Instead, it was a kid. Couldn’t have been more than eleven. Freckles. Torn sneakers. Hair a mess. He stood there like he’d wandered into a church by accident.

He didn’t speak right away. Just stared at the dog on the bench.

I cleared my throat. “You lost, son?”

He shook his head slowly, eyes never leaving her. “She looks like she’s listening.”

Those words stopped me cold.

I looked at the carving again — at Daisy’s ears tilted slightly forward, her head angled just so, like she was catching something only she could hear.

“She was good at that,” I said, before I realized I was speaking. “Listening.”

The boy stepped closer. Careful. Respectful. I could tell he wasn’t the type to touch without asking. Good parents, or maybe just a good soul.

“What’s her name?” he asked.

“Daisy,” I said softly. “Was. She passed.”

“I’m sorry.”

I nodded. “Me too.”

He looked around, his fingers brushing the edge of the workbench. “Did you make all this?”

“Every gouge and splinter,” I said. “Fifty years’ worth.”

His eyes lit up, not in the way grown men’s eyes do when they see price tags or potential, but the way a match flares in the dark. Something about this place — the tools, the wood shavings, the quiet — seemed to settle him.

“My name’s Eli,” he offered.

“Harold.”

He smiled. “Can I come again?”

I wanted to say no. I really did.

What good would it do? The world didn’t need more carpenters. It had machines and mass production now. Boys should be learning code or video editing or whatever made money these days.

But then I looked at Daisy. At those wooden eyes that weren’t really hers — but somehow still carried her patience.

And I heard myself say, “If your folks are alright with it, I suppose.”

Eli grinned. “They will be.”

Then he was gone, boots squelching in the damp gravel, and I was left standing in the middle of my silent workshop, heart oddly loud in my chest.

He came back two days later.

Didn’t say much that time either. Just stood next to me while I sanded an old drawer I hadn’t touched in years. Asked a few questions. Watched more than he spoke.

I found myself pulling out my smaller tools, showing him how to hold them. How to feel the grain with your fingertips. How to listen to the wood — really listen — because it tells you what it wants to be, if you let it.

He was a quick learner. But more than that, he was gentle. And gentleness, in a boy that age, is something you don’t take for granted.

At one point, he asked, “Why did you stop?”

I paused. “Because my heart wasn’t in it anymore.”

He didn’t answer. Just reached out and placed his hand on Daisy’s wooden head.

“She misses you,” he said quietly. “I think.”

I didn’t know what to say to that. So I didn’t.

But later that evening, when the light had gone gold through the workshop window, I sat alone on the bench beside her. Just me and a dog carved from memory. And I whispered, “Maybe I miss me too.”

By the end of that week, Eli was showing up like clockwork.

Sometimes he’d come after school, his backpack still slung over one shoulder, smelling faintly of pencil shavings and peanut butter. Other times it was a Saturday morning, just as I was lighting the stove, bringing warmth back into the bones of the old shop.

He never came empty-handed. A book he wanted to show me. A sandwich he made himself. Once, it was a pencil drawing of Daisy — just a few wobbly lines, but her ears were right. I tacked it up next to the window without a word.

I didn’t tell him we were building anything.

Didn’t call it lessons. Didn’t call it teaching. But one afternoon, I slid an old piece of pine his way, and said, “Try your hand.”

He looked at me like I’d handed him a relic.

“Won’t I mess it up?”

“Of course you will,” I said. “That’s half the point.”

He carved slow. Careful. Every motion deliberate, like the wood might bite. His first attempt was rough — an uneven ridge that cut across the grain like a scar. He looked up, worried.

But I just nodded. “Now it’s yours.”

He smiled at that. A shy thing. And went back to carving.

Over the next few weeks, the shop changed.

There were two coffee mugs by the lathe now. A second stool dragged close to the workbench. Chalk lines and notes written in a child’s hand scattered between sawdust and shavings.

One day, I caught him tracing the letters on Daisy’s nameplate.

“She watched with love,” he read aloud. “So must we.”

I hadn’t told him what that meant. I didn’t need to.

“Do you think she’s proud of you?” he asked.

I had to turn away for a second. “I hope so, Eli.”

He ran a finger down her carved snout. “I think she’d like me.”

“She does,” I said. “She always had good judgment.”

That night, I pulled out a box I hadn’t opened in years.

Inside were my first tools — handles worn smooth, blades nicked and dulled. I’d kept them, not out of sentiment, but out of stubbornness. A part of me had always believed no one would want them.

But now…

I sanded the box clean. Oiled the handles. Sharpened what could be sharpened.

The next time Eli came, I handed it to him.

“For me?”

“For the work ahead,” I said. “She’s not the last thing to be carved in this shop.”

He opened the box like it held treasure.

I didn’t say anything more. Just turned back to the bench. My hands, once resigned to stillness, reached for a piece of oak.

And beside me, so did his.

That winter, I watched the fire glow across wood and skin. Eli’s hair grew longer. His hands grew steadier. And slowly, the silence in the shop became something different.

Not emptiness. But peace.

Something passed between us in those hours. Not just knowledge. Not just stories.

But a flame.

A way of seeing.

A way of being in a world that no longer seemed to care.

Spring arrived quiet and late that year.

The kind of spring where snow still lingers in the corners of the yard, stubborn as memory. But inside the shop, things were different. The light came in warmer now. The air carried a kind of softness I hadn’t felt in years.

And Eli — he’d carved his first real piece.

It wasn’t perfect. The lines were crooked, the shaping uneven. But it was a small wooden bird, perched on a branch, head tilted skyward.

He held it out to me, eyes wide, unsure.

I turned it over in my hands. “What do you think it is?” I asked him.

He shrugged. “I think it’s trying to fly.”

I looked at him then — really looked — and saw something I hadn’t expected.

Hope.

That summer, the town fair came through.

They set up booths and stalls like they always did — funnel cakes, cheap toys, and loud music. I hadn’t gone in years. But Eli insisted we enter something together in the “heritage crafts” tent.

So we did.

We didn’t win.

But people stopped at our table. Not for the carvings, really — though they admired them — but for Daisy. For the way she sat there, carved from red oak, still as stone but somehow present.

One little girl touched her nose and said, “She sees me.”

And I swear, for a moment, I almost believed her.

Back in the shop, I carved a small plaque.

I nailed it just above Daisy’s wooden ears.

She watched with love. So must we.

Eli stood beside me when I hung it.

“That’s what you taught me,” he said. “More than chisels or sanding.”

I nodded. “It’s what she taught me too.”

These days, I don’t carve much. My hands get tired. My knees don’t like the stairs. But the shop still sings with the sound of wood and boyish laughter.

Eli comes every week. Sometimes alone, sometimes with a friend he’s teaching. The tools are in his care now. The bench, too.

And Daisy? She stays where she’s always been — on the old table by the window. Watching.

Listening.

One evening, as the sun dipped behind the trees and the golden light poured through the slats like honey, I stepped outside the house and looked toward the shop.

The windows glowed.

Inside, Eli stood hunched over the workbench. Focused. Careful. And just behind him, bathed in orange light, was Daisy. Her wooden eyes catching the sunset, as if looking toward something I couldn’t see.

I didn’t go in.

I didn’t need to.

I just stood there on the porch, one hand on the railing, and whispered, “She’s in good hands now.”

And for the first time in a long while, I didn’t feel like the world had moved on without me.

Because part of me — the best part — was still there.

In the hands of a boy.

In the eyes of a dog carved from love.

And in the quiet hum of a workshop that still remembered how to listen.