Part 5 – The Carpenter’s Promise

Hannah arrives before the sun remembers how to be cruel.

She carries a shoe box hugged tight to her ribs like a secret that decided to live.

They meet at the small table near the market’s windows.

Walt sets his old jacket over the chair back and tries to slow his breathing.

“I didn’t sleep,” Hannah says, sitting without settling.

“I kept thinking about what to say and none of it sounded right.”

“Say the wrong thing,” Walt answers, and means it.

“We’ll sand it later.”

She opens the box and the air inside smells like attic and old wood.

There is a folded blueprint, a metal tag on a ribbon, and a short carpenter’s pencil chewed at one end.

The metal tag is small and heart-shaped.

Mabel, it says, and below it a number that no longer calls anyone.

Hannah touches the tag with one fingertip, then lets go as if heat lives there too.

“I found it in Mom’s sewing cabinet,” she says. “I thought I knew every drawer.”

Walt picks up the pencil and it fits his hand like muscle memory.

“Heavy little thing for how short it is,” he says, to keep from saying something else.

Hannah unfolds the blueprint across the table.

It’s a hand-drawn plan for a simple wooden frame with canvas stretched across—portable shade, four legs, cross-braced, quick-release pins.

In her mother’s handwriting it reads: Market Canopy, Walt’s spec, two-person carry.

In the corner, a note: For hot days. For dogs. For us.

Walt’s throat tightens in a place he forgot had nerves.

“Your mother hated the sun,” he says, smiling and breaking at the same time. “She still made room under it.”

Hannah looks up and the years line up between them like boards waiting to be joined.

“I was mad at you,” she says, simple and clean. “When Mom was dying, I thought you loved that dog more than you loved us.”

Walt’s hands go still on the paper.

“I loved Mabel because she was carrying the parts of your mom I couldn’t hold,” he says softly. “But I never put her over you.”

“I know that now,” Hannah says, and for once neither of them has to win.

“I think grief turned me into a hallway with no doors.”

“Grief does that,” Walt says.

“Then one day you find a handle you didn’t remember installing.”

They breathe the same air for a few seconds and call it progress.

Outside, a cart squeaks by like a reminder that the world insists on errands.

Hannah traces the measurement lines with her nail.

“Can you build it?” she asks, voice steady. “The shade frame?”

“I can,” he says.

“And I will.”

She wipes at one eye with the heel of her hand, efficient as always.

“I want to help,” she says. “I can’t stand on asphalt all day, but I can sew canvas. I can make six if you get me the cuts.”

Walt laughs once, the small kind that fixes a hinge.

“Deal,” he says. “Let’s give the sun less to work with.”

They fold the plan carefully and slide it back into the box.

The pencil goes in Walt’s shirt pocket, where a pencil has always lived when he remembers who he is.

Hannah hesitates at the door.

“It’s good to see you doing something that isn’t just surviving,” she says. “I think Mom would like that.”

“Me too,” Walt answers, and the words don’t cut like they used to.

After she leaves, the market seems bigger and lighter.

Walt stacks the morning’s tip cards, checks the cooler, and decides to make one stop before meeting the crew.

The shelter sits behind a row of sycamores that invent their own shade.

A bell rings when he enters, the polite kind that belongs to kitchens and kindness.

A volunteer with a nametag that says Joon smiles and points him toward the senior wing.

“Quiet dogs,” Joon says. “Loud hearts.”

Walt walks the row and each face is a question with four legs.

He answers with names he doesn’t say out loud.

In the last kennel, a brindled dog with a gray mask lifts his head and blinks slow.

One ear is crumpled at the tip like a postcard that traveled too far.

“Sully,” the placard reads.

Age: 10+. Temperament: Gentle. Favorite thing: Leaning.

Sully stands and leans his whole life against the wire with a sigh that sounds like a policy change.

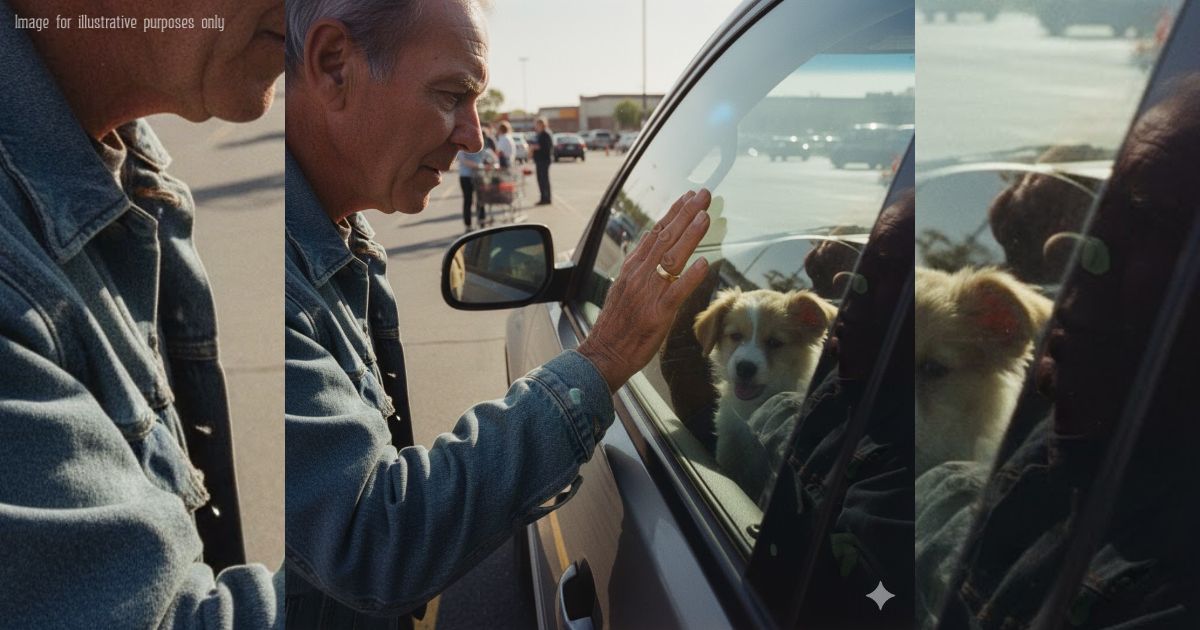

Walt kneels and the old jacket slides off his shoulder like it decided for him.

“Hey, old timer,” he says.

Sully leans harder until leaning becomes conversation.

Dr. Alvarez appears, because of course the world is smaller than we think.

“I moonlight here,” they say, amused. “Helps me remember the stories before the charts.”

Walt smiles up at them, one hand through the wire scratching the place where Sully’s gray grows thick.

“I came to look,” he says. “That’s a lie. I came because the house is a museum without this.”

Dr. Alvarez nods like they’ve heard this page before and liked it.

“There’s a foster-to-adopt program for seniors,” they say. “Cooling Companions. Short-term, monitored, no pressure.”

“Cooling Companions,” Walt repeats, tasting the words.

“It sounds like a fan you plug into your loneliness.”

“It is,” Dr. Alvarez says, not joking.

“And the dog benefits too.”

Walt closes his eyes and finds Mabel and doesn’t run.

He thinks about a house that needs new footfalls and a life that needs new planks.

“I’m afraid of losing again,” he admits.

Dr. Alvarez shrugs with compassion. “You will,” they say, honest and kind. “But in the meantime, you’ll both get found.”

Walt signs the forms slowly, like vows.

Sully watches every pen stroke and approves each one with a soft huff.

Joon brings a harness and a bag with a few days of food and a vet note tucked at the top.

“Take your time,” Joon says. “He likes quiet beginnings.”

Outside, the heat puts a hand on their shoulders but not on their throats.

Sully steps into the day and leans into Walt’s leg like they practiced it.

They walk the long way to the truck because first walks should be long.

Sully pauses to catalog every smell; Walt pauses to catalog every reason this might work.

At the market lot, Jasmine and Diego are already setting up.

A borrowed canopy trembles in the morning breeze like it has an opinion.

Jasmine sees Sully and her face softens the way fabric does after a hard wash.

“Is this a new crew member?” she asks.

“Temporary, officially,” Walt says.

“Personally, I don’t know how to do temporary.”

Diego kneels and offers the back of his hand for greeting like the internet taught him.

Sully sniffs and leans, and Diego’s grin goes all the way to childhood.

They add a new sign to the table: TWO MINUTES OF CARE, now with a little dog drawn in the corner that looks suspiciously like Sully.

Hannah texts to say she’s started cutting canvas; a photo follows with chalk lines and a coffee mug that says You’ve Got This in a handwriting Walt recognizes.

By noon, the tips are circulating like recipes at a block party.

Strangers take extra cards for neighbors they don’t know yet.

Sully lies under the table on a cool mat and commits to the afternoon with dignity.

Every now and then he lifts his head when Walt says “buddy,” as if that’s his real name and he’s just being polite about the paperwork.

Renée stops by and pretends she doesn’t see a dog under a volunteer table.

“Hypothetically,” she says, “if a very calm senior citizen were providing moral support, it would be hard to object.”

“Hypothetically,” Walt says, and Sully blinks like a yes.

They pour water, point to shade, and practice the art of keeping a rescue from turning into a spectacle.

Jasmine speaks to three different people who look like earlier versions of herself and doesn’t flinch.

A man argues and then doesn’t.

A woman listens and then does.

Around three, Hannah appears with a rolled bundle in her arms.

She kisses Walt’s cheek without thinking about who might be looking.

“Canvas test,” she says, unrolling a panel the color of good decisions.

She has sewn the words SHADE IS CARE across the hem in neat block letters.

Diego whistles low.

“We’re going to look like we know what we’re doing,” he says.

“We do,” Jasmine answers, and nobody feels the need to argue the degree.

They take a break in the sliver of shade between canopy and reality.

Sully scoots so his shoulder just touches Walt’s boot, then stops moving like he found home and doesn’t want to jinx it.

Walt pulls the blueprint from his bag and shows Hannah the cut list he scribbled in pencil.

She edits with a seamstress’s mind and a daughter’s right.

“Cross-brace here,” she says. “Less wobble. More forgiveness.”

“Wish we could install that in people,” Walt says.

“You are,” she answers, and it lands.

A city alert pings every phone at once, sharp and official.

EXCESSIVE HEAT WARNING, it reads. ROLLING OUTAGES 1–6 PM. CHECK ELDERLY NEIGHBORS AND PETS. USE COOLING CENTERS. AVOID ELEVATORS.

The lot goes quiet in a way that says everyone read the same sentence and pictured the same apartment.

Renée’s unit chirps with overlapping radio traffic, and she steps away to triage with words.

Jasmine looks at the canopy and then past it to a skyline made of windows.

“People will be stuck,” she says. “Not just dogs.”

“Heat Watch can walk,” Walt says, already counting blocks in his head.

“Shade frames can be door-to-door.”

Diego is typing before he finishes.

“New post,” he says. “Neighbors check neighbors. Pets are neighbors too. Leave politics at home, bring water.”

Hannah squeezes Walt’s forearm, a pressure that says please and also thank you.

“I’ll sew through the night,” she says. “Bring me the cuts, I’ll bring you roofs.”

Sully lifts his head again at the word night, as if he has schedules to consider.

Walt scratches the soft where age has made room and whispers, “We’ve got work, pal.”

The first outage ripples across the block like a breath held too long.

The lights in the market blink and settle into off.

Air conditioners quiet in a chorus that sounds like surrender.

Somewhere, a fan spins down and remembers stillness.

Renée returns with the face she wears when her hands are already full of what’s next.

“Outages have begun,” she says. “We’re activating a welfare check protocol. If you can walk, walk. If you can drive, go slow and keep water in the car.”

“We’re volunteers,” Walt says. “Tell us where we won’t get in the way.”

Renée nods and rattles off cross streets like a map you can trust.

“Watch the high-rises,” she adds. “Stairs turn into mountains. Dogs panic when rooms change temperature. People do too.”

Jasmine ties her hair back with a rubber band she had around her wrist for no reason until now.

“I’ll take the south block,” she says. “I can talk to people without raising the temperature.”

Diego packs the cooler, then remembers to hand his spare battery to Hannah like a relay.

“If comments get messy, I’ll lock them down,” he says, and means more than comments.

Walt looks at the canopy, the blueprint, the dog, the daughter, the lot.

He feels something click that is not a lock but a hinge.

“Two minutes at every door,” he says.

“Ask a question, leave a card, find a life.”

They break the table down in under sixty seconds.

Practice has taught them choreography; necessity teaches them speed.

Sully stands and leans exactly once, then falls into step like a veteran.

Walt feels the brush of a shoulder and decides he is braver with it there.

At the corner, the traffic lights sway dead and uncertain.

A siren limps somewhere and gives up.

A woman waves from a second-floor window with a dog in her arms and a worry on her face.

Jasmine cups her hands and calls, “We’re coming up. We’ve got water.”

Renée’s radio crackles with new addresses.

Heat isn’t an emergency you chase; it’s an ocean you cross one block at a time.

Walt turns to Hannah.

“Bring the canvas to the shop,” he says. “I’ll cut until midnight.”

“I’ll sew until morning,” she answers.

They grin because they have a plan that looks like love wearing work clothes.

Then the second outage rolls through and the stairwell two buildings over goes dark.

A child starts to cry, and a dog answers in a language that needs no translation.

Walt lifts the old jacket like a banner that once was only fabric.

“Let’s go,” he says.

The street breathes hot and human.

Tomorrow is promised 110°F.

Somewhere above them, a window opens, and a voice asks for help without words.

Sully tilts his head toward the sound, and Walt follows.

Part 6 – The Day the Air Stood Still

When the power dies, every breath in the city sounds like a plea.

When the fans stop spinning, a volunteer’s knock becomes the thinnest rope across a boiling afternoon—and Heat Watch learns to climb it, door by door.

They split at the corner with the dead traffic light.

Walt and Sully head north toward the brick walk-ups, Jasmine south to the towers, Diego in the middle with a cooler and a stack of cards.

“Two minutes at every door,” Walt reminds them.

“Ask, listen, leave help behind.”

Stairwells hold heat like held breath.

Walt climbs at a measured pace, resting every flight, Sully’s nails clicking a patient metronome.

On the second floor, a door opens to a woman with a chihuahua under her arm and worry on her face.

“Is there a place to go?” she asks. “My AC’s out and he starts shaking.”

“There are cooling rooms at the community center,” Walt says, keeping it simple.

He points to the card, to the hours, to the number that will send a ride if she needs it.

She nods, relief loosening her shoulders.

“Thank you,” she says to Sully specifically, and the dog accepts the credit without debate.

On four, an elderly man peers through a chain, a terrier barking as if letters could save anyone.

“We’re checking neighbors,” Walt says. “Water okay? Any pets inside alone?”

The man hesitates, then unlatches.

“My wife is napping,” he says. “We keep the dog’s bed by the window for the breeze. Should I move it?”

“Shade helps,” Walt says. “Keep water close. If it feels too warm for you, it is too warm for him.”

They leave a card on the table and a little peace in the hall.

Sully leans once against Walt’s knee, the canine version of a nod.

On six, a teen opens the door with a pit mix who thinks strangers are potential best friends.

The boy admits he’s home alone and nervous.

“Heat makes everything cranky,” Walt says.

“You’re doing fine. Keep your phone charged. Check on your neighbors if you can, from the hall.”

The boy asks if he can help outside later.

Walt grins. “We’ll be back at the lot around five. Bring a hat and your good ideas.”

They descend to the street that smells like summer pushed too far.

Across the way, Jasmine wipes her forehead and waves them over with urgency.

“Elevator’s out,” she says quietly.

“Seventh floor family with a senior shepherd. Owner’s got a bad knee. They’re afraid to move him.”

Renée is already on her radio, calm cutting through the heat.

“We’ll send assistance,” she says. “No carrying down stairs until we’ve got support.”

Jasmine nods and goes back up with a pack of bottled water and a tone that lowers panic.

Walt watches the stairwell swallow her and feels pride do a small, useful thing.

Diego texts updates to their post: cooling rooms open, volunteers patrolling, call if you’re stuck.

He pins a comment that reads, Kindly check on one person and one pet today.

They cross to the next block where a second-floor window is propped with a broom and a beagle howls like a smoke alarm.

Walt knocks gently and the door opens to a man who hasn’t learned rest.

“My wife’s at work,” he explains, words tumbling. “I keep the fan on low, bowls full. He still cries.”

“Dogs narrate,” Walt says with half a smile.

“Sometimes they just want an extra check-in. You’re doing it right.”

The man softens in increments.

He takes a tip card and tucks it under a magnet that holds a picture of his kids in winter hats.

Sully noses a corner of the hallway, pauses, then sits like a librarian with a note.

Walt angles his head.

From behind the next door, a small dog coughs, then falls quiet.

Walt knocks, gentle.

A woman answers, eyes tired but kind.

Her pug waddles out like a loaf of warm bread.

“Just checking you both have water,” Walt says. “It’s extra warm in the halls.”

She smiles, as if someone has just told her the ending to a story she thought had none.

“We’re okay,” she says. “Thank you for asking.” She looks at Sully. “You must be management.”

Sully accepts another promotion without comment.

They move on.

At noon, the air tilts from hot to hostile.

Their shirts stick. Their patience holds.

Renée meets them at a corner with a printed list that didn’t exist an hour ago.

“Reports of high temps on ten through twelve over there,” she says, pointing. “We’ve got folks working elevators. Keep knocking. Call if voices rise.”

Walt thinks of the plywood shade frames waiting in his shop like unassembled sentences.

Hannah is sewing canvas to verbs, and the city might learn to conjugate relief.

They enter a building whose stairwell smells like bleach and birthdays.

On three, a grandmother sits in the hall with a spaniel and a spray bottle.

“Cool mist on ears and paws?” she asks, seeking permission.

“Short, gentle,” Walt says. “You’ve got a good system.” He notes the water bowl’s position in shade and feels reassured.

On five, a young couple with a new baby and a husky hover at the threshold of chaos.

They’re trying to figure out who to cool first.

“Don’t pick,” Walt says softly. “Alternate. Small sips for everyone. Stay near the door for air.”

He leaves two cards and an offer: “If you need an hour, bring the dog down to our table. We’ll watch him.”

They thank him like he’s given them sleep.

He hasn’t. He’s given them a plan, which sometimes feels the same.

Back on the street, the heat hits like a moral test.

Jasmine rejoins them, cheeks flushed but eyes steady.

“Shepherd’s okay,” she says. “Neighbor helped with the stairs when support arrived. We went slow. Lots of breaks.”

She drinks water with intention and checks her phone without letting it decide her mood.

Diego points to the sky where clouds pretend to consider mercy.

“Comments are mostly helpful,” he says. “I’m deleting the blame poems. Pinning resources only.”

“Good edit,” Walt says. “Save the oxygen for action.”

They cut across a block where the sidewalk buckles.

Sully halts and points his nose under a parked delivery van.

A high, weak whine leaks from the shadow.

Walt crouches carefully, keeping his hands to himself, and peers under.

A small dog, ribs visible, crouches in the wheel well, eyes rolled white with fear.

No collar, no tags, all tremor.

“Call it in,” Walt says softly to Diego. “Animal control, frightened stray under vehicle, not safe to approach.”

Jasmine kneels a few feet away and narrates the breeze.

“Easy, sweetheart,” she says, voice low, words gentle as shade. “Nobody’s grabbing you. Help is coming.”

Renée arrives with a humane snare and hands that move like a promise.

No lunges, no drama—just quiet geometry and time.

The dog comes out like a pulled thread, shaking hard enough to rattle his own bones.

Renée settles him in a carrier with a towel and a tone that closes doors on fear.

“Good eye,” she tells Sully, who pretends it was nothing.

Jasmine exhales a breath she didn’t know she was borrowing.

“Clinic will check for a chip,” Renée says. “We’ll post through official channels.”

She looks at their faces. “Eat something salty. This heat takes more than it asks for.”

They nod and share crackers like communion.

The day moves and moves and refuses to end.

At a high-rise, a building manager meets them with gratitude and a handwritten list.

“Here,” she says. “These folks might need a knock. One of them has a service dog.”

They climb again, slower now.

On eight, a door opens to a man with a cane and a shepherd with perfect manners.

“Stairs are hard,” he says, wry. “But we’re okay. He reminds me when I forget to drink.”

“That’s a good partnership,” Walt says, and means it to his bones.

They leave cards, phone numbers, and patience.

They take nothing but heat and the occasional thank-you like a souvenir.

By late afternoon, the city feels softer at the edges, not cooler but cared for.

Their simple tasks have knitted a little net beneath the day.

They converge back at the lot where the borrowed canopy trembles with hope.

Hannah arrives with two finished panels and chalk marks on her sleeves.

“First roofs,” she says, laying the canvas across the table. “The rest by morning.”

She kisses Walt’s cheek, then scratches Sully’s ear. “You, sir, look important.”

Sully leans his entire résumé into her shin.

Walt laughs and forgets to be careful with the sound.

Dr. Alvarez pulls up in a compact car with the clinic’s cooler and a box of spare bowls.

“Updates,” they say. “Sedan dog is stable and headed home tonight. Sunny’s appetite is back. He wagged without permission.”

Jasmine covers her mouth and lets the day drop a gear.

“Thank you,” she says, which contains more than gratitude.

They eat fruit that tastes like a decision.

Diego edits the post title to include TODAY and TOGETHER.

A car idles nearby, the driver watching over the rim of a takeout cup.

He drops his gaze when Walt looks back, then nods once and drives on.

Renée parks under the thin strip of shade that has learned their names.

She’s dusty, tired, and exactly the right kind of steady.

“City’s extending cooling hours,” she reports. “We had a few tough calls, but lines held. Your knocks mattered.”

Walt feels the words land like water on hot metal.

“Good,” he says. “We’ll keep knocking.”

Renée glances at her phone and her mouth sets the way a ruler sets a line.

“Forecast just updated,” she says. “Tomorrow one-one-zero. We’ll have more outages. We’re going to need more bodies and stricter boundaries.”

“What do you need from us?” Jasmine asks.

Her voice doesn’t waver. It’s learned a new shape.

“Presence,” Renée says. “Information. Eyes on vulnerable neighbors. And no vigilante rescue. You call us.”

“Copy,” Walt says, grateful for orders that respect both law and love.

Hannah taps the blueprint tube against her thigh.

“I’ll deliver four frames by noon,” she says. “We’ll aim for eight by evening.”

Diego raises his hand like a student with the right answer.

“I’ll run a sign-up for shifts,” he says. “Keep it short, keep it doable. People give more when you don’t ask for everything.”

They agree on rendezvous points, hand signals, and breaks.

They divvy up streets like bread.

The sun slides down but refuses apology.

They repack the table, lay the canvas carefully, count the cards.

Jasmine lingers at her car, reading the windshield like it might speak again.

It doesn’t. The old note stays tucked away, losing edges.

Walt reaches for his jacket and pauses with his hand in the empty space above the chair back.

He always hangs it there like a superstition, but today it has lived on his shoulders.

He looks at the team and knows the word is too small.

Neighbors, he thinks. That’s the word.

Renée’s radio crackles—new addresses, another stairwell, a dog barking in a hot box that someone used for storage.

She’s already moving.

“See you at first light,” she says. “Drink, rest, cool your rooms however you can. No heroics.”

Walt nods.

“Two minutes and a map,” he says. “We’ll carry both.”

They part under a sky that remembers blue.

Sully hops into the truck and settles with the sigh of a story that trusts its next chapter.

On the drive home, the power flickers block by block like the city practicing breath.

Walt passes the shop and looks through the window at the planks waiting for hands.

He parks, opens the door, and lets the day drain off like sawdust into a pan.

Sully follows him inside and leans, as if he’s holding up a world that leans back.

Walt sets a timer for a short nap he knows he won’t take.

He sharpens the stubby pencil until it’s honest, then writes the cut list clean and large.

Outside, the heat keeps humming like a low drum.

Inside, a man and a dog make shade out of wood and time.

At 9 p.m., a text from Renée: THANK YOU. TOMORROW WE START EARLIER.

Walt replies: WE’LL BE THERE. SHADE COMING.

He tacks the first canvas to a frame and tests the angle with his palm.

It gives cool where there was none.

He looks at Sully and the old jacket and the blueprint in his daughter’s neat corrections.

Tomorrow will need everything.

He flips the sign that hangs in his mind from CLOSED to OPEN.

Then he whispers to the empty room, to Mabel, to every dog who ever taught a human to try again:

“Two minutes,” he says. “We’ll make them count.”