Part 1 – The Window at 104°F

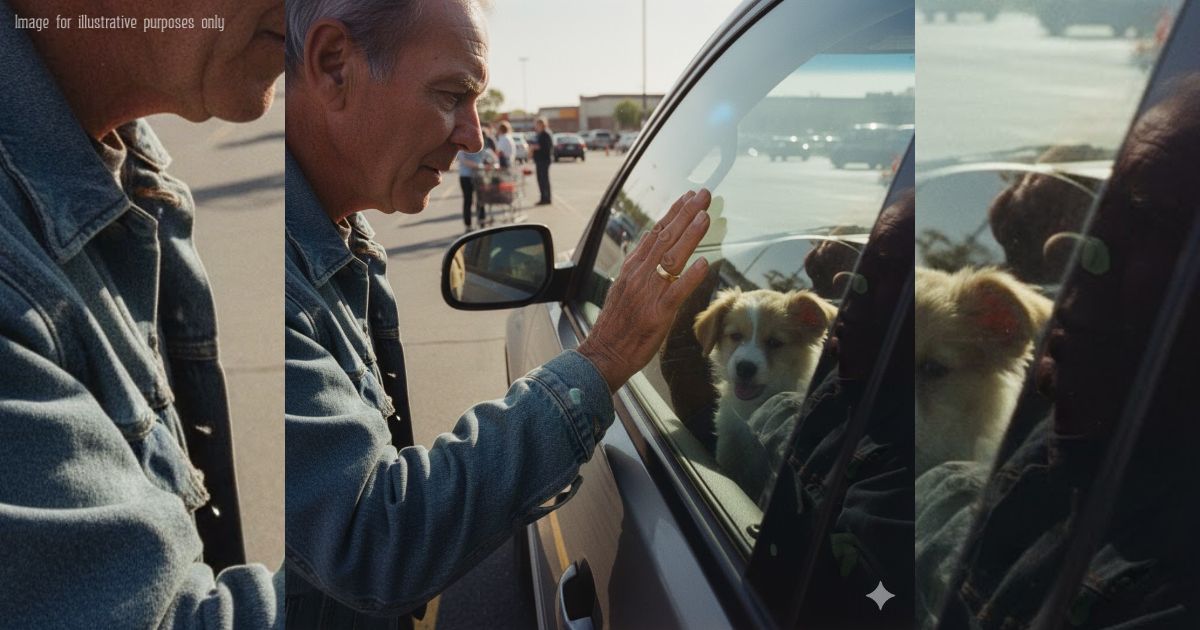

At 104°F, a widower presses his trembling palm to a boiling car window and hears a puppy’s goodbye; he swears he won’t lose another life to heat, not today.

Two minutes is all he has before help arrives, two minutes to choose between waiting obediently or doing something that could haunt him for the rest of his life.

Walt Mercer doesn’t look like a hero.

He looks like any tired grandfather pushing an empty cart across a shimmering parking lot where the air tastes like iron.

Then he hears it—a thin bark, then a whine that sounds like a string snapping.

The SUV’s windows trap the heat like a kiln, and a small golden dog crumples on the backseat floor, tongue dry, eyes cloudy with panic.

Walt’s hand lands on the glass and sears.

He flinches, then plants his old work jacket over the window, making a sliver of shade, a flag of mercy flapping in the furnace wind.

“Stay with me, buddy,” he murmurs through the door seam.

His voice is the soft clack of a carpenter’s pencil against wood, steadying his own fear.

He pulls out his phone and dials for help.

Words tumble—dog in a locked car, over one hundred degrees, still breathing, please hurry.

A teenage kid across the lane freezes, phone midair.

He isn’t heartless; he’s just stunned, then filming, then asking if he should share to get more eyes, more help, anything.

“Call for help,” Walt says, not unkind.

“Don’t turn this into a trial.”

A woman walking past stops and slips off her cardigan, hands shaking.

Walt tucks it beside his jacket, building a crooked canopy that steals back a few degrees.

The dog’s eyes flutter.

Walt leans close and talks the way he once talked to Mabel on the last day, when the vet said there was nothing more to do but love.

He remembers the shape of that room, the odor of disinfectant, the weight of his late wife’s palm on his wrist as the seconds lengthened and then dissolved.

Grief is a hot car with no wind; you learn to open, to let something in, or you suffocate.

Sirens rise like a distant wave.

The teenager—Diego, his name is Diego—keeps the crowd back, voice cracking as he says, “Make room, please, make room.”

An animal control unit swings into the lot, lights low but urgent.

Officer Renée Park steps out with focus that cuts through the glare.

“Everyone stay calm,” she says, meeting Walt’s eyes with a nod that is both thanks and command.

She confirms the dog is breathing, then radios the exact coordinates to the vet on call.

Walt stands his ground, jacket trembling under his fingertips.

He wants to do something reckless, something cinematic, something that might be wrong.

Renée’s tone is calm and practiced.

“We’re here now. Keep shading him. Keep talking. You’re doing the right thing.”

Walt talks about ordinary things—the smell of cut cedar, the way morning coffee tastes on a front porch, the sound a cardinal makes at dawn.

The dog’s gaze flickers toward that voice and hangs there like a sail searching for a breeze.

A small crowd gathers, sweat shining, arguments simmering under breath.

Someone mutters about keys and consequences; someone else says not today, not now.

Diego lowers his phone.

“Sir, what’s his name?” he asks.

Walt doesn’t know, so he invents a promise.

“Sunny,” he says, because the word feels like a door opening.

Officer Park works quickly, coordinating with a second unit.

No drama, no grandstanding—just careful hands, a lawful tool, and a path toward air.

The heat warps time to taffy.

Walt thinks he can count each beat of Sunny’s heart through the glass.

He tells a story he’s never told a stranger—how loneliness has corners, how you walk into them without meaning to, and how a dog once showed him the way back out.

He tells it to keep Sunny awake, to keep himself from falling into the corners again.

A woman rushes up, eyes wet, words tangled.

“I only ran in for a minute—” she says, and then she sees the jacket, the crowd, the officer, the dog, and her voice fractures to dust.

Renée nods without judgment and positions her near the front, close enough to be present, far enough not to block the work.

“Stay with me,” she tells the woman. “We’re going to focus on breathing. Yours and his.”

Walt stares at the dashboard clock through the haze.

Two minutes can be a lifetime, and a lifetime can be two minutes.

The unit signals readiness.

Renée meets Walt’s eyes again. “When I say now, lift the jacket,” she says, “and don’t reach inside.”

Walt nods, jaw set, hands already remembering the weight of parting and the weight of choosing not to part.

Diego swallows hard and stops filming.

“Now,” Renée says.

The lock pops with a small, final sound, like a bead of glass cracking in cold water.

The door opens a hand’s width, and for an instant the parking lot inhales.

The barking stops.

Only the heat hums.

Walt bends toward the shadowed space beneath the seat, searching for the rise of a rib, the twitch of an ear, any sign that a promise can still be kept.

“Sunny?” he whispers, voice barely there. “Do you hear me?”

Something shifts in the darkness, or maybe it doesn’t.

A weight of silence presses back against his name.

He holds his breath and listens, counting the seconds he has left to believe.

Is that a breath—or the sound of a goodbye?

Part 2 – The Breath Between Heartbeats

Sirens fold into the heat like thread through cloth.

Then a flicker—one shallow breath that makes Renée’s eyebrows lift and Walt’s knees go weak.

“Shade up,” Renée says, and Walt lifts the jacket carefully.

Air slides in, not cool but freer, and the little dog’s chest trembles again.

A second officer steadies the door.

Renée uses a practiced grip, no theatrics, just a clean angle that keeps the pup’s airway open as she eases him onto a towel.

“Good boy,” Walt whispers, steady as a metronome.

“Stay with us, Sunny.”

The crowd exhales, then hushes itself.

Diego lowers his phone and steps closer with a bottle of water he doesn’t open, because he’s listening.

“Transport,” Renée calls, and a carrier appears like it has been waiting all day for this moment.

A small oxygen mask—made for pets—slides over the dog’s muzzle, a tiny cathedral of clear plastic.

Walt keeps talking about ordinary things, words with shade in them.

Fresh-cut cedar. A porch before sunrise. The way coffee steam curls like a question mark.

The little dog’s eyes find that sound and hang there.

Renée nods once, businesslike and kind. “We’ve got a shot,” she says.

A woman bursts through the crowd, hair stuck to her forehead, panic knocking syllables out of order.

“I was—just a minute—please—” She sees the mask, the officers, Walt’s jacket, and her voice goes thin as paper.

“Ma’am,” Renée says, guiding her to breathe with her hand.

“In through your nose, out through your mouth. Stay here with me. He’s en route to the clinic. You can meet us there.”

The woman nods too fast, one hand over her mouth like she is holding in a storm.

Walt feels a reflex rise to judge, then remembers the room with disinfectant and the way seconds can turn guilty by accident.

“Focus on the dog,” he says softly, mostly to himself.

“Let the rest wait.”

They load the carrier.

Renée gives Walt a brief look that says both thank you and don’t do anything risky now.

The animal control vehicle pulls away, lights low, not to draw a crowd but to part it.

The woman presses shaking fingers to her temples and whispers, “I’m Jasmine. I didn’t— I swear I didn’t—”

Walt doesn’t step closer, doesn’t step away.

“Go to the clinic,” he says. “Tell him a man with a bad jacket named him Sunny for five minutes.”

Diego touches his elbow like an anchor.

“Should I post?” he asks. “Like… to tell people to watch for this? Or is that making it about clicks?”

Walt looks at the boy’s phone, the thumbnail of a trembling hand, a small dog, a bleeding-hot window.

“Post to help,” he says. “Not to punish.”

They drive to the clinic in a slow caravan that feels like a prayer moving at the speed of traffic.

The lot shimmers again, then disappears behind them.

The clinic’s waiting room is cool the way a library is cool—controlled, protective, intentional.

A staff member meets them with calm eyes and a clipboard that asks only what matters.

Jasmine signs her name like she’s apologizing with every pen stroke.

She leaves the “pet’s name” line blank and stares at it like it’s a verdict.

“New adoption?” the receptionist asks gently.

Jasmine nods. “Five days. I was going to name him today,” she says, voice cracking. “I guess he got one anyway.”

“Sunny’s a good name,” Walt says, sitting on the edge of a chair like the seat might reject him.

“It opens the door.”

Diego hovers like a shadow that can’t decide where it belongs.

He texts his mom he’ll be late, then sits when Walt pats the empty chair.

They wait.

Waiting is its own heat. It finds each person’s quietest fear and warms it by degrees.

A vet tech appears, kind but noncommittal, the professional face of hope.

“Temperature’s coming down,” they say. “He’s responsive. We’re cooling carefully and monitoring.”

Walt nods as if he understands the math of careful.

Jasmine folds into herself, shoulders shaking without sound.

“I ran in for one thing,” she says to no one and everyone.

“One thing. The line was long. Someone asked for help. My mind— I don’t have an excuse. I only have this—” She points at her chest, the place where panic has been living.

“Stories stack,” Walt says after a moment, words feeling their way out.

“You think you’re turning one page and you’ve turned three without meaning to.”

Jasmine looks at him like he has spoken a language she once knew and forgot.

“Do you have a dog?” she asks.

“Had,” Walt says.

“Mabel. She was my wife’s, and then she was ours, and then she was mine, and then she was gone.”

Jasmine’s face softens into something that isn’t self-defense.

“I’m sorry,” she says, and means it.

They are saved from what to say next by footsteps and a practiced smile that is almost relief.

Dr. Alvarez comes out with a chart and a careful tone.

“We’re out of the danger curve,” they say. “He’s going to need rest, fluids, and quiet. But he’s here.”

The word here fills the room like a breeze.

Jasmine’s knees unbend as if a string has been cut.

“Can I see him?” she asks.

“One at a time,” Dr. Alvarez says. “Short and calm.”

They look at Walt. “You too. He tracked your voice.”

Jasmine goes first.

When she returns, her face is wet and lighter, like rain after dust.

“He’s small,” she says, “but he takes up a whole room.”

That earns a fragile smile from everyone within earshot.

Walt walks back with Dr. Alvarez, each step measuring out a separate vow.

Sunny is tucked into a soft pen under a gentle fan, eyes clearer, breathing steady as a song at half-volume.

“Hey there,” Walt says, kneeling, the old jacket over his arm like a surrendered flag.

“You kept your end. Thank you.”

The dog’s eyes find him and soften.

One paw twitches, a tiny yes.

“Keep visits quiet,” Dr. Alvarez says, not unkind. “And please, no online advice threads. We’ll call when he’s ready.”

Walt smiles. “I’m more analog than that,” he says.

Back in the lobby, Diego shows them what he posted—no faces, no license plates, no blame.

Just a caption: “Call for help first. Shade, space, patience. Lives are small and big at the same time.”

Comments begin to stack like chairs after an event.

Some are grateful, some angry, some trying to turn this into a courtroom.

Walt asks Diego to pin the clinic’s general safety tips.

He does, and the thread becomes less heat and more light.

Jasmine signs a consent to allow treatment.

She asks what she owes, the words bruised with dread.

“Let’s talk after we see how he’s doing,” the receptionist says, gentle as gauze.

A donation jar appears on the counter without anyone making a big deal about it.

Walt stands to leave and then doesn’t.

He looks at Jasmine, who looks like she is made of apologies and coffee with nothing in it.

“I’m here every morning,” he says. “At the store down the road. If you ever want to talk through a checklist for hot days. No pressure.”

Jasmine nods, on the edge of tears again. “I need to be better,” she says. “I want to help other people be better too.”

“Start with yourself,” Walt says, as if he is reading from the book he wishes someone had given him years ago.

“Then we’ll see about the rest.”

They step into the early evening.

The heat has softened by a few degrees, the way a song drops from a shout to a hum.

Jasmine walks toward her car with her hands empty and her heart full of heavy things.

Diego peels off toward the bus stop, thumbs still answering comments with a kindness that surprises even him.

Walt lingers by the door with his jacket over his shoulder.

He doesn’t feel like a hero; he feels like a man who remembered how to hold a promise and didn’t let it slide.

A breeze carries the grocery-store smell of oranges and cardboard.

In the parking lot, a child laughs, and someone drops a set of keys and apologizes to nobody.

Jasmine pauses at her windshield.

There is a scrap of paper under the wiper, folded in half like a small, mean letter.

She opens it with two fingers that have only recently stopped shaking.

Black marker. Big letters. Rushed and certain.

WE KNOW WHO YOU ARE.

DO NOT COME BACK HERE.

She looks around without moving her head, as if the asphalt itself might be watching.

Her shoulders rise to her ears and stay there.

Walt sees the paper and the way it rearranges her face.

He takes one step forward, the careful kind that says he will not touch what isn’t his to touch.

“Jasmine?” he asks. “Everything okay?”

She swallows and tucks the note into her bag like a piece of glass she can’t drop in public.

“It’s fine,” she says, which is the exact size of not fine at all.

She nods at him, grateful and embarrassed and burning.

“I’ll be back in the morning,” she says. “If they let me.”

She gets in her car and closes the door like a whisper that meant to be loud.

Walt stands there with his old jacket and the feeling that help arrived for one life today—and might be needed for another tomorrow.

The sky fades to a softer color, the edges of the parking lot no longer a mirage.

Walt breathes in, out, storing the air like a promise he’ll have to keep.

Behind him, a bus hisses as it bends to kneel for passengers.

Ahead of him, the note’s four words crawl into the night and multiply.

He touches the pocket where he keeps his carpenter’s pencil, the one thing that still draws straight lines.

Tomorrow, he thinks. We’ll need better shade. We’ll need a plan.

Tonight, though, he watches the door of the clinic close softly on the last customer.

Down the hill, a siren starts and then stops, as if thinking better of it.

He turns toward home with the jacket over his shoulder and the word Sunny in his mouth like a prayer that hasn’t decided its ending.

Behind him, under fluorescent quiet, a small dog dreams of voices and shade.

Part 3 – Sunny’s First Shade

They called it Heat Watch because “standing guard with shade and water” didn’t fit on a flyer.

It started with three people, a borrowed folding table, and a stack of homemade signs that said in plain letters: Call for help first.

Walt brought his old jacket and a cooler with ice packs wrapped in towels.

Diego hauled cones, laminated tip sheets, and a roll of blue painter’s tape that stuck even when the pavement steamed.

Officer Renée Park stopped by before her shift and walked them through safety again.

“Observe, call, shade if you can,” she said. “Don’t escalate. Don’t confront. We’ll handle the entry.”

Dr. Alvarez emailed a one-page guide that was calm, readable, and almost kind.

It reminded people that heat is physics, not punishment, and that care begins with noticing.

They set up near the grocery lot’s far edge where heat pooled like a shallow lake.

Walt taped posters to a light pole and watched the edges curl, then pressed them flat with the heel of his palm.

Jasmine came at nine with a folded lawn chair and a paper bag of apology muffins.

She kept glancing at the border of the lot like it might have eyes.

“You don’t owe us pastries,” Walt said, cracking half a smile.

“I owe a better morning,” she said, and sat.

People drifted by, curious but protective of their routines.

Some nodded, some frowned, some took a tip sheet like a truce.

A middle-aged man leaned on his cart and asked if they were trying to shame people.

“Trying to keep living things alive,” Walt said, not raising his voice.

Diego offered to set up a QR code linking to the clinic’s safety tips.

Jasmine colored the edges of the sign with a yellow highlighter and said the brightness made her hopeful.

By noon the thermometers clipped to their belts read like bad news.

The metal of Walt’s folding chair stung his fingers, and the air smelled like rubber warmed past remembering.

They practiced quiet scripts, the kind that leave room for dignity.

“Hi there, just a reminder the inside of a parked car can heat dangerously fast,” Walt would say. “We’re here if you need a hand calling.”

Not everyone loved it.

A woman with sunglasses the size of magazines told Jasmine to mind her own business and rolled away.

Jasmine swallowed, nodded, and stayed.

Later she handed a tip sheet to a teenage sitter and showed her how to hold the page so the wind didn’t steal it.

When the afternoon tipped into glare, Renée circled back in her unit.

No emergencies yet, just a few checks, a few second looks, a few doors that clicked open before heat made decisions for anyone.

“Presence matters,” Renée said, leaning on the open window.

“Most folks just need a nudge before the worst becomes ordinary.”

Diego filmed a thirty-second clip of Walt pointing at the sign and nodding toward the sun.

No names, no plates, no blame—only the sentence: Protect before you post.

The clip did numbers faster than they expected.

Comments stacked again, but this time the center of gravity was different.

People asked for printable signs.

A church volunteered their shade canopy; a high school offered art students to draw friendly dog illustrations for the posters.

Walt texted Hannah a photo of the table and wrote, “Trying to be useful.”

She replied with a single heart and then typed, “Proud of you,” and then didn’t send it.

Jasmine drank water like it was a project she could actually finish.

Her phone buzzed without stopping, half of it kindness, half of it something else.

Around three, a white sedan idled near their table.

The driver lowered the window and said, “So you’re the lady from the video.”

Jasmine steadied her voice.

“I was the woman who made a mistake, and I’m trying to make it matter.”

“Internet never forgets,” the driver said, smirking like he was doing her a favor.

“Good,” Jasmine said, surprising even herself. “Maybe it’ll remember this table too.”

He shrugged and rolled away.

Walt kept his gaze soft and his posture open, the way carpenters stand when the nail gun is loaded and nobody needs to know.

Diego checked the donation jar—someone had dropped in enough for more clipboards and a shade umbrella.

He counted under his breath like a kid learning a new language: gratitude, inventory, possibility.

A young mother approached dragging heat behind her like a cape.

She looked at the signs, then at her stroller, then at Jasmine with a face like asking permission to breathe.

“Do you have a checklist?” she asked.

“Something simple I can stick on the dash?”

Jasmine handed her a card they’d drafted that morning.

It said: Keys. Water. Shade. Call. Check again.

The woman read each word out loud like a small vow and tucked the card into her diaper bag.

“Thank you,” she said, and it had a weight to it.

Midafternoon, Dr. Alvarez arrived with a cooler of fruit and a quick update.

“Sunny’s sleeping, temp stable, appetite curious,” they said, smiling with their eyes.

Jasmine covered her face for a second and then didn’t.

“Thank you for letting me see him this morning,” she said. “I didn’t deserve it.”

“Care isn’t a reward,” Dr. Alvarez said. “It’s a practice.”

They left a stack of clinic flyers and promised to email more if needed.

A gray-haired man in a ball cap paced near the table, then stopped.

“Back in my day,” he began, and everyone braced for a speech that would scold the present.

He surprised them.

“Back in my day we were careless too,” he said. “We just didn’t have cameras to show us.”

Walt laughed, short and grateful.

“Cameras cut both ways,” he said. “We’re trying to tilt them toward mercy.”

Clouds learned a new shape but refused to be shade.

The heat index climbed like a stubborn story that wouldn’t change its ending.

At four, a small argument bloomed two lanes over.

A man yelled that he’d only run inside for “a second,” that he could see his dog from the register, that it was “fine.”

Walt walked over with his palms open and his voice nonthreatening.

“We’re not here to cite you,” he said. “We can help you call if you need assistance.”

The dog was pacing, tongue out, eyes glassy.

Renée’s unit rolled in calm as a sentence that knows where it’s going.

She handled it without theater, and the man’s shoulders dropped.

He nodded thank you to nobody in particular and drove off with his window cracked and his pride folded.

Jasmine’s hands shook afterward, though nothing had happened.

Walt gave her a moment without commentary and a cold pack wrapped in a napkin.

“People see what they can handle,” she said finally.

“Sometimes that’s not the whole picture.”

“Sometimes it’s enough,” Walt said. “Enough to move one step back from harm.”

Diego refreshed the clip and saw it had been reposted by a local page that liked feel-good rescues.

The comments were mostly tender; a few were sharp.

He drafted a reply and showed Walt before posting.

Walt read and nodded. “Leave out the sentence that sounds like a verdict,” he said. “Keep the one that sounds like a map.”

By five, they were sun-tired in the way that turns every bench into grace.

They took turns sitting and not sitting, drinking and pretending they weren’t thirsty.

A woman with a lanyard and an official tone approached asking who had “authorized” this.

Walt told her they were volunteers, not enforcers, and that the clinic and animal control were aware.

She didn’t argue, but her eyebrows sketched a warning.

“Liability is real,” she said. “Stay strictly informational. No interventions without authorities.”

“Understood,” Walt said, grateful for boundaries he could trace with a pencil.

Renée had drilled the same thing; they were ready to repeat it until it lived in their bones.

Jasmine packed the muffin bag with the neatness of someone who needed to control a corner of the day.

She kept looking at the lot’s edges, and Walt finally asked if she was afraid.

“Of doing it wrong again,” she said.

“Of people who want me to be only the worst thing I’ve done.”

Walt thought about how grief edits a life until only one scene remains.

“We don’t have to give the edit away,” he said. “We can add scenes.”

They decided to print more cards and a big sign that read TWO MINUTES OF CARE.

Diego sketched a small sun on the corner and gave it smiling eyes.

Before they left, Walt walked the lot one more time the way you sweep a shop floor at the end of a job.

He found a single mitten under a cart and placed it on the bench where someone might remember it.

Jasmine folded the lawn chair and told them she’d be back at nine.

Her voice had steadied into something that could hold a yes.

The sky fell from white to pale gold, and for the first time all day the wind remembered how to move.

They began to break down the table in a slow choreography of tired kindness.

Walt’s phone rang with the particular double-beat that Renée had told them to set for alerts.

He answered before the second buzz finished its sentence.

“Mercer,” Renée said, quick and clear.

“We’ve got a call two blocks over, east lot by the pharmacy, interior reading one-oh-six. We’re en route.”

Walt looked at Jasmine and Diego and did not have to say anything.

They were already lifting the cooler, grabbing the signs, and leaving the cones for someone else to stack.

Traffic hissed like a giant kettle coming to boil.

The sun slid lower but not kinder.

They trotted, not running, not reckless, just fast enough to be the right kind of early.

Walt tucked the old jacket under his arm and tasted metal in the back of his throat.

At the corner, heat rolled up and met them head-on.

Somewhere past the pharmacy entrance, alarm bells of the afternoon clanged in human voices.

Diego pointed.

A small crowd had gathered around a dark sedan, and a woman’s hands were flat on the glass the way hands press on a hospital waiting-room window.

Jasmine stopped to breathe once, twice, steady and practiced.

Her eyes were clear, not from innocence but from choosing.

Walt heard Renée’s unit before he saw it, the soft rush of a vehicle that has learned discretion.

He raised his hand once in a wide, slow arc that said we are here, we are calm, we are ready.

The thermometer on his belt blinked and then settled on its new number like a verdict that hadn’t been appealed.

One hundred six.

Walt tightened his grip on the jacket.

“Two minutes,” he said to nobody and everybody. “Make them count.”

Part 4 – The Weight of Waiting

They reach the east lot at a fast walk that feels like a prayer.

Heat rises off the asphalt in visible waves, and the crowd is already a circle, already a verdict waiting for a gavel.

A dark sedan sits under a sky that forgot how to blink.

The dog inside paces in tight figure eights, tongue lolling, eyes glassy, panting too fast to count.

“Observe, call, shade,” Walt says, the words automatic from practice.

Diego is dialing before the sentence is finished, voice steady as he gives location, description, condition.

Officer Renée Park rolls in without siren, exactly as trained.

Her calm cuts through the heat like a cool cloth, not cold, just certain.

“Space, please,” she calls, hands up and open.

“Everyone take two steps back. We need airflow and room to work.”

Jasmine takes a breath the way she learned to—all the way in, all the way out.

She folds her fear and sets it aside like a towel.

A man hovers near the driver door, keys clutched, face flushed with adrenaline and embarrassment.

“I was inside paying,” he says, voice brittle. “I could see him from the counter. It was only a minute.”

“It gets dangerous faster than it looks,” Jasmine says, keeping her tone soft.

“Can you unlock for Officer Park so she can check him safely?”

Renée nods once, appreciative but focused.

“Sir, step to my right and keep your hands clear when I open. We’ll do this in sequence.”

The crowd murmurs, the human hum of judgment blooming and then wilting.

Diego lifts his phone and lowers it again, choosing. No faces, no blame, just the checklist on the sign.

Walt slides his old jacket against the rear window, making a pocket of shade.

He talks through the door seam to keep the dog anchored. “Hey, buddy. You’re not alone. Good boy.”

Renée works with practiced efficiency, no drama, no improvisation.

A lawful tool, a measured motion, a click that is more relief than sound.

The door opens the width of a palm.

Heat exhales like a furnace sighing, and the dog’s panting stutters, then steadies.

“Mask,” Renée says, and a tech from her unit fits the small oxygen cone with hands that have done this before.

The dog’s eyes flick to Walt’s voice and hold there like a kite catching a low wind.

The man who owns the car steps back, hands shaking the way paper shakes when you try to fold it wrong.

“I’m sorry,” he says to the air, to the dog, to anyone who will take it. “I didn’t think— I didn’t think it was that fast.”

“Fast is the whole problem,” Renée says, kind without loosening her grip on the moment.

“We’ll assess at the clinic. Follow us there if you want updates.”

A voice spikes from the edge of the circle, too loud, practiced in getting attention.

A man with a phone on a short stick leans in and angles the lens at Jasmine.

“That’s her,” he says to his audience, whoever they are.

“The woman from the other video. Guess she likes the attention.”

Jasmine’s shoulders tense, but she doesn’t back up.

Walt steps into the frame like a curtain pulled gently across a window.

“This is a rescue, not a tribunal,” Walt says evenly.

“We keep it educational and calm. You’re welcome to film the safety steps. Not the faces.”

The streamer pivots the camera, trying to catch a flare of conflict.

“What if people need to know who’s doing this?” he says. “What if they keep doing it?”

“Then they’ll see the signs and the steps,” Walt replies, voice low, eyes steady.

“They’ll see a way to do better today. That’s the whole point.”

Renée doesn’t look up.

She and her partner slide the pup into a carrier, securing the latch with a motion that looks like closing a promise.

“Transport ready,” she says into the radio.

“Vitals responding, initiating cool-down protocol. Owner informed, witnesses calm.”

The streamer keeps talking to his lens, but his words don’t land.

The circle has changed shape; it’s less crowd, more corridor.

Jasmine keeps her breath even, counting in a rhythm she learned in the waiting room.

She turns to the man with the keys and offers a small card.

“Hot-day checklist,” she says. “Keys, water, shade, call, check again. Put it on your dash for next time.”

He takes it with a nod that is almost a bow.

“I’m grateful,” he manages. “I thought I was careful. I wasn’t careful enough.”

“Care grows,” Jasmine says, surprising herself with the sentence.

“It grows faster when we share it.”

They load the carrier into the unit.

The crowd breaks apart naturally, people resuming errands with a little more attention in their step.

The streamer tries for one more jab.

“Don’t you think she should be banned from owning a pet?” he asks, heaving the question toward a stranger’s anger.

Walt doesn’t bite, and neither does the lot.

“We’re not banning people from hope,” he says, almost gently. “We’re building shade.”

The unit pulls away toward the clinic, and the heat drops one degree simply because the panic goes with it.

Walt presses the heel of his hand to his eyebrow and exhales.

Diego touches his sleeve, young and old at the same time.

“Want me to post the checklist again?” he asks. “Just the checklist. Just the steps.”

“Pin the clinic’s tips on top,” Walt says.

“Keep the comments on a short leash.”

They walk back to the folding table, the cones waiting like punctuation that hasn’t been used yet.

Jasmine refills the water cooler, her hands steadier now that the emergency has an ending.

“You handled that,” Walt says, and means a dozen things.

The dog. The man. The lens. The old story that wanted to take over.

“I handled what I could,” she says. “The rest belongs to tomorrow.”

She glances at the edges of the lot and then stops glancing. “I’m tired of letting fear drive.”

Renée swings by ten minutes later, windows down, posture loosened.

“Good work,” she says. “Nobody escalated. That’s the difference between help and headlines.”

“Headlines don’t hold water,” Walt says, tapping the cooler.

“Shade does.”

Renée grins, then turns serious.

“If anyone harasses you, call. We’ve got better things to do than play referee, but we will if we must.”

Jasmine nods and slides her phone into her bag where the old note still sits like a coal.

She thinks about showing it to Renée and then decides to give it no more oxygen.

By late afternoon the lot eases from white glare to dull gold.

They pass out the last of the tip cards and promise to print more.

A mother in scrubs takes two cards and pockets one for a neighbor who works nights.

A retired couple asks if they can volunteer in shifts because their knees don’t like standing long.

“Every body has a role,” Walt says, and writes down their names.

“Sit in the shade, be the smile, hand out water. That’s a rescue too.”

Diego checks the post.

This time the comments tilt toward recipes for doing better, not recipes for punishment.

A local teacher messages asking if her students can design posters.

A shop owner offers a canopy and doesn’t ask for his logo on the corner.

When the sun starts thinking about forgiveness, they pack the table in a practiced dance.

Jasmine folds the lawn chair without watching the edges of the lot.

As they load the last cone, a car idles nearby with its window down just enough to mean something.

The driver doesn’t speak, only watches, then lifts a hand in a half-salute and drives away.

“People test the water before they drink,” Walt says.

“Let them.”

They walk the lot one more time, looking for anything that breathes.

Only heat breathes now, lower, less cruel.

Walt’s phone buzzes with a clinic update: the sedan dog is stable, cooling well, likely to go home after rest.

He reads it aloud, and their relief is quiet, like a hymn hummed under breath.

They agree to meet at nine tomorrow with more cards and a bigger canopy.

Diego will print, Jasmine will bring muffins again, Walt will bring his jacket because some superstitions are just memories with a job.

They disperse at the corner where shade finally overrules the day.

Jasmine walks to her car with her shoulders not quite up around her ears.

Walt takes the long way home, the route with more sky.

He likes the way twilight flattens worry into something you can stack and put away for a few hours.

At home, he hangs the jacket by the door and rests his palm on it as if it were a shoulder.

Mabel’s face flickers through memory—not a wound anymore, more like a window that opens.

He makes tea he won’t finish and stands in the kitchen while quiet finds the corners.

The pencil in his pocket reminds him that some lines still draw straight.

His phone buzzes once with a message from Diego: “Checklist post pinned. Comments mostly helpful. I’m learning to delete with mercy.”

It buzzes again with a message from the clinic: “Sunny resting. Temp good. He tracked your voice in his sleep.”

Walt smiles into the empty room.

“You’re doing fine, buddy,” he says to no one, to everyone.

He rinses the mug and lets the water run a second longer than needed.

The house feels less like a museum, more like a shop with a project on the bench.

The phone rings with a different sound, the one he assigned to the part of his life that still confuses him.

He answers before it can decide to stop.

“Dad?” Hannah says, breath catching like a door that needs oil.

“Can we talk tomorrow? It’s about Mom.”

Walt leans against the counter and shuts his eyes to see better.

“Tomorrow,” he says. “Any time.”

“I found something,” she says, voice smaller than he remembers.

“In a box. It’s… I think it’s for you.”

The line goes quiet except for the soft geography of her breathing.

“Okay,” Walt says. “Bring it to the store. We’ll open it together.”

They hang up with a care that feels like lifting a sleeping child.

Walt sets the phone down, then picks it up again, as if it might give him a hint.

He looks at the jacket and thinks of two minutes, ten years, and the distance between a mistake and a map.

Outside, heat unlatches its grip on the street, and the day releases a breath it didn’t know it held.

Walt turns off the kitchen light and stands in the doorway long enough to feel the threshold.

“Tomorrow,” he says to the empty rooms, to the past, to the dog whose name means day.