Part 5 – The Creek and the Child

I signed.

The pen felt heavier than it should, like it had been holding its own breath for years. My name traveled the thin road of the line and then stopped where the paper told it to stop. Scout made that small humming sound and laid his head across my wrist as if to say, That’s the right word.

Evelyn countersigned with a steadiness that felt like a porch post. June blotted the ink and slipped the attestation into the folder with the care plan and the chip addendum. “All right,” she said. “Now the room knows who speaks dog.”

Lila and I walked to the fellowship hall while Evelyn stayed back and read the weather report to Scout in that slow, friendly voice that puts the day down gently. The hall smelled like coffee and church-basement soap. Metal chairs stood in a loose circle. Nobody made a speech. People just said their names like they were handing out extra chairs.

Reverend Mike passed a clipboard. There were no lines for money, only lines for time. “Fence-post repairs,” one sheet read. “Rides to clinic,” read another. “Soup, broth, soft food,” said a third. We signed our names under our own needs and under whatever our hands knew how to do. A boy who couldn’t drive offered to sit with dogs and read baseball scores out loud.

It took twenty quiet minutes to fill a week.

When I got home, Scout and Evelyn were parked on the rug like ships at harbor. The sweater had made him proud without making him silly. The radio voice was still talking about cloud cover like kindness disguised as forecast. We slept with the porch light on low and the folder on the table, as if both could keep watch.

Morning came gray, then bright. June met us at the clinic front desk with a smile aimed more at Scout than at me. “Imaging is gentle,” she said. “Think of it as a picture that lets us plan.” She set a towel on the pad and let me stay close enough to keep a hand on his shoulder. He tolerated the cold gel with a sigh, then hummed when I said his name like a prayer you can say out loud in any room.

We were done before he decided he was bored. “Give me a few hours,” June said. “We’ll run this by the doctor, and I’ll call when the picture has words.”

On the way home the sky remembered to rain. Not a performance, just a steady talk. We ate soup with too much pepper and watched the world rinse itself. Scout settled, then stood, then glanced at the door with the kind of look that has always gotten me to my feet even when I planned to stay put.

We took the short walk because that’s the right kind of bravery most days. Down the lane, past the stone fence that breaks like a sentence that knows when to breathe. The ditch was running high and the creek was busy, its brown water full of opinions.

Scout stopped, ear cocked. Not a squirrel sound. Not wind. A thin, human edge on the air that made something in my chest go cold and focused.

He pulled once, not hard, just clear. I followed because I know his verbs.

We turned at the old sycamore and came up on the banks where the ground goes slick after a rain. A small bicycle lay at an angle that made my stomach step back. A child’s voice came from somewhere down where the bank undercuts itself. It wasn’t a scream. Screams are for the first ten seconds. This was the tight, steady sound of someone holding on and calling softly because they’d run out of loud.

“Hello?” I called, already counting my own steps like a man measuring a rope he doesn’t have. “Where are you?”

“Here,” the voice said, and it came from a low pocket of the bank where water tongues at clay. A small hand showed, pale as a fish belly, grip locked on a root the size of a pencil.

Scout barked once, not an alarm, a summons. A pair of joggers rounded the bend at a pace that meant their lungs belonged to them. “Down here,” I called, pointing. “And careful.”

We went slow because fast is how you slide into a problem and stay there. One jogger flattened himself on the muddy edge and reached; the other stripped off his belt like he’d done this kind of thing before and looped it through the first man’s forearms. I lay on my side and anchored my boot against the sycamore root. Scout lay down too, head up, watching, his shoulder pressed against my thigh, his weight making me heavier in all the right ways.

“Hey, kid,” the first jogger said. “You’re doing great. Can you look at me? That’s it. Keep that root. I’ve got your wrist. On three we’re both going to stand up like the ground is ours.”

The child nodded, eyes wide and certain in that way you get when your world narrows to two instructions. We counted. He stood as we rose, and then the bank tried to take him back, and then the belt went tight, and then we were three bodies in a row, and then he was up, and then he was crying because the practical part was over and the floodgates had permission.

Scout licked his knuckles and stepped back like a gentleman giving space. The child—eight, maybe nine—wrapped his arms around the dog’s neck without a second thought. “Hi,” he hiccuped. “You barked me up.”

“Your dog barked us all up,” the jogger said, and nodded at me like I had done something worth nodding at.

The boy’s mother arrived in a rush, the kind of sound you hear when people sprint from hope into relief. She dropped to her knees and covered his head with both hands like he was a candle in a wind. She checked him without scolding him and thanked us without making it a ceremony. “I’ll fix that bank,” she said to the creek, to the world, to anyone listening.

I looked at the bike and lifted it to the grass. Scout watched the water like it owed him nothing and he still wished it well. We walked home slower than we’d come, not because we were tired, but because the air feels different after you’ve borrowed it from somebody else for a minute.

Lila posted a quiet note under the town list. No names. No speeches. “The old dog from the gas station pointed again,” she wrote. “Humans did the pulling. All okay. If you live near the creek, check your edges.”

By afternoon the rain thinned into a mist that made the porch light look like a halo lying on its side. A casserole appeared like a magic trick on the top step with a folded note that just said “For tonight or tomorrow. It keeps.” Behind it, a jar of clear broth the color of patience. Next to that, a bundle of kindling tied with twine and a slip of paper that read “Wednesday.”

June’s call came as the daylight slid down the wall. I answered with the phone on speaker so the room could hear.

“Mr. Halpern,” she said, and her voice had that balanced tone good news should wear when it walks into a house that has known bad. “I have the imaging results. There’s arthritis, as we suspected. Hips and lower spine are talking a little too loudly. There are bone spurs, but no mass, no awful surprises. His organs look like an old truck that still runs when you change the oil and listen for rattles.”

I closed my eyes and let my shoulders do what they needed. Evelyn’s hand found my forearm the way her signature had found mine.

“What does that mean for him?” I asked, careful as if the question could spook the answer.

“It means,” June said, “that with consistent pain control, warm places, slow food, and the right schedule, he can have more good days than bad ones for a while. We’re not stopping the clock, but we’re not at the last sentence yet. I’d like to set up a plan we adjust week to week.”

Scout hummed, and I laughed before I could stop myself. The sound came out like a small cough and then turned into something almost young.

“What’s the plan?” I asked.

“Light anti-inflammatory,” June said. “Joint support. Heat before rest. Short walks to the stone fence and back, maybe one extra turn if he asks nicely. A sweater on cold mornings. A recheck next week. If something changes, we change with it. That’s the whole trick.”

“And the fund?” Evelyn asked softly. “Does it… help here?”

“It helps exactly here,” June said. “It’s built for hospice that isn’t goodbye yet. It covers the imaging, the meds to start, and a few rechecks. The rest we can ladder with the clinic’s kindness fund and the town’s Wednesday list. No one has to be a hero. We just have to be present.”

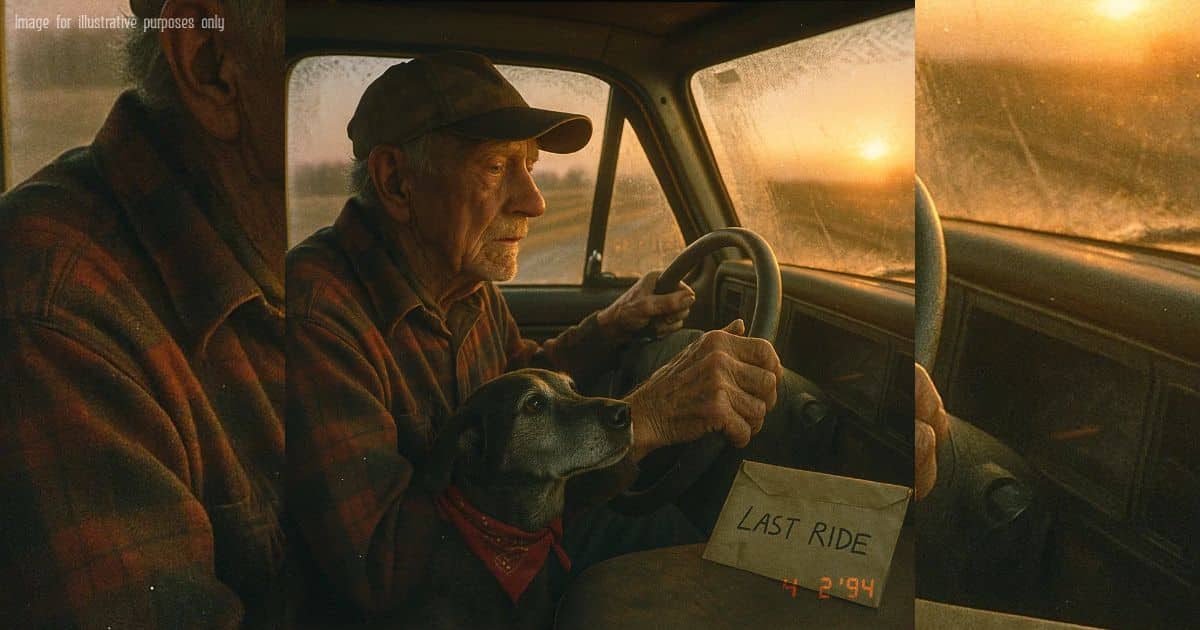

I looked at the kitchen table where the envelope labeled “Last Ride” had become a folded square under a salt shaker. I looked at the sweater and the rice socks and the casserole that kept. I looked at a dog who had pointed twice today and asked for nothing in return.

“Let’s do it,” I said. “Let’s buy him days in a way that spends them well.”

June exhaled into the phone like a smile. “I’ll bring the meds in the morning,” she said. “And a measuring cup with lines big enough to see.”

We hung up and the house held still for a beat, like it wanted to remember this exact air. Lila texted from the fellowship hall to say the sign-up sheet had grown a second page. The boy from the creek sent a photo of his repaired bike with a helmet sitting on the seat like an oath.

Evelyn stroked Scout’s ear and checked the clock. “You two are due for your sun stripe,” she said, and we moved the quilt a foot to meet it. The light warmed his sweater and then his ribs and then his old, faithful lungs. He hummed that hymn and closed his eyes.

Outside, the creek kept talking to itself, a little lower now, a little calmer. The porch smelled like damp wood and pumpkin and the plain goodness of heat.

Then my phone chimed once more with June’s name again, only this time her message was shorter and hung in the room like a key waiting for a hand.

“One more thing,” it read. “If you want it, I have an idea for buying him not just days—but a month that feels like a gift.”

Part 6 – One Last Good Month

June’s “one month” text felt like someone had opened a window in a room I didn’t know was stuffy. When she arrived the next morning, she set a calendar on my table and wrote in block letters across the top: One Last Good Month. She underlined each word once, not twice, like she trusted them to stand on their own.

“It isn’t a countdown,” she said. “It’s a way to spend time on purpose.” She tapped four empty squares for four weeks. “Week One is Warmth. Week Two is Memory Walks. Week Three is Thank You Rounds. Week Four is Letting Go Lightly. We can stretch or shrink days as he tells us.”

She laid out the small medicine cups, the measuring lines big enough to read from across the room, and the rice socks like tools of an honest trade. “We aim for more good hours than hard ones,” she said. “That’s success here.” Scout sniffed the calendar and thumped his tail as if approving the format.

Evelyn brought a shoebox of old things that weren’t heavy but felt like they should be. A photo of Matthew and Scout on a porch that looked different and exactly the same. A red thread she had kept from the first bandana. A small notebook with three pages torn out and a grocery list on the fourth that simply read “eggs, milk, courage.”

“We can use the box,” she said. “Not for sadness. For a sharing kit.” She smiled at the word like it had done something useful.

Lila leaned on the counter and pitched her idea like a young person who knows how to carry a fragile thing without making it a spectacle. “Short clips called Lessons from Scout,” she said. “No names. No addresses. No donation links. Just thirty seconds of something true people can do in their own homes. Like warming a bowl. Or how to build a gentle ramp from scrap wood. Or what hospice for a pet looks like when love keeps its voice low.”

“Love with a low voice,” Evelyn said. “That’s a sermon.”

We started with Warmth Week because winter still had its hand on the door. June showed me how to make the rice socks sing without burning them. She stacked extra blankets within reach of the quilt and labeled a tin “Night Comfort” with a marker. “This is the routine,” she said. “A routine is a promise you can keep even on a tired day.”

The Wednesday crew arrived like quiet weather. No speeches. No pity. A man who fixes things replaced the wobbly porch railing. A woman who bakes left rolls that stayed soft until morning. A pair of teenagers stacked kindling and argued about which end points north like it mattered to the wood. Reverend Mike swept the steps and found only dust, then smiled like dust is proof of work.

Scout supervised, sweater on, nose lifted. He gave each person a polite inspection and a short wag that meant approved. When he tired, he settled with his chin on my boot. The warmth under his ribs answered back with that small hymn that has been teaching me a language all month.

Memory Week began with the stone fence and the break in it where Scout likes to say, “We turn here.” We did. We sat on the stump where my wife used to tie her boots and watched the sun slide along the fence like a finger following a favorite sentence. Scout closed his eyes and inhaled like air is also a story.

The next day we drove the long road around town and let the window down so the old dog could memorize the air again. The baseball field was empty but lined, as if someone had set the world up and then paused it. Scout stood with his front paws on the bottom rail and watched a hop of sparrows take off like a small parade.

A boy on a bike rolled up, helmet shiny and snug. I recognized him, and he recognized Scout, and both of us pretended we didn’t so we could let the meeting be new. “Sir,” he said to the dog, because he’d read Lila’s post. “Thank you for your good ideas.” Scout lifted his chin and the boy saluted in a way that felt invented on the spot and perfect.

We stopped outside the hardware store that isn’t named here because it doesn’t need to be. The owner came to the door with a jar of screws and said he didn’t know what we might need, but he knew life goes better when you have the right size. He gave me the jar and shook my hand twice, once for today and once for the day nine summers ago when a dog walked in like he was an assignment.

Week Three, Thank You Rounds, happened almost by itself. We walked to the church steps on a Sunday when the bell had time to ring without hurrying. People who don’t hug hugged Scout with their words. The clerk from the gas station sat with him on the top step and said “good dog” three different ways that each meant something specific. I thanked him for the detector, and he thanked me for waving people outside without making a show.

At the feed store, Mrs. Alvarez slid a jar of broth across the counter like sliding a boat onto a calm lake. “For joints,” she said, and told me she had put nutmeg in it because her grandmother swore by it, and sometimes grandmothers are right about everything that matters.

Lila filmed bits and pieces with the care of someone making a quilt. She caught hands not faces and tasks not tears. A clip of a slow walk with captions that read, “Short and steady beats long and brave.” A clip of June measuring a pill with text that read, “Small things done on time count big.” A clip of Evelyn holding the radio near Scout’s ear, the caption saying, “Use a human voice.”

Between clips, life kept happening. I repaired a hinge on the barn door because it squeaked at the wrong times and Scout hates surprises. I ate decent food because June threatened me with a lecture delivered with love. Evelyn wrote a letter on good paper with a real pen and folded it into the sharing kit for some future person we do not know yet but already like.

We chose not to teach the creek a lesson again that week because lessons stick better when you don’t repeat them out loud. We walked there anyway and looked at the fixed edge and nodded at the water like it had kept its side of the bargain.

Week Four began with a sunrise that got everything right in the first five minutes. The air tasted like wheat toast. Scout stood, stretched, and handled the porch steps with the grace of a gentleman looking for his hat. He ate well and then rested, and I told him old stories about fence posts and plantings and one stubborn calf that once refused to respect a gate.

That afternoon June came by with a short list and a longer smile. “Letting Go Lightly doesn’t mean leaving,” she said. “It means planning how to hold on in a way that doesn’t bruise.” She pointed to three small tasks. “A soft ramp up to the truck so lifting doesn’t cost him a pride point. A second water bowl near the quilt so he doesn’t ask twice. And a place we agree is the best last spot if the time taps our shoulder.”

We looked at the places together and picked the porch corner where the sun stripe spends the longest time in winter. We didn’t dress it up. We only cleared it of drafts and added one clean quilt that looks like it remembers picnics.

Lila packed the sharing kit. Inside went a copy of the care narrative with blanks so people could fill in their dog’s language. A spare rice sock with a label. A measuring cup with lines a person can see on a bad day. A printout of ideas from the town page that are not money and are all love. Evelyn tucked in Matthew’s red thread and tied the lid with twine.

I felt better than I had in weeks and worse in the hour the wind changed. It happened like heavy weather does, one degree at a time until you notice the window rattling. I carried a small sack of feed from the truck to the back step and the ground did a slow slide under me. Not far. Just enough.

“Sit,” June had told me about my own body. “Sit before you fall, and drink water like it’s work.”

I put the sack down and sat on the step and breathed like a student. The porch blurred and then sharpened. Scout touched his nose to my knee and then my wrist. He does that when he takes roll.

“I’m fine,” I said, because those two words sometimes arrive on reflex like a hiccup.

The next morning I woke before the alarm because old men and old dogs don’t need alarms when habit is faithful. The house was quiet in that good way that means all the important machines are sleeping properly. I made oatmeal and ate it like a responsible adult and poured half a cup of coffee, no more.

We drove the memory loop one more time for the week and stopped at the field where the wind always builds a sentence. Scout watched it write and looked pleased with the grammar. On the way home I felt the edge again, smaller but there, like a note you can hear under the music if you’re listening for it.

I told nobody because I planned to rest and because telling people turns small things into big ones and I have never been good at asking for help twice in a row. We made it to the porch and I lifted Scout down with the blanket and he pretended to resist because ritual matters.

The sweater had snagged a bit on the button and I bent to fix it. Buttons are simple, and I wanted to give the day one more simple thing done right.

The room narrowed without warning. Sounds stepped back. The floor rose just enough to confuse my feet. I reached for the rail and my hand found air that should have been wood.

Scout saw it first. He gave a small sound I had never heard from him, not the hymn, not the thirsty paw, not the “turn here” yawn. A sharp, bright note meant for emergencies and not for much else.

I went down to one knee and then to both. My head said, Stand up slowly. My legs said, Pick another plan. The porch light flickered like a helpful idea. The rice sock steamed on the stove and the clock tried to measure the moment into something containable.

Scout barked the emergency note again, then again, bigger. He launched his careful old body at the screen door and pawed it open like a trick he had saved for when tricks mattered. He trotted off the porch with purpose and turned toward the nearest house with the porch swing that creaks. He barked in a rhythm I recognized from the creek and the gas station, a pattern that says, Come now, come now, come now.

I lay down because the floor and I had agreed on that. The sky over the porch blinked in and out like a badly tuned radio. I heard a screen door bang across the yard and Lila’s voice calling my name, steady and close. I heard Evelyn say, “I’m here,” the way you say it to keep the world from breaking into pieces.

The last thing before the world tilted fully was Scout’s bark cutting clean through the air, old and strong and exact, calling the neighbors the way a bell calls a town. Then footsteps, and hands, and a voice in my ear that made the space smaller and safer.

“Stay with us, Walt,” June said, somewhere near and real. “Scout’s got you. We all do.”