Part 1 – The Dawn Appointment

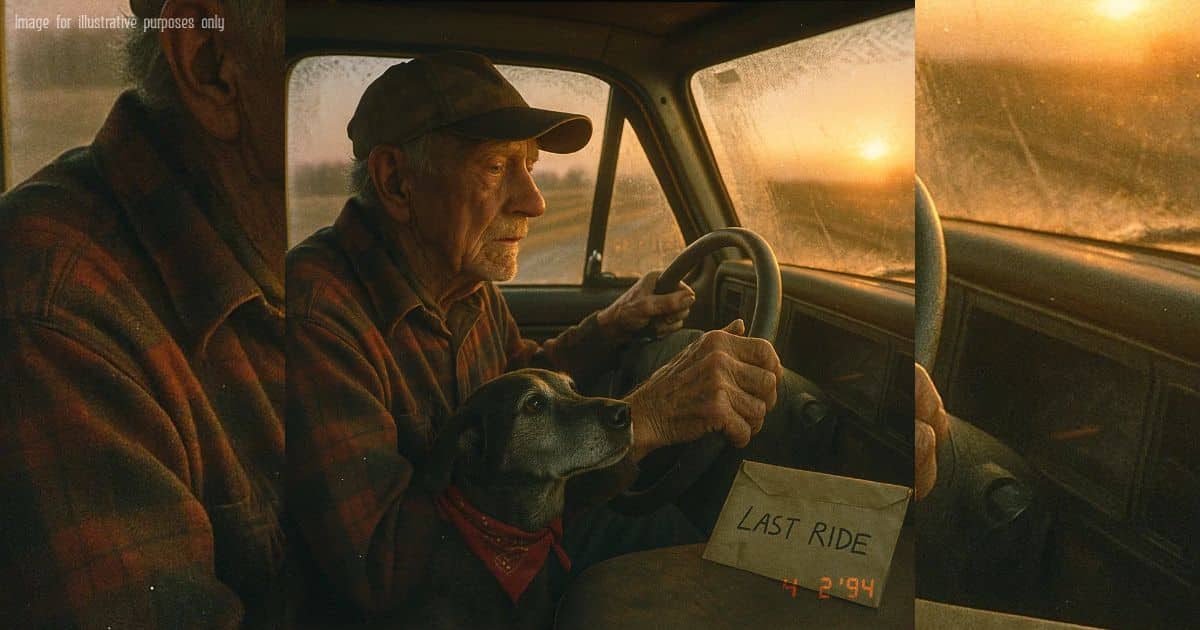

At sunrise, Walt Halpern tied a red bandana on his old farm dog, set an envelope labeled “Last Ride” atop eighty-seven crumpled dollars on the dashboard, and drove to ask a stranger for mercy. He loved Scout enough to do the one thing that was breaking him.

The gravel popped under his tires like small bones. Frost clung to fence wire and the fields wore that dull pewter light that makes a man count what’s left. Walt’s hands shook on the wheel, but he kept them there, like a promise he didn’t know how to keep.

Scout leaned into him at every turn. The dog smelled like hay and October and the back porch where Walt’s late wife used to knit until the sky went purple. Fourteen years, and the dog still watched him the way only something born loyal can watch a breaking heart.

He told himself this was kindness. He told himself the hurt belonged to him, not to Scout. He told himself he’d tried everything a poor old farmer could try, and sometimes love means knowing when to stop.

They rolled into the first gas station on the highway. The bell above the door clanged tiredly and the clerk nodded without looking up. Walt reached for the coffee urn, but Scout stiffened, then gave a raw, throaty bark that didn’t sound like pain at all.

The dog pulled toward the back hallway, nails skittering on tile. A bitter scent hit Walt a beat later, the kind that crawls behind your eyes. He set the cup down, heart suddenly loud. “Something’s off,” he said, and the clerk’s head snapped up.

“Smell that?” Walt asked. The clerk went pale and reached for a phone. Walt pushed the front door open, propped it with a rubber mat, and motioned a couple of early customers outside. He didn’t shout, didn’t panic. He just moved like a man who’s seen winters and knows how to keep people calm.

They stood in the parking lot with their breaths smoking the air. Scout pressed against Walt’s knee and watched the building as if it might bite. A siren sounded faint and then nearer. The clerk lifted a shaky hand in thanks. Walt tipped his cap and said nothing heroic.

Back in the truck, he scratched the soft spot behind Scout’s ear. “Still earning your keep,” he whispered. Scout sighed and let his weight settle, as if the earth had tilted to put them back where they belonged.

The veterinary clinic sat between a hardware store and a church with a peeling white steeple. The sign out front just said “Animal Care,” nothing shiny, nothing cruel. Walt killed the engine and stared at his own face in the windshield, thinner than it used to be.

Inside smelled like sanitizer and peanut butter treats. A young tech with a messy bun and a name tag that read JUNE met them with a gentle smile. “Hi there, sir. That’s a handsome bandana.”

“He’s got a couple left,” Walt said. “More than I do.”

June crouched and let Scout sniff her fingers. “We can talk through options,” she said softly. “Comfort care is a real thing. We can’t stop the years, but we can help the days feel better.”

Walt set the envelope on the counter. “I don’t have much,” he said. “Enough for… you know. Or almost enough.”

June didn’t glance at the money. “Let’s start with a scan and a quick check. No commitments right now. Just information. How’s that?”

They stepped into an exam room where the walls held drawings from local kids. June passed a wand over Scout’s shoulder blades and a small reader chirped. She smiled. “Chip found. Good.”

She ran it again to confirm. The device chirped a second time, sharper, as if surprised by itself. June frowned, then tried a different angle. It chirped again, the sound like a digital echo inside a quiet church.

“That’s odd,” she murmured. “Looks like there are two records tied to him.”

Walt blinked. “Two?”

June tapped the screen and pulled up a file. “Scout Halpern,” she read first, and smiled at Walt. Then her eyes shifted as a second listing populated beneath the first, older and dustier somehow, the way a name can feel like a photograph. “And… Scout Carter.”

She looked up. “Did you ever register him before you had him?”

Walt shook his head. “We found him years back after a flood took the fence line. He wandered in like he was sent.”

June scrolled, lips pressing into a thin line of focus. “There’s a contact,” she said. “Evelyn Carter. Same town, different side of the highway back then.” She hesitated. “There’s also a note on the old file.”

Walt swallowed. Scout rested his chin on the exam table and watched June with calm, old eyes. Outside, the church bell counted ten and then stopped like it had remembered something important.

June read the note twice before she spoke. “It says: ‘If located at end of life, please inform caregiver of small designated fund to cover comfort care and to say thank you. Never claimed.’”

Walt felt his fingers go numb around the brim of his hat. “A fund,” he said, not trusting the word to be real.

“It’s not charity,” June said, as if she’d heard the argument forming. “It’s attached to the dog. It belongs to his care, not to anyone’s opinion.”

He stared at Scout’s graying muzzle. He thought of the gas station, the way the dog had barked before he himself had known danger was in the air. He thought of his wife humming over knitting needles, promising the dog he was home for good.

June’s phone vibrated softly on the counter. She glanced at it and then back to Walt. “Evelyn Carter is still at the number on file,” she said quietly. “Would you like me to call her? Or…” She nodded toward the envelope. “We can keep the appointment you came for.”

Walt’s thumb worried a groove into the cardboard edge. The room felt smaller, and the years felt longer, and Scout’s tail tapped the table like a slow metronome, measuring out the heartbeats he had left.

June’s eyes were kind but steady. “Mr. Halpern,” she said, holding the reader where he could see both names side by side, one new and one that had waited for years. “Do you want to hear how your dog already had a goodbye planned for him—before he ever found you?”

Part 2 – Old Chip, New Name

June held the reader so I could see both names. The screen glowed like two porch lights in early dusk, one labeled Halpern, one labeled Carter, and both somehow pointing at the same old dog breathing slow beside us.

“I can call her,” June said. “Or we can wait. You tell me.”

I felt the envelope in my pocket like a hot coal. The words “Last Ride” pressed through the paper as if ink had weight. I had walked in here a man with one decision and now I was standing in a room with two doors, both of them labeled love.

“Before we call,” I said, “let me tell you how he got here.”

June eased onto the stool and scratched the loosened fur at Scout’s neck. The clinic hummed with soft machinery and the rustle of treat bags. Somewhere out front a cat carrier rattled and a child laughed like wind chimes.

“The flood was nine summers back,” I said. “Fence line went under, tools floated like boats, and the pasture turned mean. I found him the next morning in my bean rows, ribs like broom handles, bandana black with mud.”

June listened with both eyes, a practice you learn only if you care. Scout lifted his head and laid it over my wrist. His tail brushed the steel table the way old clock hands brush noon.

“My wife was still alive then,” I said. “She looked at him and said, ‘Well, we were due for a miracle,’ like she was naming the weather. She scrubbed that bandana clean and tied it on fresh. He fell asleep with his chin on her shoe like he’d paid rent.”

June smiled and waited. The room smelled faintly of oatmeal shampoo and the sharp promise of sanitizer.

“We posted flyers,” I said. “We asked at church and the feed store. No one claimed him. I told myself if somebody came along and said, ‘That’s my dog,’ I’d do the right thing, but nobody did. He stayed, and we stopped asking.”

June reached over and set a small stack of paper towels near me, a kindness I pretended not to need. Scout’s eyes had that tea-stained brightness old dogs get when the day is good and the person they love is near.

“I don’t take handouts,” I said after a minute. “I don’t say that to be proud. I say it because I wouldn’t know what to do with myself if I did. I work a thing, or I go without it.”

June nodded like she’d already guessed and liked me anyway. “This is different,” she said. “This is a note attached to love. If someone left money so Scout could have comfort when the time came, then using it is honoring their plan, not breaking yours.”

The word comfort landed like a quilt. It didn’t change the winter, but it made something bearable.

“What if she’s gone?” I asked. “What if the number is wrong or the person on the other end doesn’t want to hear from the past?”

“Then we make a plan with what we have,” June said. “A gentle one. Pain control, warm places, easy food, and short walks where the memories are best.”

I swallowed and nodded. The envelope in my pocket felt smaller.

June tapped the screen again and the second file expanded. “It says ‘Scout Carter.’ Owner of record: Matthew Carter. Secondary contact: his mother, Evelyn. Address from years ago, phone number current as of the last update.” She paused. “There’s a line about Matthew that looks like an obituary note. No details. Just dates.”

My mouth went dry. I thought of all the ways a life can end and all the ways a dog can hold the last soft piece of it. I thought of the care someone took to write that small sentence about a small fund, and to trust the world to keep it safe until it was needed.

“Call her,” I said, before I could climb back into my stubbornness.

June put the phone on speaker and dialed. The ring was a long road. The second was longer. On the third, a voice answered with the careful calm of someone who has learned to expect both bad news and ordinary salesmen.

“Hello, this is Evelyn.”

“Hi, Ms. Carter,” June said, bright but gentle. “My name is June. I’m a tech at Animal Care in—”

“I know it,” Evelyn said. “It used to be next to the hardware store where my boy bought nails he didn’t need. Is this about a chip?”

June glanced at me. “Yes, ma’am. We have a dog here named Scout. Our scanner shows two registrations. One current with a Mr. Walt Halpern, who is with me, and one older listing under your family name.”

Silence came like snow. Not hostile, not shocked. Just soundless.

“Scout,” Evelyn said, and the word bent into a smile you could hear. “He loved that dog more than he loved his truck. And he loved that truck only because it could take the dog places.”

June waited. Good waiting is its own kind of medicine.

“My son passed,” Evelyn said, her voice steady the way a flag is steady even when it’s frayed. “He came home from things I still don’t ask about and tried to learn how to sleep again. That dog put his head on my boy’s chest at night and kept watch. The only time my boy laughed without thinking first was when Scout stole a biscuit and ran crooked around the coffee table.”

I pressed my knuckles against the steel to keep from interrupting the life I was hearing.

“When the river rose,” Evelyn said, “Scout slipped loose in the mess. We searched three days and two nights that had more years in them than most months. My boy kept saying, ‘He’s just a dog, Mama,’ but he said it like ‘He’s the part of me I can’t lose.’ Then the fever took my boy a winter later. I put a note on the chip because grief makes you plan in strange directions. I figured if that dog ever turned up when he was old and tired, whoever had him would be the person who loved him right. I wanted to say thank you to them, in the only language that still worked.”

June met my eyes. I looked down first.

“My name is Walt,” I said, leaning toward the phone. “Ms. Carter, he’s been with me nine years. He’s family. I was about to do something hard today because I thought it was the kindest thing left. Then we found your note.”

Evelyn breathed out, a sound like someone setting down a box they’ve carried too long. “I’m sorry for your hard day, Mr. Walt. I’m grateful you made it this far with him. That means you taught him what home feels like twice.”

I blinked fast and let it pass without comment. June clicked her pen and wrote nothing, a small courtesy that said she would keep quiet as long as needed.

“I don’t want to take anything from you,” I said. “I don’t want to unmake your son’s house in either of your hearts. I only want to do right by this old dog who smells like hay and becomes the best thing in any room he’s in.”

“You already did,” Evelyn said. “Maybe now it’s my turn to help you do it the rest of the way.”

We talked like neighbors who had never met but had shoveled the same driveways after different storms. Evelyn asked about his appetite and his favorite place to nap. I told her about the back porch and the sun line that moves across it like a slow blessing. She asked if he still chases shadows. I told her not so much anymore, but he watches them like he’s making a list.

June explained the comfort-care plan without numbers sharp enough to bruise. Short walks. Gentle meds. Soft bedding that keeps hips from complaining. A warm sweater on mornings when the air bites. She said none of this would stop the clock, but it would make the ticking kind.

Evelyn said she had the paperwork for the fund. It was small, but it was meant to be a key, not a house. It could open the door to the weeks a dog deserves when the calendar grows thin.

“I’ll bring the documents by,” she said. “If you don’t mind a visit from a woman who talks to dogs like they can answer full sentences.”

“I live with one,” I said. “I mind nothing.”

Scout shifted and put his paw over my boot. He does that when a decision arrives in a room before I do. June slipped him a chew that smelled like apple. His tail thumped once, a polite thank-you.

“Before we hang up,” Evelyn said, “may I ask Mr. Walt one question?”

“Yes, ma’am,” I said.

“Did he keep the bandana?” she asked. “It was red once. My son tied it on when they left the shelter so nobody would mistake Scout for lost. He said a gentleman wears a splash of color.”

“He kept it,” I said. “It’s on him now. It’s the last clean one we have.”

Evelyn laughed softly, and then the laugh turned into something the body does when it remembers everything at once. She caught herself quick. “If Scout is with you, Mr. Walt,” she said, “then maybe the story isn’t finished the way I thought. Maybe the Lord hasn’t given permission to close it yet.”

We hung up after addresses and directions and the promise of afternoon. June set the phone down like it was a fragile heirloom. I sat there a long moment with my hands on the table and my eyes on the dog who had somehow managed to be two people’s miracle in one lifetime.

Out in the lobby, a bell chimed and a new voice asked about flea shampoo. Life kept going the way life insists on going. June slid a pamphlet toward me, not sales, just information, and pointed to the part about warm places and slow food.

“I think we can buy Scout some good days,” she said. “Would you like to try?”

I folded the envelope in half and then in half again until it was the size of a postage stamp. It wasn’t gone. It was just smaller than what had replaced it.

“Let’s try,” I said. “And when Ms. Carter gets here, we’ll listen to the rest of the story we didn’t know we were in.”

Part 3 – The Price of Pride

June printed out the comfort-care plan and tucked it into a manila folder like it was a map meant for slow roads. She underlined the parts about warmth and soft food and short walks where the memories live. I signed the places she pointed and tried to ignore the part where my hand shook.

She handed me a small bag. Inside were pills wrapped in clear sleeves, a joint supplement that looked like a treat, and a knit cover for a rice sock you heat in the microwave. “Ten minutes on his hips before bedtime,” she said. “It’s simple and it helps.”

I nodded like a man who knows how to follow directions if someone writes them big enough.

Scout thumped his tail once and leaned into June for a goodbye. She tucked a sticker on his bandana like a medal and grinned at me over his head. “We buy him days,” she said, quiet but sure. “You don’t have to carry every one of them alone.”

I drove home by the long road because the long road hurts gentler. The fields were stubbled and the ditches held a thin curl of ice. Scout watched fence posts go by with the interest of someone counting on both hands and then starting over.

At the farmhouse, the porch steps still had that hitch where one board sags and another pretends not to. I lifted Scout down with an old blanket under his belly the way June showed me. He grumbled and then kissed the air near my chin as if to say, Fine, we’ll do it your way.

Inside, the place smelled like coffee that’s been thinking too long and cedar from the old hope chest by the window. I folded a quilt on the floor and slid the rice sock under his hips until he sighed and shut both eyes like a curtain.

Evening thickened fast. That’s when pain walks the halls and checks the locks. Scout settled but not all the way. He let out a small sound now and then, not a complaint, just a report.

I brewed tea and sat on the floor so his head could find my knee without trying. The dog and the man made their peace with the clock for another night.

Morning was crows and frost halos on the pasture. Scout stretched like a creaking gate and then wagged twice because the sun had shown up just like it promised. I warmed the rice sock, whispered thanks to the knit sleeve, and watched him relax into something easy.

After chores, I drove to the clinic with people in it instead of animals. The doctor took my blood pressure, listened to my chest, and used words that were gentle without being kind enough to lie. He told me to eat, to rest, to ask for help, and to stop pretending I was built from wire.

“I’ve been worse,” I said.

“You don’t get extra credit for that,” he said back, and smiled like he knew I’d try anyway.

At the feed store I bought less than I needed and carried it like more. Mrs. Alvarez told me her tomatoes gave up late this year and pressed a jar of sauce into my hands without waiting for me to say no. “For the dog,” she said, and then laughed at herself. “For you both.”

On my way out, a young man I know from church held the door and said he saw a clip online of a dog at a gas station catching trouble before it started. He said his dad called it good old-fashioned sense. He didn’t say my name. He didn’t have to.

Lila was waiting on my porch steps like a shot of August in a January coat. She stood and dusted her jeans like the air had left chalk on them. “Mr. Walt,” she said, using the respectful tone she saves for people who could be grandfathers or old barns. “Two things. Good, I think. Maybe.”

She came inside and crouched to greet Scout like he was a mayor. He lifted one paw, polite as a handshake, and she grinned like someone had given her a birthday on a Tuesday. “Ok, three things,” she said. “Scout is still perfect. That’s the first one.”

I poured coffee, then remembered June’s voice about my blood pressure and poured half of it back. Lila pulled out her phone and tapped the screen. A grainy clip opened, not fancy, just honest. The gas station. Me in my old coat, opening the door and waving people out without drama. The clerk’s white face. Scout pulling hard, head low and serious, then leaning against me in the parking lot like an anchor.

“Mr. Walt,” Lila said, “this is making rounds on the town page and then some. People are saying a dog saved a morning and a man saved a breath for a lot of folks. They’re calling it what it is.”

I watched myself in small scale. I watched Scout be who he’s always been. A few comments scrolled by, hearts and hands and the word hero used like a blanket that everybody wanted to hold an edge of.

Then another set rolled up, the kind that tries to balance a story by tilting it. “If he can’t afford the dog, he shouldn’t have one,” one read, not cruel, just tidy. “Where’s his family?” someone asked, like family is an address you can check. “Why doesn’t the town step up?” another wrote, like kindness is a switch on a wall that a person forgot to flip.

I took a breath and set the coffee down before the cup remembered it was fragile.

“I can turn comments off when people get loud,” Lila said. “I can also invite the ones who want to help to do it in ways that don’t feel like orders.”

“I don’t want pity,” I said.

“I don’t offer it,” she said. “I organize chores.”

She showed me a draft post she’d written but not sent. It wasn’t a fundraiser. It wasn’t a story that spent people’s tears like small change. It was a list of things a neighbor could do without making a speech. A ride to the clinic if needed. A sack of kindling left on a porch. A batch of bone broth in a jar with no note. Twenty minutes of fence mending because you had the hammer in your hand anyway.

She put the phone down and looked at me full on. “We can keep your name off it,” she said. “We can keep Scout’s name off it. We can just make it about a gentleman and his old dog who both deserve soft landings.”

I tried on the picture in my head of kindness that didn’t put me on a stage. It fit better than I expected.

We ate sandwiches with too much mustard and Scout sighed loudly to remind us he hadn’t forgotten lunch. Lila fed him the joint treat like a communion wafer and told him he was excellent, which he knew.

June called mid-afternoon with a voice that carried daylight. “Mr. Halpern, I’m dropping off a couple extra rice socks and a bag of pumpkin. Also, a sweater someone donated that might fit Scout’s gentlemanly shoulders.”

“Tell the donor he’ll wear it like a magazine cover,” I said.

June laughed. “I will.”

Evelyn arrived near four with a tin of oatmeal cookies and a folder that held the world folded small. She stood on my porch and touched the doorframe like you do when you’re trying to be polite to a house. Scout took two steps and then three and then rested his chin on her knee as if he’d never forgotten a single word she’d said to him years ago.

“Hello, sir,” she whispered, and didn’t rush to pet him. She waited, and then she did, with one slow pass the way you smooth a wrinkle out of a good shirt.

She handed me the folder. The papers inside were simple, the way the truth often is when it’s hard. A bank note for the small fund, designated for end-of-life comfort care for a dog named Scout. A statement that the money was a thank-you to whoever had loved him when the river didn’t. Signatures. Dates. Brave little lines.

“I don’t want to crowd you,” Evelyn said. “I can sit on the porch and listen to the same wind my boy grew up under. I can go if the day is heavy. I just wanted to put this in your hands.”

“You’re welcome here,” I said. “You’re part of the story even when you aren’t in the room.”

We shared coffee and cookies and soft history. She told me how Matthew had taught Scout to bow for a biscuit by saying, “Be polite, sir,” and how the dog had never forgotten that good manners are a kind of love. I told her about the way Scout patrols the back porch at dusk like a sheriff, checking shadows and signing the air with his nose.

Dusk came on with that pink edge that makes you wish you could keep the color in your pocket. Scout slept with his head half on my boot and half on Evelyn’s shoe, because loyalty can sit with more than one person if the room is kind.

When the first star showed up, the porch light clicked on and made a small circle of gold that didn’t feel like it cut anything in half. Lila’s phone buzzed and she looked down, then up, then down again like the screen was telling her to be careful and brave at the same time.

“Mr. Walt,” she said, and her voice had that mix of apology and hope you only get when both things are true. “The town page posted the gas station clip again, but this time someone added, ‘That old farmer was on his way to put the dog down today.’ It’s not mean, just—blunt.”

I stared at the wood grain like it could answer for me. Evelyn reached out and set her hand over mine with the ease of a mother who has practiced keeping a storm from tipping a cup.

Lila swallowed. “I can ask the moderators to edit. I can ask them to remove your name. I can post our list instead and change the subject toward actual help.”

Scout opened one eye and then the other and gave me the look he uses when the barn door has blown wide and somebody needs to decide whether to chase it or tie it. I have never taken orders from a dog, but I have listened to good advice from one.

“Let’s tell it right,” I said finally. “No names. No blame. Just the truth that love is expensive in ways that money can’t count and sometimes in ways it can. And it’s worth paying.”

Lila nodded and started typing as if the keys were steps on a path we could share. June texted to say she was five minutes away with the sweater and that it made old dogs look like professors. The church bell across the road rang the hour and then one extra ring because it does that sometimes when the rope is in kind hands.

We sat there in the gold light while the town decided how to be itself. The comments kept coming like weather. Some were warm, some were dry, some were the useful kind that blow the smoke away so you can see your own front door.

The last thing before full dark was a message from Reverend Mike. It was short. It was the size of a seed. “Neighbors,” it read, “tomorrow night at the fellowship hall. No speeches. Just a circle and a sign-up sheet. We’ll listen more than we talk.”

Lila turned the screen toward me. Her eyes were wet but steady. “They’re not shouting,” she whispered. “They’re showing up.”

Scout lifted his head and put it on my knee with purpose, like the period at the end of a sentence that finally knew what it wanted to say.

And then my phone buzzed again, a new number I didn’t recognize, with a message that made the room tilt just a little: “Mr. Halpern, I’m the clerk from the gas station. We checked the back line. Your dog was right. We owe you both. Please open your door in five minutes.”

Part 4 – The Town Speaks Softly

The knock came at the exact minute the text promised. Evening had laid a red thumbprint across the sky and the porch light threw a soft coin of gold onto the steps. Scout stood, shook his old bones into order, and reached the door before I did like a man meeting company with his tie straight.

Two clerks from the gas station stood on the mat with caps in hand. The younger one was the boy who’d gone pale that morning; the older one wore a jacket with grease on the cuff that said he worked for a living. Between them was a cardboard box and a paper envelope with my last name printed in careful block letters.

“We checked the line out back,” the older clerk said. “Your dog smelled what our sensors didn’t. We owe you a better day for catching a worse one.”

I opened the box and found what useful people bring when talk won’t do. A carbon monoxide detector still in its plastic, a bundle of handwarmers, two bags of senior kibble, and a gift card for fuel in an amount that would get a man to the clinic and back a lot of times. The envelope held a note with four sentences that didn’t try to be poetry.

“No names,” the younger clerk said. “No photos. Just thanks.”

I nodded and felt something in my chest give up its shape. Scout sniffed the handwarmers, decided they were not edible, and then leaned his whole left side into the older clerk as if to agree to a peace treaty. The men laughed the way people laugh when a hard moment opens a small window.

Lila kept her phone in her pocket and her eyes on the men. “Thank you for coming in person,” she said. “We’ve got the online part covered. The real world is better at carrying boxes.”

They left with handshakes and a promise to swing by Wednesday to check the porch railing where it wobbled on the far post. No speeches. No moral lessons. Just Wednesdays.

June arrived ten minutes later with the promised sweater, a loaf of pumpkin bread wrapped in a dish towel, and two extra rice socks stitched with little blue dots. She held the sweater up and grinned. “Professor Scout,” she said. “Are you ready to accept a visiting appointment at the University of Back Porch Studies?”

We slid his paws through the armholes and buttoned the chest. Somehow he looked older and younger at the same time, like the way a photograph can carry two birthdays. He lifted his chin, considered the effect, and then wagged twice to say he could live with it.

June set the rice socks by the stove and handed me a small pill organizer with morning and evening marked in letters big enough to read when the eyes are tired. “Pain control is a staircase,” she said. “We’ll take it one step at a time. If he stumbles, we go back down and try a different stair.”

She pulled a folded paper from her bag, a schedule printed in clean lines. “Tomorrow we’ll do gentle imaging,” she said. “He won’t need to be put under. It helps us see if this is mostly arthritis talking or if something else is trying to get a word in. The earlier we know, the kinder we can be.”

Evelyn set the pumpkin bread on the counter like an offering and touched the rice sock with her fingers as if memorizing the heat. “He always liked warmth,” she said. “My boy used to sit on the floor with him by the dryer and pretend they were camping.”

We made tea and sat like a small council with unequal ages and equal intentions. Lila showed June the town page draft—no names, no pity, just a list of tasks that looked like how people live when they remember how. Reverend Mike’s message chimed again, repeating the plan for the fellowship hall: a circle, a sign-up, a rule about listening more than speaking.

“Will you come?” Lila asked me.

“I might,” I said. “If I don’t, will they come anyway?”

“They will,” June said. “That’s the point.”

We ate slices of pumpkin bread that made the kitchen smell like a holiday without a date. Scout dozed with his chin on my boot and his sweater turned him into the sort of gentleman who could be trusted with keys. Evelyn watched him sleep with the kind of smile that doubles as a gate and a welcome sign.

When the light turned blue at the edges, June pulled a second folder from her bag. “There’s something I didn’t want to jam into the middle of a hard afternoon,” she said. “It’s about the old microchip record. I asked the registry to send a full transcript. There’s an addendum.”

I looked at the paper and then at Scout and then back at June. “Addendum,” I repeated, because some words need to be invited into a room twice.

She slid the page to me. The text was short and plain. It said that when the time came for end-of-life care, the caregiver of record should be “the person who understands Scout best.” It said release of the small fund could be finished with a simple attestation signed by the caregiver and countersigned by the secondary contact, confirming that understanding was present and documented.

“It isn’t a test in a cold sense,” June said. “It’s a promise in writing. But the registry does ask the clinic to attach a ‘care narrative’ as part of the file. Sometimes that’s a paragraph. Sometimes it’s a page.”

Evelyn leaned in, glasses low on her nose. “My son made me add that line,” she said. “He said a dog’s end should be handled by the person who can translate the little things. The three kinds of sigh. The way a paw means water or yard or worry. He wanted to make sure the paperwork nodded to that.”

I ran a hand over Scout’s neck and felt the warm place at the base of his ear go loose with trust. I thought about the map of his habits that lived in my hands. I thought about how he drinks more when the bowl is turned a quarter turn to the left and how he prefers the porch step with the knot in it because it presses his rib just so. I thought about his “enough” sigh and his “I’m listening” sigh and his “don’t move yet” sigh.

“What would a care narrative look like?” Lila asked.

“Stories,” June said. “Not data. ‘He will eat on a bad day if the food is warmed and the bowl sits on the third board from the stove.’ ‘He calms if the radio is on low with a voice, not music.’ ‘He sleeps best with a small nightlight and the front door locked.’ That sort of thing.”

Evelyn wiped her eyes once and smiled. “He does like a voice,” she said. “He used to fall asleep to the weather report like it was a lullaby.”

June pulled a pen from behind her ear. “Mr. Halpern,” she said, the way a friendly judge might say a name before something official but kind. “Would you be willing to tell us Scout’s language so we can put it in his file? It honors the addendum and it helps anyone who might need to step in if a day comes when you can’t.”

I opened my mouth, then closed it, not because I didn’t know the words but because I knew too many. The kitchen clock made a small sound like a cricket pretending to be a metronome. The sweater made Scout look like faculty and the rice sock steamed quietly in its knit sleeve.

“Let’s start small,” June said. “How does he tell you he’s thirsty?”

“He sits near the bowl and doesn’t look at it,” I said. “He looks at me instead. If I’m slow, he lifts his left paw onto my boot and leaves it there, not pushing, just reminding. He won’t drink if the water’s colder than the porch air.”

June’s pen moved fast. “How does he say he’s had enough of a walk?”

“He stops where the stone fence breaks and turns back without asking,” I said. “If I miss it, he’ll stand in place and yawn, not sleepy, just conversational. He hates to be carried home if his pride thinks he can finish.”

“And comfort?” June asked softly. “What tells you he’s content even when he hurts?”

“He hums,” I said, surprising myself with the word. “A little closed-mouth sound he makes when he settles in the sun stripe on the floor. It’s not a whine. It’s a hymn.”

Evelyn nodded like someone hearing a language she once knew and had been hoping to remember. Lila bit her lip and wrote the word hymn in the margin like a blessing.

We kept going, not too long, not too clinical. The radio station he tolerates. The corner of the quilt he chooses. The way he refuses the back seat unless my cap is there first, holding his place like a reservation at a diner that knows your order. June wrote and wrote and every line felt like folding a blanket and putting it where it belongs.

When we’d made a page and then a little more, June capped the pen. “That’s the best kind of medicine,” she said. “The kind where the room knows the patient.”

The church bell out the window rang seven and then stayed quiet, respectful of the hour. Lila’s phone buzzed with messages from the fellowship hall—photos of a circle of metal chairs, a big coffee urn, and a plain sign that read, “Neighbors.” No decorations. No slogans. Just neighbors.

“I can go,” Evelyn said, looking at Scout and then at me. “Or I can sit here and read this radio schedule out loud to an old friend who likes a voice.”

“You read,” I said. “I’ll walk over and shake a few hands and make sure the sign-up sheet understands plain English.”

Lila stood and pulled on her coat. “I’ll walk with you and come back with a list that doesn’t feel like a bill.”

June gathered the papers and tucked the care narrative into the folder with the chip addendum and the comfort plan. She pressed the folder flat with her palm like a prayer before a meal. “One more thing,” she said, and her voice went careful in a way that made me sit down before she finished.

“The registry asks for the caregiver to sign an attestation that says, in short, ‘I am the person who understands this dog best.’ It’s not legal thunder, but it’s a promise you make out loud with ink.” She looked at me, then at Evelyn. “The secondary contact countersigns to say they agree.”

Evelyn reached for the pen without hesitation. “I agree,” she said. “I knew it before I walked in, and the hymn confirmed it.”

June set the form in front of me. The line waited like a thin road asking a simple question that was not simple at all. Scout lifted his head, looked straight at me, and breathed that small, content sound that fills a kitchen without moving a single thing.

I picked up the pen and held it above the paper. The porch light flickered once as if a moth had given advice and flown on. From the fellowship hall, the sound of chairs scraping into a circle traveled across the two streets and one field that separate alone from together.

“Mr. Halpern,” June said, her words soft but steady as a hand on your back. “Are you ready to sign as his final interpreter—the one who hears what he says when he says nothing?”