Part 1 – The Last Ride

On the morning Earl Walker signed the paper to end his old dog’s pain, he did something nobody expected him to do again. He wiped down his hunting rifle, tightened Duke’s faded collar, and turned his truck away from the vet and straight toward the pines.

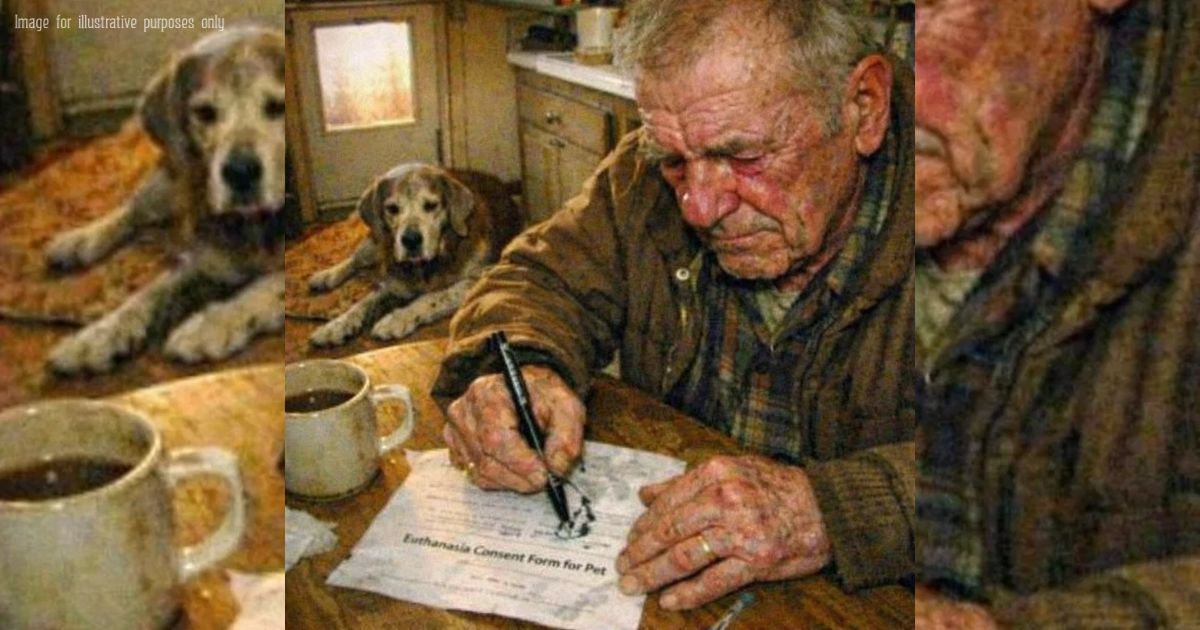

The kitchen was too quiet for a house that had held a dog for thirteen years. Earl stood at the table, glasses low on his nose, staring at the single sheet of paper from the vet’s office, the one with the polite words that meant “it’s time.” His hand shook just enough to make the ink smear when he signed his name. Duke lay on the faded rug by the back door, chest rising in shallow, raspy waves, eyes never leaving Earl’s face.

Earl capped the pen like it might explode if he dropped it and set the paper back in its envelope. His fingers went automatically to the coffee mug waiting on the counter, now stone cold. He drank it anyway, grimacing, feeling the burn travel down a throat that had shouted orders in factories and in the woods but almost never said “I’m scared.” Today, the word sat heavy behind his teeth.

By the back door, Duke tried to push himself up and failed the first time. His hind legs slipped on the rug, joints stiff with the kind of ache that medicine could only dull for so long. Earl walked over, crouched slow so his own knees wouldn’t protest too loud, and slid an arm under the dog’s chest. “Easy, soldier,” he muttered, the old nickname slipping out like a habit he’d never broken. Duke’s tail thumped once, soft as a tired heartbeat.

The worse nights came back in a rush, the ones when Duke paced the hallway until his paws trembled, when he lay panting beside Earl’s bed, trying to hide his whimpers in the mattress. Earl had sat awake in the dark, hand on warm fur, counting the seconds between each sharp breath. No animal that had given that much, he told himself, deserved to be trapped in a body that betrays it. That was what this appointment was: mercy, not punishment. That was what he kept saying, anyway.

On the wall by the back door hung Duke’s old orange collar, teeth marks still visible from his puppy days. Next to it rested the leash they rarely needed in the woods and, beside that, a rack with Earl’s hunting rifle, cleaned so many times it held more memory than metal. For years people had whispered that the Walker man finally hung up his gun, said the world didn’t need old hunters anymore. Earl had let them talk. The woods didn’t care what people said.

He hesitated only a second before taking the rifle down. There was dust on the stock, but the weight in his hands felt familiar, almost comforting. He checked the chamber out of habit and slid the safety on, then slipped it into the worn case. He wasn’t planning to shoot anything today. But walking into that forest without the rifle would feel like walking out of his own skin. Duke watched the whole ritual with tired curiosity, ears twitching at the soft click of metal.

Outside, the air had that late-autumn bite that smelled like wet leaves and distant wood smoke. Earl lifted Duke into the cab of the old pickup, grunting a little as the dog’s weight settled against his chest. There had been a time when Duke leapt into the truck bed on his own, barking at the door for Earl to hurry up. Now the dog leaned into him like a child too proud to ask to be carried. Earl kissed the white patch on Duke’s muzzle before he caught himself and pulled back, embarrassed by a tenderness no one was there to see.

The town slid past the windows in slow frames: the shuttered factory, the diner with half its neon letters burned out, the church sign begging in plastic letters for people to come back this Sunday. Men his age sat outside the hardware store on folding chairs, heads bent over coffee and old arguments. They raised two fingers in a lazy salute when Earl drove by, and he answered with the same small nod he’d been giving them since high school. None of them knew what the paper on his passenger seat meant. None of them knew he’d already said goodbye twice in his head before leaving the driveway.

At the edge of town, the blacktop split. To the left, the road wound down toward the strip mall and the vet’s office tucked between a laundromat and a nail salon. To the right, the pavement gave up and turned into a narrow dirt road, swallowed quick by pine and shadow. Earl’s hands tightened on the steering wheel as the turn signal ticked in the silence between him and Duke’s labored breaths. Left was what he’d promised the vet. Right was what he’d promised himself he was done with.

For a long moment, the truck rolled straight, engine humming like it didn’t care either way. Duke shifted, pressing his gray muzzle against Earl’s shoulder, letting out a low, almost apologetic whine. Earl could smell the dog’s fur, that mix of earth and sun and something like old rain. It hit him harder than any sermon. “All right,” he said, more to the windshield than to the dog. “One more walk, then.”

He flicked the turn signal to the right and eased the truck onto the dirt road. Gravel crunched under the tires, the sound echoing in the narrow tunnel of trees. The farther they went, the more the town disappeared behind them, swallowed by the tall pines that had watched Earl grow up, grow old, and grow quiet. Patches of light fell through the branches, striping Duke’s fur in bright and shadow as he watched the world outside with cloudy eyes that still seemed to know the way.

At the clearing, Earl killed the engine and sat for a second, listening to the sudden rush of silence. No traffic, no talk radio, just wind moving through needles and the far-off call of a bird he couldn’t quite place anymore. He slid out of the truck, joints popping, then opened Duke’s door. “Come on, old man,” he said. “Smell it while you can.”

Duke stepped down awkwardly, back legs shaking with the effort, but once his paws hit the damp earth, something in him woke up. He lowered his nose, inhaling deeply, tail giving a slow, uncertain wag. The dog moved forward, not fast, but with purpose, as if following a trail only he could see. Earl slung the cased rifle over his shoulder and followed, boots sinking into the soft ground that had held a thousand of their tracks before this.

They walked deeper into the trees, not saying anything. Earl didn’t have the words, and Duke never needed them. The air smelled of pine sap and old storms, the kind of smell that could drag a man backward through years without asking permission. Earl saw flashes of the past in every broken branch: Duke splashing through a creek, Duke disappearing into tall grass, Duke freezing mid-step to point at a deer that seemed carved from light.

Now, with twelve pounds of white hair frosting his muzzle and a limp in every step, Duke should have looked nothing like that young dog. But twenty minutes into the woods, with no town noise left at their backs, Duke suddenly stopped. His body stiffened from nose to tail, front paw lifting just off the ground, head angled toward the thick brush ahead. It was the old stance, the one Earl had seen him hold a hundred times, only this time it came with a full-body tremble.

Earl frowned and shaded his eyes, peering in the same direction. At first he saw nothing but a tangle of green and brown, the usual scatter of branches and shadow. Then, somewhere beyond the undergrowth, he thought he heard it—a sound that did not belong to wind or bird or deer. It was small and thin and human, like a sob swallowed too fast or a voice trying not to be heard at all. He felt Duke’s muscles quiver under his hand as the dog leaned forward, pointing deeper into the trees, as if the forest itself was holding its breath to see what Earl would do next.

Part 2 – The Cry in the Pines

Earl held Duke’s collar and listened, breath snagged in his chest. The sound came again, softer this time, like somebody trying not to cry. It floated through the trees in a shaky little wave that did not care he had an appointment with goodbye waiting on a printed sheet of paper back in town.

“Stay,” he whispered, even though he knew Duke would do no such thing.

The dog pulled forward, the old pointing stance trembling beneath worn-out muscles, nose aimed at the tangle of brush ahead. Earl followed, rifle case bumping against his back as he pushed aside branches that scratched his hands like they resented him for taking so long to come back. He moved slower than he used to, but the sound on the other side of the thicket stripped ten years off his knees.

The sob came again. This time he heard a word in it.

“Mom?”

Earl’s heart lurched. That was not the forest talking.

He shoved through the last curtain of leaves and almost tripped over the small backpack lying crooked in the dirt. Bright blue, with a patch half peeled off one strap. A few feet away, curled against the trunk of a pine, sat a boy. His dark hair stuck to his forehead, his cheeks streaked with dried tear lines and dirt. He clutched his knees like they were the only thing keeping him from falling apart.

When he saw Earl, he flinched hard enough to rasp his back against the bark. Duke, though, moved in slow, gentle arcs, tail wagging low, head tilted.

“Easy,” Earl said, palms open, voice softer than he knew it could be. “We’re not here to scare you, son. We heard you.”

The boy stared at Duke first. Kids always did. There was something about a dog that could cross distances no adult voice could. Duke stepped closer, hips wobbling, and rested his gray muzzle on the boy’s knee. The boy’s hand came up like it weighed more than his whole arm, then buried itself in the fur behind Duke’s ear.

“I… I don’t know where the trail went,” the boy whispered. “We were hiking with my uncle and I stopped to tie my shoe and then…” His sentence dissolved into a hiccup.

“How long you been out here?” Earl asked.

The boy blinked, trying to count hours he didn’t have a watch for. “Since… this morning? I don’t know. My phone died. I yelled until my throat hurt and then…” He swallowed. “I thought maybe a bear was going to come instead of my mom.”

“No bears today,” Earl said. “You picked the right dog to find you.”

He crouched, knees complaining, and studied the kid’s face. Pale around the lips. Eyes a little unfocused. Not broken, though. Not bleeding. Just scared and tired in the way only lost people get. Earl felt something unclench in his chest that had nothing to do with the paper in his truck.

“What’s your name?”

“Noah,” the boy said. His fingers tightened in Duke’s fur. “Is he… is he old?”

“Old as bad coffee and stubborn men,” Earl said. “This is Duke.”

Noah gave a shaky little laugh, the sound surprising both of them. Duke leaned more of his weight against the boy’s leg, as if offering himself as something solid to lean on. Earl reached into his jacket for his phone, the cheap thing one of his neighbors had bullied him into buying “for emergencies.” If this wasn’t one, nothing was.

The signal bars blinked in and out like they were thinking about it. He walked a few steps one way, then back, holding the phone up until he caught enough to make a call.

“Emergency services,” the woman on the other end said, voice calm and distant. “What’s your location?”

“In the north pines, off County Road Twelve,” Earl said. “Got a boy out here, seems lost. Name’s Noah. He’s breathing, talking, but he’s been here a while.”

They asked him questions about landmarks, about how far from the road, about Noah’s condition. Earl answered as best he could, keeping his voice even so the boy wouldn’t hear the worry underneath. When he hung up, he pocketed the phone and looked back at them.

“They’re coming,” he said. “Might take a bit. You hungry?”

Noah hesitated, then nodded.

Earl dug in his bag for the sandwich he’d stuffed there without thinking before he left the house. He broke it clean in half and handed a piece to the boy, the other to Duke. The dog sniffed it like he was insulted by the portion size, then ate it anyway, slow and thoughtful.

They waited in a broken-ring of silence and small noises. Noah’s chewing. Duke’s labored breathing. The wind shifting above them. Every now and then, the boy would glance toward the woods, like he expected them to close in. Each time, Duke nudged his arm back toward the safe circle of fur and flannel.

“Are you a hunter?” Noah asked suddenly.

Earl looked down at the rifle case resting by his boot. “Used to be,” he said. “Mostly we just walk now.”

“My mom says hunting is mean,” Noah murmured, a tentative challenge in his voice.

“Sometimes it is,” Earl said. “Sometimes it’s putting food in the freezer so you don’t have to decide which bill not to pay that month. Life’s funny like that.”

The boy seemed to roll that around in his head, not quite ready to let it go, not quite sure what to do with it. He shifted, and Duke grunted but did not move away.

The distant whup-whup of a helicopter blade cut through the trees as abruptly as a door slamming. Then sirens, muted by distance but growing. Noah’s eyes filled with fresh tears, a mix of relief and leftover fear. Earl placed a hand on his shoulder.

“That’ll be them,” he said. “You did the right thing, staying put when you got too turned around. The woods like to trick folks who think they can outrun them.”

Minutes later, voices called his name from the direction of the road. Earl stood, joints complaining, and whistled sharp through his teeth. Duke’s ears flicked, but he kept his head on Noah’s leg until the first bright-clad rescuer stepped through the trees.

“There you are,” the young woman said, relief unclenching the line of her shoulders. “We’ve been combing the trails all afternoon.”

She knelt by Noah, checked his pulse, asked him questions he could finally answer without shaking. Another rescuer appeared, then a third, radio crackling with clipped words. Somebody handed Noah a bottle of water and a blanket that smelled faintly of storage.

The young woman glanced at Earl. “You the one who called it in?”

“Just followed the dog,” Earl said.

She looked at Duke, at his gray muzzle and the stiffness in his back legs, and her face softened in that way people have when they see something both noble and fragile. “Well, thank you, Duke,” she said, reaching out to scratch his head.

Without really thinking, she pulled her phone from her pocket and snapped a quick picture. The old man, the old dog, the boy with blanket-wrapped shoulders leaning against both like they were a wall that could not crumble.

“We’ll walk you back to the road,” another rescuer said. “Ambulance is there, just to check him out. His mom is on her way. She about tore the dispatcher’s ear off when they told her he was found.”

They moved as a slow, careful group. Noah refused to let go of Duke, so they adjusted their pace to the dog’s shuffle. The rescuers talked softly into their radios, using a language of codes and numbers Earl didn’t bother translating.

At the tree line, the forest cracked open into the narrow dirt pull-off where Earl had left his truck. A small ambulance idled nearby, lights off but ready. A sheriff’s SUV sat behind it. Two deputies stood outside, hands on belts, relief plain on their faces when they saw Noah.

“Your mom’s five minutes out,” one of them said gently. “You did good, buddy.”

They shepherded the boy toward the open ambulance doors. Noah looked back over his shoulder, eyes searching for Duke. Earl gave the leash a little slack, and Duke stepped forward enough for Noah’s fingers to sink once more into his fur.

“Thank you,” Noah whispered.

Earl answered before the dog could. “He was going to walk today anyway,” he said. “Might as well make himself useful.”

A few minutes later, as the paramedic checked Noah’s vitals and the deputies finished their notes, the young rescuer who had taken the photo stood by her SUV, thumb moving fast over her phone.

“Just posting something for the station’s page,” she told her partner. “People need good news once in a while.”

The caption wrote itself in her head as her fingers tapped: Old dog on his ‘last walk’ helps save lost boy in the pines. She added a couple of soft-hearted emojis, hit “post,” and didn’t think about it again.

Earl did not see any of that. He was at his truck, one hand braced on the door, the other resting on Duke’s back, feeling the steady thump of a heart that had given him every forest season for over a decade. He pulled the crumpled appointment reminder from his pocket, stared at the time printed in neat black numbers.

They were already late.

He reached for his phone again and called the vet’s office.

“I’m sorry,” he said when the receptionist answered. “Something came up in the woods. We’re running behind.”

There was a pause on the other end, then a gentle reply. “It’s all right, Mr. Walker. We can move you to a later slot today, or another day if you need. Just let us know what feels right.”

He hung up and slid the phone back into his pocket, staring at his reflection in the truck window. Beside him, Duke slowly lowered himself to lie in the shade, breathing hard but not complaining. From the road, the rising wail of another siren announced Noah’s mother long before her car appeared.

Somewhere in town, and then far beyond it, screens began to light up with the picture of an old dog in a shaft of pine-filtered light, a frightened boy clinging to his collar, and a weathered man kneeling beside them. People scrolled, paused, smiled, wiped their eyes, and tapped the small button that sent the image further into the world.

Earl Walker, standing in the dust by his truck with a dog who didn’t know he was a hero, had no idea that by the time he got back to his quiet house, half the county would be arguing about whether mercy meant letting go or holding on a little longer.

Part 3 – The Viral Old Hunter

Michael Walker saw the video in the most ordinary way possible. It showed up between a clip of a cooking hack and a coworker’s vacation slideshow while he was eating lunch at his desk, one earbud in, pretending to care about a spreadsheet.

The headline caught his eye first. Old Dog on ‘Last Walk’ Helps Save Lost Boy in the Pines.

He almost scrolled past it. The internet spat out new heartwarming stories every hour, perfectly calibrated to make people cry for thirty seconds and then buy something. But the still image made his thumb freeze above the glass.

An old man in a faded flannel shirt, hat brim low, knee dug into the forest floor. A boy wrapped in a gray blanket, face tucked into the neck of a white-muzzled dog. Pine needles, afternoon light, the kind of picture people printed and stuck on refrigerators until the tape yellowed.

Michael zoomed in, even though he already knew.

“Come on,” he whispered to the screen. “No way.”

But it was.

The angle wasn’t perfect, the resolution grainy, but he’d grown up with that shape in the doorway, that slope of shoulders, that stubborn jawline. He knew the way his father’s hands wrapped around a leash like it was both a lifeline and an obligation.

It was Earl.

And Duke, though the dog in the video looked like a ghost of the one in his childhood memories. Back then, Duke had been all muscle and wild joy, streaking through the yard like a bullet made of sunshine and dirt. The dog on his phone screen lay heavy, each breath visible, eyes cloudy but still somehow sharper than half the humans in the comments.

Michael clicked the volume up.

The video was short, just under a minute. A shaky walk toward the trio. A few phrases from the rescuers. A close-up of Noah’s tear-streaked face pressed into Duke’s fur. At the end, the young woman filming whispered, “Good boy,” and the clip cut off.

Below, the comment section crawled like an overturned ant hill.

I’m crying at my desk, thanks.

That dog is a better person than half my exes.

Wait, why is it his ‘last walk’? Someone explain.

Halfway down, someone pasted a screenshot of a second post, this time from a local community group Michael didn’t follow. A woman’s frantic message from hours earlier, begging for help finding her nephew lost on the trail. Under that, an update: He’s been found. An older gentleman and his dog heard him crying. We are so grateful.

There were new comments since then.

I heard the dog is really sick and they were on their way to put him down when they found the kid.

No way. You can’t put that hero down now. That’s wrong.

It’s not wrong if he’s in pain. Sometimes the kindest thing is the hardest one.

Michael leaned back, phone still in his hand, the hum of the office fading into static. He hadn’t been home in almost a year. The last time, he and his father had barely spoken without something sharp in it. There were a hundred texts he hadn’t answered, a dozen calls he’d ignored until they stopped coming. The guilt sat in his chest like a stone he’d learned to work around.

He never imagined the thing that would punch through that stone would be a sixty-second video on a stranger’s feed.

“Hey, you okay, man?” his coworker asked from the next cubicle, noticing his stillness.

“Yeah,” Michael said automatically. “Just… I know that guy.”

“The old dude with the dog?”

“Yeah,” Michael said. “That’s my dad.”

The coworker whistled softly. “Your dad’s internet famous now. Lucky you.”

Lucky. That was one word for it.

Michael muted his notifications as they started pinging. Old high school classmates, a cousin he barely spoke to, even his ex-wife—people tagged him, messaged him, forwarded the link. Is this your dad? This looks like Earl, right? Dude, your old man is a legend.

He scrolled through more comments, jaw tightening.

Someone needs to stop that vet. That dog earned the right to live out whatever time he’s got left.

People spend thousands on dogs while kids can’t afford school lunch. World’s upside down.

Don’t drag politics into this, just let the dog have his moment.

Beneath it all, the video’s view count ticked up like a slow heartbeat.

Michael didn’t know how sick Duke was. He hadn’t been there to see the slow limp grow worse, the nights when the dog paced because lying down hurt, the mornings when he struggled to stand. He had only one image: his dad, hat low, dog at his heel, a line of orange in the distance where a deer once stood. And that other one, burned deeper: a deer that didn’t fall right away, its legs folding wrong, its breath harsh and panicked until his father did what had to be done.

He pushed that memory away, but it clanged around in the back of his mind like loose hardware.

The office noise came roaring back all at once: printers, phones, someone laughing at a joke posted in the team chat. Michael’s screen saver slid across his computer, a cheerful mountain landscape trying to sell him on a vacation package. He stared at it without really seeing it.

Then he opened his email and fired off a quick message to his supervisor.

Family emergency. I need to take a couple of days. I’ll log back on remotely if I can.

He didn’t wait for a reply. He grabbed his jacket, his keys, and his charger. At the elevator, his phone buzzed with an unknown number. He almost let it ring out. Almost.

“Hello?”

“Is this Michael Walker?” The voice was female, professional, slightly wary.

“Yeah.”

“This is Dr. Alvarez’s office. Your father listed you as an emergency contact on his file. I hope you don’t mind me reaching out.”

His stomach dropped. “Is he okay?”

“Oh, he’s fine,” she said quickly. “Far as we know. I’m actually calling about Duke. We had an appointment scheduled today… it looks like they ran late. He called to push it back, but I wanted to let someone in the family know that his condition has been getting worse. I can see that online things…” She hesitated, choosing her words. “Might be getting noisy. I just want you all to have the medical information you need.”

Michael pinched the bridge of his nose. “So you think it’s time?”

“There’s no clock on kindness,” she said. “But the pain is real, and it’s getting harder to manage. These decisions are for you and your father to make, not strangers on the internet. I wanted to say that out loud, just once, before the opinions drown everything else.”

He swallowed. “Thank you.”

“If he wants to come in tomorrow, we’ll be ready. If he wants to wait a bit, we can work on pain control. He’s earned our patience.”

Michael ended the call with a promise he hadn’t planned on making. “I’ll be there,” he said.

The highway out of the city was a gray ribbon flanked by billboards and tired trees. As he drove, he fought the urge to check his phone at every red light. Somewhere between one exit and the next, he let the car drift onto the shoulder, put it in park, and pulled out his phone again.

The video had passed half a million views. Someone had turned Duke into a sketch and posted it. Someone else had written a short poem. Another person had started a fundraiser “to help the old hero dog get all the care he needs.” The total was already climbing higher than Michael’s yearly salary when he first left town.

In the comments, people argued like they were on trial.

If you put that dog down, you’re a monster.

You don’t love animals more than their owners do. You just love your own opinion.

My grandma had to say goodbye to her dog last year, and it broke her, but watching him suffer would’ve been worse.

Michael tossed the phone onto the passenger seat like it had burned his hand. Duke’s picture still glowed up from the glass, eyes soft, boy’s fingers tangled in fur.

He put the car back in gear and merged onto the road that would take him home.

Behind him, in offices and bedrooms and coffee shops across the country, people who had never heard of Earl Walker yesterday shared his story over lunch and late-night scrolling. They cried over a dog they would never meet and drafted furious, tender paragraphs about what mercy meant to them.

Up ahead, in a quiet house at the edge of town, Earl Walker refilled Duke’s water bowl and had no idea that the next time he stepped into the grocery store, strangers would look at him like they knew his heart better than he did.

Part 4 – Heroes for a Day

The folding chairs in the community center creaked under the weight of neighbors and relatives and people who’d just come because they’d seen the video and wanted to be near something that made them feel less tired inside.

A banner printed on thin vinyl hung crooked at the front of the room. Thank You, Duke and Mr. Walker, it read in cheerful blue letters, the font slightly too playful for Earl’s taste. Under it stood a podium with a borrowed microphone, a table with a plastic tablecloth, and an arrangement of supermarket flowers that tried their best.

Earl shifted his weight from one foot to the other, the unfamiliar cotton of a clean shirt rubbing against his neck. He’d let the woman from the town office talk him into coming. “Just a little ceremony,” she’d said. “No speeches if you don’t want them. Noah and his family want to say thank you.”

Duke lay at his feet on a borrowed dog bed, sides rising and falling slower than they used to. Someone had tied a red bandanna loosely around his neck, the fabric bright against his pale fur. He accepted the fuss with the weary dignity of a retiree dragged out to one last staff party.

“You sure about this?” Earl muttered down to him.

Duke thumped his tail once, as if to say that for a man who’d always told him to heel, Earl was awful bad at sitting still and letting people be kind.

The room hummed with low conversation. A camera from the local news station sat on a tripod in the third row, its red light off for the moment. A woman with a tablet moved near the back, snapping photos for the town website.

The double doors opened again, and Noah walked in between his mother and uncle. His scraped knees peeked out below his shorts, bandages bright against his skin. He hesitated when he saw all the faces, then spotted Duke and made a beeline straight for him.

“Hi, buddy,” Noah said, dropping to his knees beside the dog. Duke’s tail picked up some speed, and he lifted his head enough to lick the boy’s fingers. The room made a soft collective sound, half laugh, half sigh.

Noah’s mother approached Earl with eyes that had clearly run out of sleep before they ran out of tears. She extended her hand, squeezing his with both of hers.

“I don’t know how to say thank you,” she said. “I’ve tried all the words, and none of them feel like enough.”

“You don’t have to,” Earl replied. “He’s the one who heard him.”

“You’re the one who followed,” she said. “You both brought my boy home.”

The town clerk tapped the microphone, and the small feedback squeal made everyone jump. “If we can all find a seat,” she said, smiling in that practiced way of people used to coaxing crowds. “We’ll get started.”

They settled. Earl remained standing off to the side, one hand on Duke’s collar, ready to bolt if the attention started to feel like interrogation.

The clerk spoke first, saying all the words people say in these situations: about community, about courage, about being there for one another when it counts. The pastor from the local church offered a short blessing, thanking “our Creator for putting this good dog and this good man in the right place at the right time.”

Then it was Noah’s turn.

He shuffled up to the microphone, blanket-free now but still clutching something for comfort: a worn tennis ball someone had given him for Duke. He stared at the crowd for a second, then focused on the dog instead.

“I got lost,” he said, voice small but clear. “And I was really scared. I thought something bad was going to happen. I yelled and yelled. Then I heard branches and I got more scared because I thought maybe it was a bear or something.”

A ripple of gentle laughter swept the room and made it easier for him to continue.

“But it wasn’t a bear,” Noah said. “It was Duke. He’s old, but he still came.” His voice cracked on the last word. He knelt to place the tennis ball gently by Duke’s paw. “He’s my hero.”

The applause rose, honest and a little messy, not the crisp kind from televised award shows. People wiped their eyes with the backs of their hands, with tissue, with shirt sleeves.

The local news reporter took over then, microphone in hand, camera light clicking on. She kept it respectful, touching on the feel-good beats.

“Mr. Walker, would you like to say a few words?” she asked.

He shook his head once. “I do better in the woods,” he said into the mic when she held it out anyway. “I’m no good at speeches.”

She didn’t push. “Maybe just tell us what Duke means to you?”

He glanced down at the dog, then at the room. A hundred eyes waited for him to perform some neat, quotable gratitude.

“He’s… been with me a long time,” Earl said. “He’s dragged me out of more bad spots than I care to admit. He’s a good dog.”

“Are you going to keep him around now?” someone called from the back, half-joking, half-deadly serious. “Can’t put down a hero, right?”

The air tightened.

The reporter shifted, sensing a story sharp enough to cut her cozy segment. “There has been some conversation online,” she said carefully, “about Duke’s health, and what comes next. Do you have anything you’d like to say about that?”

Earl’s grip on the collar tightened.

“My dog is old and he hurts,” he said, choosing each word like it weighed more than it used to. “We’re talking with the vet about what’s best for him. That’s between us, not between me and…” He gestured vaguely outward, toward the invisible reach of the internet. “All that.”

“But he just saved a child’s life,” another voice chimed in. “Doesn’t that change things?”

Someone near the front turned around, frowning. “You don’t know what pain that dog feels at night. Don’t guilt a man who’s trying to do right.”

The room fractured into low murmurs. Pro-keep-him voices, pro-let-him-rest voices, people trying to hush everyone back to polite appreciation. Duke, catching the tension through his leash, lifted his head and gave a small confused whine.

Noah slid closer and laid both hands on the dog’s side, as if anchoring him to the calm center of the storm.

The reporter pulled back, senses finally recognizing a line she shouldn’t cross on local afternoon TV. “What matters is that today we are grateful,” she said, smile back in place. “Whatever decisions come later, this community is behind you.”

Her words were smooth, but they didn’t erase the sting of the questions. Earl felt exposed, like someone had taken his most private fear and pinned it up on the bulletin board for strangers to comment on.

As the event wound down, people filtered forward in ones and twos to say their personal thank-yous. Some touched his arm, some only Duke’s fur. A few pressed folded bills into his hand “for food” until he gently refused any more. Someone mentioned a fundraiser they’d seen online, money collected for Duke’s vet care and for fixing the sagging roof on Earl’s porch.

“You’re famous now,” one man joked. “Our own hero of the pines.”

Earl shrugged. “I’m still the same old man who forgets trash day,” he said.

He was bending to help Duke to his feet when the air shifted. It wasn’t anything he heard so much as something he felt, like the moment before a storm when the wind changes direction. The hairs on his arms stood up.

He looked toward the doors and saw his son.

Michael stood there in his city jacket and worn jeans, holding himself like someone who wasn’t sure if he was invited or about to be asked to leave. The years had put faint lines around his eyes that hadn’t been there the last time Earl really looked.

For a heartbeat, the room blurred at the edges. Earl could hear his own pulse louder than the leftover chatter.

Michael’s gaze dropped to Duke, softened, then rose to meet his father’s.

“You look the same,” Earl said, because it was easier than saying I didn’t expect you.

“You don’t,” Michael answered, because it was easier than saying I’ve missed you.

Someone, reading the room, started stacking chairs in the back, giving them the illusion of privacy. Noah’s mother guided her son toward the snack table, whispering something about cookies. The reporter’s camera light finally clicked off.

“Hi, Duke,” Michael said, crouching. The dog sniffed his hand, then licked it, memory bridged in one wet swipe. “Still stealing the show, huh?”

“Always,” Earl said.

They stood in awkward silence for a few seconds, the weight of all the unsaid years pressing down.

“I saw the video,” Michael blurted finally. “I saw… all of it. People are losing their minds over you.”

“Over him,” Earl corrected. “I’m just the guy holding the leash.”

Michael’s jaw tightened. “They also know about the appointment, Dad. People are saying if you go through with it, you’re…” He stopped himself, but the unfinished accusations hung there anyway.

Earl straightened, shoulders squaring. “People are saying a lot of things about a dog they’ve never sat up with at three a.m. while he cried,” he said. “And about a man they don’t know.”

“I know you,” Michael said, voice sharper than he meant. “I know what you’re capable of when there’s a gun in your hand and something breathing at the other end.”

The words hit harder than either of them expected. A few heads turned. Duke whined again, a thin, confused sound.

Earl’s stare went cold. “So that’s what you came to say?”

Michael swallowed, color rising in his face. “I came to make sure you’re not about to do the same thing to him you did to…” His voice dropped. “To that deer. To every animal you ever decided had lived long enough.”

Conversations around them faltered, then died. The room stretched thin and sharp as glass.

For a long second, Earl didn’t speak. His hand on Duke’s collar was steady, but Michael could see the small tremor in his fingers.

When he finally answered, his voice was quiet enough that the room had to lean in.

“You think putting a bullet in a deer’s heart so it doesn’t stagger and choke for an hour is the same as dragging out the pain of a dog who can’t even climb three steps without crying?” he asked. “You think mercy is just another word for cowardice, is that it?”

Michael’s mouth opened, then closed.

Outside, a car door slammed. A baby cried somewhere down the hall. Inside the community center, nobody moved.

Duke shifted between them, old body wedged like a living question mark.

“Tell me something, son,” Earl said, eyes never leaving Michael’s. “If you’re so sure I’m wrong, why did it take the whole internet to drag you back here?”

Michael flinched like he’d been slapped. The sting of truth burned worse than any insult.

He turned away, heading for the side door, jaw clenched. Behind him, he heard Duke try to stand, paws scrabbling on the smooth floor. Earl’s “Easy, boy” chased him out into the bright afternoon.

The sunlight outside was harsher than he remembered, bouncing off car hoods and the community center’s peeling paint. Michael walked to the end of the lot, then stopped, breath shaking. He’d come to fix something. All he’d done so far was break it further.

Inside, Earl watched the door close behind his son. For a moment, he felt ninety years old and made of nothing but mistakes. He bent to pick up Duke’s leash, and the room tilted, just a fraction. A pinprick of pain blossomed behind his breastbone, sharp enough to make him grab the edge of a chair.

Duke whined, nose bumping against his leg, eyes wide.

“I’m fine,” Earl muttered, waiting for the world to steady. “Just stood up too fast.”

But Duke didn’t move away. He stayed pressed against Earl’s knee, as if he’d caught the scent of something his owner wasn’t ready to name.

Part 5 – Old Wounds

The house felt smaller with two people in it, even though it had been built for more once.

Michael stood in the kitchen doorway, watching his father move slowly from counter to table. The ceremony had ended, pictures taken, hands shaken. The town clerk had pressed leftover cookies and a disposable tray of sandwiches into Earl’s arms “so you don’t have to cook tonight.”

They’d driven home in near silence, Duke curled in the back seat, the town’s eyes still buzzing at the back of Earl’s head. Now, the late afternoon light slanted through the thin curtains, turning dust motes into floating ghosts.

“You should sit down,” Michael said finally. “You went pale back there.”

“I’m standing in my own kitchen, not running a marathon,” Earl replied, setting a jar of pickles on the table like it weighed nothing. His hand lingered a second longer than it needed to on the chair back, though.

Michael saw it. He also saw the pill bottle by the sink, its white label worn from use.

“How long has your chest been hurting?” he asked.

Earl stiffened. “Doctor says it’s just reminders that I’m not thirty anymore.”

“The doctor gave it a name?”

“Don’t remember it,” Earl said, too fast. “She gave me pills. I take them. End of story.”

Michael stepped into the room, palms up. “Maybe it’s not the end of the story, Dad. Maybe you shouldn’t be carrying him up and down steps anymore. Or chopping your own firewood. Or pretending that you can haul the whole world by yourself until something breaks.”

Earl’s jaw clenched. “A man who lets other people do all his lifting forgets how to stand.”

“A man who refuses help dies alone on his kitchen floor,” Michael shot back, sharper than he meant. “Is that what you want? For someone to find you three days later because the mail piled up?”

Silence slapped between them. Duke, lying on his bed in the corner, lifted his head, ears twitching.

Michael dragged a hand over his face. “Look, I’m not trying to fight,” he said, softer. “I just… I saw you grab that chair today. That scared me.”

“What scared you when you were a boy was different,” Earl replied. “Back then, it was me holding a rifle and a deer still breathing.”

Michael flinched. “You remember that.”

“I remember it all,” Earl said. His eyes went far away, into woods that weren’t on any map. “You were twelve. Thought you were ready. First season you begged to come. I said yes because I thought… I don’t know. Maybe I thought I could hand you this life like I hand someone a wrench.”

He sank slowly into the chair, the fight leaving his shoulders.

“You remember what I remember,” Michael said. “Hurting something and watching it suffer while you stood there and called it part of the process.”

“I remember hitting too far back on a cold morning,” Earl said. “My hands numb, my breath fogging the scope. I remember watching that deer stagger and knowing I’d failed it.” His voice roughened. “So I did what had to be done and made it quick.”

“You made me watch,” Michael whispered.

“You were already watching,” Earl said. “I didn’t drag your head around. You wanted to see what this life really was, not the glossy pictures in magazines. I thought if you saw it all, you’d understand that hunting was more than bragging at the diner.”

“What I understood,” Michael said, “was that your mercy looked like violence. That you could decide when something’s life was done and nobody could tell you no.”

Earl stared at the knot in the wooden table, thumb rubbing it like he could smooth out the years.

“You think I liked it?” he asked quietly. “You think I walked back to the truck whistling? I couldn’t feel my feet for the rest of the day. But that deer would have died slower if I’d walked away.”

Michael opened his mouth, then shut it. The memory was sharp and jagged, but under it, there had always been a thread of something he’d never named: his father’s tight jaw, his silence on the drive home, the way he’d cleaned the rifle that night like he was trying to erase something he couldn’t.

“I still don’t like guns,” Michael said finally. “Or hunting. Or that whole idea of proving you’re a man by what you can kill.”

“Fair enough,” Earl said. “World changed. Maybe it needed to.” He glanced toward Duke. “But Duke doesn’t care about manhood or debates. He cares about how much it hurts to stand up in the morning. And I’m the one who hears him at two a.m., not the folks typing paragraphs on their phones.”

Michael followed his gaze. The dog lay with his head on his paws, eyes half-closed, chest rising in slow, measured effort. A few years ago, he would have been under the table, begging for sandwich scraps, tail banging like a drum.

He remembered coming home for Christmas one year and seeing Duke jump once, twice, then hesitate, as if his legs had forgotten the third spring. He’d noticed, frowned, then let work emails pull him back out of town before he asked his father if he was worried.

Now, the missed questions weighed heavier than the old arguments.

“I’m sorry,” Michael said suddenly.

Earl looked up, surprised. “For what?”

“For leaving you to do all of this alone,” Michael said. “For letting one bad trip to the woods define every conversation we had after. For calling you a…” He swallowed the word. “For thinking I knew everything because I moved to a city and learned new vocabulary for pain and justice.”

Earl’s mouth twisted, somewhere between a smile and a grimace. “You were a kid who saw something ugly and decided to run in the opposite direction,” he said. “Can’t fault you for that. Everyone runs from something.”

“What did you run from?” Michael asked.

The question hung there. Earl’s eyes drifted to the sideboard where an old photograph sat in a cheap frame. A younger Earl, arm slung around another man’s shoulders, both of them grinning in blaze orange vests, Duke a blur of motion at their feet.

“Tom,” Michael said quietly. “You haven’t talked about him in years.”

“There’s a reason,” Earl replied. His fingers tightened on the edge of the table. “I don’t talk about that day because I hear it every time I close my eyes.”

Michael waited, sensing that if he pushed too hard, the door would slam shut again.

“I thought I had more time with him,” Earl said finally. “We were halfway through the trail. He’d been breathing a little heavy, but he always did. We joked about being old. He laughed, then he grabbed his chest and went down. I yelled into the trees for help, but the trees don’t answer. Duke ran circles, barking his head off. I tried to get a signal, but the phone just spun. By the time the rescue folks found us, they said I’d done what I could. Asked me if he had any heart problems I knew of.”

“Did he?” Michael asked.

Earl’s jaw clenched. “His wife told me later he’d skipped a couple of checkups. Didn’t want to be told to slow down. Didn’t want to be told he couldn’t go out there anymore.”

He took a slow breath.

“I’ve carried that day like a stone in my pocket ever since,” he said. “Every time Duke limped, every time my chest twinged, I heard that stupid joke we made about being old. I promised myself I wouldn’t let him die out there like Tom. Not choking on cold air, not waiting for help that might not come.”

Michael felt something shift inside, a plate of blame sliding off its old anchor.

“So when the vet said it might be time,” Earl continued, “I thought about nights Duke couldn’t lie down without crying. I thought about Tom staring up at me and asking if we almost made it. I thought about how mercy sometimes looks like walking away and sometimes looks like staying until the very last breath and making sure it’s not taken alone.”

He looked up, eyes glassy but hard.

“You think I’m eager to hand him over?” he asked. “You think this is easy?”

“No,” Michael said. His own throat tightened. “I think… I think I’ve been so busy hating the way you showed me mercy once that I didn’t see the ways you’ve been trying to use it now.”

They sat there, two men separated by years and a table and a thousand small misunderstandings, letting the words settle.

A sudden scrape interrupted them. Duke was trying to stand. His front legs pushed, his back legs followed a second too late. He wobbled, then his paws slid on the worn linoleum.

“Hey, hey,” Michael said, jumping up. “Easy, buddy.”

But Duke insisted, muscles quivering with the effort. He made it halfway up, then one hind leg buckled. His body tipped, colliding with the side of the table. The jar of pickles rattled. Earl lurched forward, a hand on the dog’s shoulder, the other grabbing the table to keep himself upright.

Pain shot across his chest like a lightning line. His vision narrowed.

“Dad?” Michael’s voice sounded far away.

Earl heard Duke whine, a high, thin sound that sliced through the fog. He tried to answer, to say it was nothing, that he just needed a minute. His knees disagreed.

The world tilted. The chair skidded. He felt himself falling and hated that he couldn’t fight it.

Strong hands caught his arm just before he hit the floor. Michael’s face swam above him, pale and terrified in a way that made him look twelve again.

“Dad, stay with me,” Michael said, fumbling for his phone with his free hand. “I’m calling an ambulance.”

Earl wanted to argue, to wave it off as a dizzy spell, but his chest felt squeezed in a fist. Duke pressed himself against Earl’s other side, eyes wide, breath coming faster in sympathy or alarm.

“I’m fine,” Earl tried to say, but the word came out as a breathless croak.

Michael didn’t listen. He had the phone to his ear, rattling off their address, the symptoms, the history. Outside, somewhere in the distance, sirens that had once signaled help for a lost boy now started to turn toward a tired, stubborn old man who’d spent his whole life pretending he didn’t need saving.

On the kitchen floor, between the table leg and a dog bed that suddenly seemed too far away, Earl felt Duke’s fur under his hand and his son’s grip on his arm. For the first time in a long time, he let himself admit the thing he’d been outrunning since the woods took his friend.

He could not carry this alone anymore.

Part 6 – The Heart and the Hound

The ceiling of the ambulance looked too close for a man who’d spent half his life under open sky. Earl lay on the narrow cot, the straps loose but present, making him feel more fragile than he liked. A paramedic with kind eyes asked him questions about his age, his medications, whether the pain was sharp or dull, constant or sneaking. He answered like he was filling out a job application, annoyed at every box he had to check that said he wasn’t invincible anymore.

At his side, Duke’s head rested on the edge of the cot, one paw hanging over, claws clicking against metal every time the vehicle bounced. Michael sat on the bench opposite, one hand on the dog’s shoulder, the other gripping the rail like the ride might throw him. His face was pale and tight, but there was a stubbornness in his jaw that looked very much like the man on the cot. The siren wasn’t screaming, just humming in that urgent, muffled way that said they were serious but not in a full-blown panic.

“Chest felt tight, you said?” the paramedic repeated, checking the monitor. “How long has that been going on?”

“Long enough that the doctor’s bored of hearing about it,” Earl muttered. “Couple months. Comes and goes like a nosy neighbor.”

Michael shot him a look. “You didn’t tell me it was that bad.”

“You didn’t ask,” Earl said, then immediately regretted the sharpness in it. He closed his eyes and forced his shoulders to loosen. “Didn’t want to make it your problem.”

The paramedic’s glance flicked briefly between father and son, reading more history in that exchange than either of them wanted to explain. “He did the right thing calling us,” she said to Michael. “Sometimes we get there in time because somebody stopped pretending they were fine.”

At the hospital, everything blurred into a rush of white and soft-sole shoes. They wheeled Earl into a room with too many machines and asked him to repeat his name, his birthday, his symptoms until the answers felt like a song he’d never liked but knew all the words to. They ran tests with names he didn’t catch, pasted sticky pads to his chest, slid him in and out of whirring tubes that smelled faintly of metal and antiseptic.

Through it all, Michael hovered near the doorway, forced to leave Duke with a volunteer by the entrance. The dog watched Earl disappear down the hallway with a look that made Michael’s chest ache. Every now and then, he heard Duke let out a short, uncertain bark, followed by the murmur of someone reassuring him.

A gray-haired doctor finally came in with a chart and a practiced half-smile meant to soothe. “Mr. Walker,” she said. “I’m Dr. Kemp. We’ve looked at your tests.”

“Let me guess,” Earl replied. “I’m not winning any marathons this year.”

Her smile twitched. “Your heart’s been working harder than it should. You’ve probably had these episodes for a while. They’re not big enough to be full-blown attacks, but they’re warnings. We can adjust your medications, set you up with follow-up care, but you need to take it seriously.”

“What does ‘seriously’ mean?” Michael asked, arms folded tight.

“It means less strain, more rest,” Dr. Kemp said. “It means no hauling heavy loads alone, no ignoring pain until you hit the floor. It might mean considering different living arrangements eventually. Being closer to care. Maybe closer to family.”

Her eyes slid deliberately toward Michael, then back to Earl.

“I’ve got a house,” Earl said. “I’ve got a dog who knows every inch of the yard. Uprooting all that doesn’t sound like rest to me.”

“Staying exactly the same while your body changes doesn’t always work either,” the doctor replied gently. “You don’t have to make decisions today. But pretending nothing’s different is not an option if you want more time.”

“More time for what?” Earl asked, and it came out more honest than he meant.

She hesitated, then shrugged. “More time for whatever you’re still here for,” she said. “More time to walk that dog, maybe. More time to argue with your son.”

Michael snorted softly, a laugh strangled halfway. “We’re very good at that part.”

They kept Earl for observation overnight. The room was small, the sheets too crisp, the air smelling like bleach and boiled vegetables from the cafeteria down the hall. Michael sat by the window in a plastic chair that squeaked when he shifted. His phone buzzed every few minutes on the tray table, but he ignored it until the buzzing became angry.

When he finally picked it up, he saw why.

The video had crossed a million views. The local news segment from the ceremony was now spliced together with the rescue footage, set to soft piano music. Comments flooded in faster than he could scroll. Someone had posted a link to a fundraiser titled “Help Duke the Hero Dog and His Owner Live Out Their Days in Comfort.”

He clicked, heart pounding. The goal was modest. The total raised had already tripled it. People from states he’d never visited had left notes along with their donations.

For Duke. For my grandpa’s old dog who helped raise me. Thank you.

My dad is stubborn like Mr. Walker. Use this to fix whatever he’s too proud to spend money on.

This is for the roof, the meds, and anything that brings that dog joy. Love from Ohio.

He rubbed his hand over his face, torn between gratitude and a rising, unsettled feeling in his gut.

“Everything all right over there?” Earl asked from the bed, eyes half-open.

“You’re… trending,” Michael said, because there wasn’t a better word. “People started a fundraiser for you and Duke. They want to fix your porch, pay for vet bills, send you on some kind of… retirement tour, I guess.”

Earl grunted. “I don’t need tourists in my yard.”

“That’s not what I mean,” Michael said. He turned the phone so his father could see the number climbing on the screen. “This could help, Dad. New meds for Duke. A ramp for the stairs. Maybe some help around the place.”

Earl squinted at the numbers like they were written in a language he didn’t trust. “That’s a lot of money for folks who don’t even know if I yell at the TV when the game’s on,” he said.

“They feel like they do,” Michael answered. “They saw you walking into the trees when you could’ve kept driving. They saw Duke stand between a scared kid and the forest. People want to believe that means something.”

“Meaning’s cheap when it comes with a ‘share’ button,” Earl replied. But there was no real bite in it, just a wary tiredness. “What are they going to say when they find out I might still have to let him go?”

Michael didn’t have an answer.

Later that evening, when the hospital hallway quieted and the TV in the room played a game show with the volume low, Michael stepped into the corridor to take a call. The number on the screen belonged to the vet clinic.

“Mr. Walker?” The voice was familiar. Dr. Alvarez. “I hope I’m not calling too late.”

“This is his son,” Michael said. “He’s here, but he’s resting. We had a bit of a scare.”

“I heard,” she said. “Small towns carry news like the wind. Is he all right?”

“They say he will be if he stops pretending he’s invincible,” Michael replied.

“That’s a tall order for a man his age,” she said softly. “Listen, I wanted to talk to you both about Duke. With everything that’s happening online, I’m worried the pressure around this decision is going to become unbearable.”

He leaned against the wall, the paint cool against his back. “He’s not going to let strangers decide for him,” Michael said. “But… I’m not sure he’s listening to his own body either.”

“Duke is in significant pain,” Dr. Alvarez said. “We can adjust his medication, and the fundraiser means we won’t have to cut corners. That’s a blessing. It also means we can talk realistically about hospice care—keeping him comfortable at home until… you decide it’s time. And if, at some point, you choose euthanasia, we can do it in a way that is gentle, familiar, and private.”

“Not in a bright room between a laundromat and a nail salon,” Michael said.

“Exactly,” she replied. “But that choice has to be about Duke, and about what your father can handle, not about what the loudest commenter thinks.”

Michael closed his eyes. He could picture Duke lying on his bed by the door, ears flicking toward every sound, too loyal to go first even when his body begged for it. He could picture his father beside him, shoulders hunched, hands hovering like he wanted to fix it and couldn’t.

“Can you come to the house?” he asked. “When he’s discharged?”

“I can,” Dr. Alvarez said. “We’ll talk about options. No decisions, just information. The kindness we owe them starts with telling the truth.”

When Michael returned to the room, Earl was watching the game show with a distracted frown, like the contestants’ frantic guessing offended his sense of pacing.

“That the dog doctor?” Earl asked.

“Yeah,” Michael said, sinking back into the squeaky chair. “She wants to come by the house. Talk about making Duke comfortable. Talk about… later, if we need to.”

“Later,” Earl repeated, the word sitting heavy between them. “Seems like everything’s about later now. Do this so you have more later. Don’t do that so you don’t lose your later. Nobody tells you what to do with the now.”

Michael studied his father’s profile, the deep lines carved by years of squinting into sun and storms. “Maybe that’s on us,” he said. “Maybe we have to figure out how to use what we’ve got left that doesn’t hurt him, or you.”

Earl turned his head on the pillow, meeting his son’s eyes in the dim light. “You planning on sticking around long enough to help with that?” he asked.

It wasn’t an accusation this time, just a question with the weight of a hundred missing weekends behind it.

“Yeah,” Michael said, surprising himself with how steady it came out. “I am.”

Duke was allowed up to the room later, just for a few minutes, a special favor from a nurse who had a picture of her own old dog taped to her badge. He padded in slowly, nails tapping the linoleum, tail swishing low. When he reached the bed, he rested his head on Earl’s hand, eyes closing as if relief flowed both ways.

“That’s my boy,” Earl whispered, fingers sinking into the familiar fur. “Look at us, huh? Two busted engines and not enough sense to stay out of trouble.”

Michael watched them, something in his chest untwisting and rewinding all at once. For the first time, the thought of time—more of it, less of it, how they’d spend whatever they had—felt less like an abstract threat and more like a task they might actually share.

Night deepened outside the narrow window, the parking lot lights painting vague circles on the asphalt. In a world scrolling past their story on glowing screens, arguing about what they should do next, the old man, the old dog, and the once-absent son fell into a fragile, exhausted peace. It would not last forever. Nothing did. But it was something real in a room full of beeping machines and numbers.

And in the quiet between heart monitor blips, the shape of the days ahead began, just barely, to come into focus.

Part 7 – Golden Days

They discharged Earl with a paper bag of new prescriptions and a stack of instructions that made him feel like he’d been handed the rulebook to a game he hadn’t agreed to play. Michael tucked the papers neatly into a folder, nodding along as the nurse explained schedules and warnings, his city-trained brain already breaking the information into manageable pieces.

“Remember,” she said, pausing at the door. “You don’t have to do this alone. Call if you’re worried. About your heart or about that dog.”

“Everybody’s awful interested in my heart all of a sudden,” Earl muttered as they wheeled him toward the exit. “Never got this much attention when it was busy breaking quietly.”

Outside, Duke waited by the truck with Noah and his mother. The boy’s hand rested on the dog’s back like it had grown there. When he saw Earl, Noah’s face lit with a kind of relief that had nothing to do with videos or views.

“You scared us,” Noah said. “You can’t do that. That’s Duke’s job.”

“I’m not trying to make a habit of it,” Earl replied. He squeezed the boy’s shoulder. “How’s school?”

“Better now that I’m not lost in the woods,” Noah said. He dug in his pocket and pulled out a folded piece of paper. “We made this for you. Me and my class.”

Earl unfolded it to reveal a drawing, the kind only ten-year-olds can make: bold lines, wild colors, perspective all wrong and feelings all right. It showed a big white dog and a thin man in an orange vest standing between a stick-figure boy and a wall of green scribbles labeled “FOREST.” Above them, someone had written, in shaky block letters, THANK YOU FOR FINDING ME.

He cleared his throat. “That’s some fine art there,” he said.

“You have to put it on your fridge,” Noah insisted. “It’s a law.”

“I’ve broken worse,” Earl said, but he folded the drawing carefully and slid it into his jacket pocket like something made of glass.

Back at the house, life reshaped itself around new routines. Michael set up pill organizers on the counter, labeling each section with a sticky note until even Earl had to admit it made things easier. He moved a chair into the bedroom so his father could sit while pulling on his socks instead of balancing on one leg like a stubborn crane.

For Duke, Dr. Alvarez arrived with a kit and a quiet firmness. She examined him on the living room rug, her hands gentle but thorough, her voice a steady stream of reassurance.

“His joints are very inflamed,” she explained. “We can increase his pain meds, add something for his nerves. It won’t make him young again, but it will make the edges of the day softer.”

“Edges have been pretty sharp lately,” Earl said, watching the way Duke relaxed under her touch.

“We’ll also talk about what his good days look like,” she continued. “So when the bad ones outnumber them, you’ll recognize it. That way, when the time comes, it won’t be a surprise attack. It’ll be… something you walk toward together.”

Michael swallowed. “You make it sound almost manageable.”

“It never is,” she said. “But planning is a kindness. For him and for you.”

The fundraiser money, handled by the town clerk and overseen by a small committee that refused to let Earl feel like he was pocketing strangers’ charity, went to the things he would never have bought himself.

They built a ramp over the front steps so Duke could walk out without being carried, his pride spared as much as his joints. A neighbor who knew roofs replaced the worst of the sagging shingles, paid in part by the fund and part by Earl’s famous chili, which turned into an improvised block party on a Sunday afternoon.

Someone dropped off a large orthopedic dog bed, the kind advertised as “memory foam oasis for seniors.” Duke eyed it suspiciously at first, sniffing every corner, then sank onto it with a groan that sounded disturbingly like Earl settling into his recliner.

“See?” Michael said. “Now you’re both spoiled.”

“Don’t get used to it,” Earl told the dog, who promptly started snoring.

With the worst of the physical worries temporarily cushioned, they made a list. It began as a joke—a “bucket list for an old hound”—but it became a quiet mission.

“Swimming hole,” Michael said, pen hovering over the paper.

“He just wades now,” Earl replied. “But yeah. He always did like that flat rock where the sun hits in the afternoon.”

“Long truck ride with all the windows down?”

“Until the dust makes us both sneeze.”

“Visit Mom’s grave,” Michael added, softer. “He used to sleep under that tree when you went.”

Earl nodded, the memories threading together with a tenderness that still hurt. “We’ll bring her some flowers that aren’t from the supermarket this time,” he said.

They checked off items one by one over the next few weeks.

At the swimming hole, Duke eased into the water slowly, legs stiff but determination intact. He stood belly-deep, eyes half-closed, the current massaging tired muscles. Earl and Michael sat on the bank, shoes off, feet in the cold water, saying very little and somehow saying a lot.

“Remember when he dragged your cousin Danny in there?” Earl asked.

“Danny slipped,” Michael said. “That’s my version and I’m sticking to it.”

At the cemetery, Duke lay down by the familiar headstone, muzzle resting on his paws. Earl and Michael stood nearby with a jar of wildflowers they’d picked from the edge of the property.

“Hey, Linda,” Earl said, voice low. “We brought the boys. The big one finally came home willingly. The furry one still thinks he runs the place.”

Michael smiled sadly. “She would have loved this,” he said.

“She would’ve told me I waited too long to ask for help,” Earl replied. “And she would’ve made you take some leftovers back no matter how far you drove.”

At sunset, they sat on the front porch almost every evening, Duke stretched between their feet like a furry bridge. The sky painted itself in oranges and pinks, the kind of show people in the city forgot was free. Michael worked remotely some days, laptop balanced on his knees, pausing often to look up and realize the world was still turning even when his inbox said otherwise.

Occasionally, someone would drive by slow, roll down a window, and shout, “How’s our hero doing?”

Duke would lift his head, give a polite wag, then go back to pretending he’d retired from public life.

Online, new videos appeared—not of rescues, but of small, ordinary moments. Noah’s mother posted a short clip of Duke dozing while Noah read a book aloud beside him, stumbling over big words, patting the dog when he got through a paragraph. Someone else snapped a picture of Earl and Duke at the farmer’s market, both of them squinting at a display of homemade dog treats like they suspected a scam.

The comments were still there—opinions about euthanasia, about aging, about what people owed their animals—but they felt farther away now, like weather in another state. Earl’s phone lived on the kitchen counter, more often used for checking in with the clinic than reading what strangers thought.

Despite the good days, the bad ones gathered in the corners like dust. There were mornings when Duke didn’t want to get up at all, when his eyes were bright but his legs refused the command. There were nights when no combination of medication and careful bedding could make him lie down without a soft cry, the sound scraping across Earl’s nerves like sandpaper.

On one of those nights, Earl found Michael sitting on the floor beside Duke’s bed at two in the morning, laptop abandoned on the couch. The glow from the lamp painted tired shadows under his eyes.

“You should be asleep,” Earl said.

“So should he,” Michael answered. He stroked Duke’s ear gently. “He keeps trying to stand up, then changing his mind. Like he’s afraid he’ll miss something if he lies down.”

“Old habits,” Earl said. “He was always the first one to hear trouble.”

“Maybe he’s listening for us,” Michael said. “To see if we’re ready.”

Earl leaned against the doorway, arms folded tight. “Ready for what?” he asked, even though he knew.

“To let him stop trying so hard,” Michael said. “To stop asking him to stay because we’re scared of what happens to us when he goes.”

The room went very quiet. Duke’s breathing rasped softly in the space between their sentences.

“I hate that you might be right,” Earl said.

“I hate that I am too,” Michael replied. “Dr. Alvarez said we’d know when his good days started to look like exceptions instead of the rule. I think… I think we’re there.”

Earl stared at his dog, at the gray fur around his eyes, at the way his chest rose in shallow, careful gulps. He thought about their list, mostly complete now. He thought about Tom on the forest floor and Linda in the hospital bed and all the times he’d waited too long because he’d been too stubborn to admit loss wasn’t something you could out-hunt.

“Call her in the morning,” he said finally, the words heavy but steady. “Tell her we’re ready to talk about… the last part.”

Michael nodded, tears gathering that he blinked back without much success. “Okay,” he said. “But tomorrow, when the sun’s up. Tonight he gets every ear scratch he can handle.”

Earl stepped into the room and lowered himself onto the floor more slowly than his pride liked. He rested one hand on Duke’s chest, feeling the labored thump, the effort it took to keep going.

“You did good, soldier,” he whispered. “You’ve more than earned your rest.”

Duke’s eyes flickered open, just enough to find Earl’s face, then closed again. His tail gave one last small, contented thump.

Outside, the wind shifted in the pines, carrying the faint smell of rain. Inside, between the two men who had finally learned how to share both worry and gratitude, a decision took shape—not because strangers online demanded it, but because love, when it’s done right, eventually asks you to let go.

Part 8 – Mercy Lines

Dr. Alvarez returned on a bright, deceptively cheerful morning, a canvas bag over her shoulder and a tired kindness in her eyes that said she’d walked other families through this valley before. Duke lay on his bed by the window, the sunlight warming his fur. His tail wagged when she came in, but he didn’t try to stand.

“How are my two favorite troublemakers?” she asked, kneeling to stroke his head.

“Depends who you mean by ‘two,’” Earl said from the table, a mug of coffee cooling between his hands.

“You and Duke,” she said. “Your son’s only trouble on alternate weekends.”

Michael offered a weak smile. “I can be flexible,” he said.

She did a quick examination, checking Duke’s gums, his pulse, the range of motion in his joints. He tolerated it with the resigned patience of someone who’d decided to trust her long ago. When she finished, she sat at the table with them, the dog between them like the center point of a compass.

“I’m not going to dance around it,” she said. “We’ve made him more comfortable these past weeks. The medication is doing what it can. But his disease is progressing. His mobility is very limited now, and the pain is harder to control without making him too sleepy to enjoy the day.”

“He sleeps a lot,” Earl said. “But when he’s awake, he still… looks like himself.”

“That’s the hardest part,” she replied. “They don’t complain the way we do. They don’t tell you all the math they’re doing just to get from here to the door.”

Michael nodded, throat tight. “He had a bad night again,” he said. “We made a list like you suggested. Good days, bad days. The bad ones are winning lately.”

Dr. Alvarez folded her hands. “So we talk about options,” she said. “We can continue exactly as we are, knowing the bad days may increase. We can adjust meds a bit more to buy a little time, understanding that he’ll be more sedated. Or…”

“Or we can help him out,” Earl finished.

She met his eyes. “Or we can schedule a time to say goodbye in a way that is calm, familiar, and as free from fear as we can make it,” she said. “Here, at home. With you beside him.”

The word “schedule” felt obscene and necessary all at once.

“How do people… decide?” Michael asked.

“There’s no formula,” she said. “Some people wait until the last possible moment, when the animal can no longer stand, eat, or respond. Some choose an earlier point, when there are still more good moments to hang onto than bad, so their last memory is not of unbearable struggle. Both choices come from love, even if they look different from the outside.”

“What would you do?” Earl asked.

She hesitated. Doctors weren’t supposed to answer that. But she’d been in his house, had seen the pictures on the wall, had watched him kneel in the yard to let Duke sniff the first snow.

“If he were mine,” she said quietly, “I would spend the next few days doing all the small things he enjoys that he can still do. Eating something delicious. Sitting in the sun. Being with his people. And then I would choose a day soon, not months from now, to let him go while he still recognizes the world he loves. While he still knows your voice.”

Earl looked at the dog. Duke’s eyes met his, cloudy but steady. Their conversations had never needed words.

“Friday,” Earl said, surprising them both. “Give us until Friday.”

“That’s four days,” Michael said, as if the number might be negotiable.

“Long enough to do the things,” Earl replied. “Not so long that we start lying to ourselves about why we’re waiting.”

Dr. Alvarez nodded. “I’ll clear my schedule,” she said. “We’ll come here. It will be quiet. He’ll be in his spot, with you. He’ll drift off like he’s falling asleep.”

“We aren’t talking about needles and… all that?” Michael asked, wincing.

“We are,” she said gently. “But you won’t see anything frightening. You’ll see him relax. If you want details, I can give them. If you don’t, you can let me handle the mechanics while you handle the love.”

They chose the second option.

After she left, the house felt both fuller and emptier. The date circled itself in their minds, big and red even without a calendar.

“Friday,” Michael said, staring at the refrigerator door as if expecting the day to appear there in magnets.

Earl took a long breath. “You remember when we used to plan hunting trips weeks in advance?” he asked. “Sharpening knives, checking boots, making lists.”

“Yeah,” Michael said. “I remember mom complaining about the smell of that duffel bag.”

“This feels like that,” Earl said. “Except this time, I’m not coming back with anything but memories.”

He walked to the fridge and pinned Noah’s drawing there with a magnet shaped like a trout. The stick-figure boy, the scribbled forest, the big white dog.

“He deserves more than me pretending I can’t read the signs,” Earl said.

The next days became a blur of small, sacred errands.

They grilled chicken and let Duke have more than his usual share, laughing when he licked the plate with a thoroughness that suggested he believed in no food waste.

They spread an old blanket in the yard under the big maple tree and lay beside him, talking about nothing and everything while he dozed with his head on Michael’s leg. Neighborhood kids drifted by, some bold enough to ask if they could pet him, some just waving from the sidewalk, their parents hovering behind.

Noah came after school with a shoebox full of “presents”: sticks he claimed were special, a worn-out tennis ball, a crumpled ribbon he insisted was a medal.

“He saved me,” Noah told Michael in a serious whisper while Duke napped. “Do you think he’s scared?”

“I think he feels safe that you’re here,” Michael said. “I think dogs understand things we can’t. Maybe he knows it’s our turn to be brave.”

On Thursday night, Michael sat on the porch steps, phone in hand, thumb hovering over the social media app he’d avoided opening for days. Curiosity and dread finally won. He tapped.

The fundraiser had doubled again. The town had voted to use the extra funds, after vet bills and home repairs, to start a small program in Duke’s name: help for seniors who needed veterinary care for their pets. The inaugural picture showed an elderly woman in an apartment holding a cat, a box of supplies at her feet. The caption read, “Duke’s Gift: Helping our elders keep their four-legged family.”

Underneath, a debate raged, as always.

Are they really putting him down on Friday? Does anyone know?

It’s not your business. Let the man make his choice.

How can you call it mercy when he just saved a kid?

Because mercy isn’t about what makes us feel good. It’s about what eases their pain.

Michael set the phone down, heart pounding. The idea that strangers were circling a date on their mental calendars, waiting to judge, made his skin crawl.

Inside, Earl stood by the kitchen counter, staring at his own phone like it was a snake. “They keep calling,” he said. “Reporters. People from outside the state. One woman said her followers demand I reconsider.”

“Block them,” Michael said. “Turn it off. This isn’t a public vote.”

Earl did just that, powering the device down with a final, decisive tap. The silence that followed felt like a curtain dropping between their small, aching story and the noisy world.

“Tomorrow,” Earl said.

“Tomorrow,” Michael echoed.

They slept little that night. Michael lay awake listening to the house breathe—old wood settling, a branch tapping against the window, Duke’s uneven rhythm rising from the living room. Once, he heard his father’s footsteps pad down the hall, heard the low murmur of his voice talking to the dog. He didn’t try to make out the words. Some goodbyes belonged to them alone.

By morning, they had all talked more about love, regret, and gratitude in four days than they had in years. And still it did not feel like enough.

Friday dawned clear and cool, a thin mist clinging to the low parts of the yard. Birds were louder than usual, or maybe they simply noticed them more.

Earl stood at the window, mug untouched in his hand. “One more walk,” he said. “Before she comes.”

Michael blinked. “To the yard?”

“To the pines,” Earl replied. “Where he pointed that boy out. Where he’s always been most himself.”

“You’re sure that’s a good idea?” Michael asked. “The truck, the drive, the uneven ground…”

“If he can’t make it, we turn back,” Earl said. “But if he can, I’m not letting him leave this world without saying goodbye to the only place that ever made sense to us.”

Michael swallowed. “You want me to drive?”

“I want you beside me when we decide when to turn around,” Earl said. “That’s all.”

They looked at Duke. He struggled to stand, legs shaking, but when he saw Earl pick up the leash and the old rifle case out of habit, he perked up in a way that broke Michael’s heart and stitched it in the same breath.

“Okay,” Michael said. “One last hunt. Without the hunting.”