Part 7 – The Letter in the Hymnal

Neighbors filled the doorway before the echo of Scout’s last bark finished crossing the yard. June crouched at my shoulder with steady hands and a calm voice that could’ve talked a storm into folding its wings. Lila held the screen door open like it was part of the plan.

“Light-headed?” June asked. “Any chest pain?” I shook my head and tried to make air behave. The world sharpened in small clicks, like a camera deciding on focus. Evelyn knelt where Scout could see her, one hand on his collar, the other on my sleeve.

A pair of first responders arrived with a kit that looked like a lunchbox for serious days. They checked the simple things first and spoke to each other in sentences that didn’t frighten anyone. “Let’s get him looked at,” one said, and nobody argued with sense.

I didn’t ride in the ambulance because pride still keeps spare change in my pocket, but I let them follow me to the clinic where people fix people. June rode along in her car and called ahead so nobody had to raise their voice when we got there.

Tests happened in soft light with words that stayed human. The doctor asked about breakfast, about water, about whether I’ve been pretending I’m made of wire. I answered as honest as a man can when he’s been a fence post for most of his life.

“Rest,” the doctor said, but not as a scold. “Eat on time. Take help when it knocks. Your body’s asking you to listen. It’s not failing you, it’s flagging you down.”

I promised like a student who wants to pass the class on the second try. June wrote down instructions in letters big enough to read on a tired morning. She slid the page into my jacket pocket and patted it like a seatbelt.

When we pulled back into my drive, Reverend Mike was sitting on the porch steps with his hat off and a small book on his knee. He stood when he saw us and held the book like a palm-sized secret. “I found this where the hymnals live,” he said gently. “Tucked in a spine that’s been opened by your family more than any other.”

He offered it to me. It was my wife’s handwriting on good paper, the kind she kept for recipes and big news. The date was from a winter when we were still two and Scout was new. The first line was not fancy, so it went straight in.

“If you’re reading this, it means the days got real,” she’d written. “Here’s what I need you to remember when your stubbornness is taller than your love: the right kind of letting go is a form of keeping.”

I sat down because the words invited chairs. Evelyn folded herself onto the step beside me with the quiet of someone who knows that reading is work. June leaned against the rail and looked away just enough to make the porch feel like a room.

“She goes on,” I said, and they nodded like a choir that already knew the melody. “She says if I ever get scared of Scout’s last day, I should think about our first day with him instead, and match the kindness. She says if I am the one who goes first, I am to hand him to a woman with a good radio voice and honest eyes.”

Evelyn smiled the kind of smile a person wears when a letter knows her name without saying it. Lila sniffed once and blamed the wind.

“She says to call it mercy when it is mercy and not to call it something else to make it easier on myself,” I read, and the sentence sat down right where it belonged. “And she says that if the house ever feels too quiet, I should stand in the porch corner where the sun stripe lasts the longest and listen for the hymn Scout makes when he’s most himself.”

I closed the book and kept it closed for a minute because sometimes paper needs to cool the way bread does. The porch took one slow breath for all of us. Scout lowered his head onto my boot and hummed like a small radio tuned to the only station that matters.

“That letter’s a compass,” Reverend Mike said. “You don’t have to argue with a compass. You just decide to trust it.”

We made coffee and poured mine into a cup that promised not to run away. June set a timer on her phone labeled “eat something” with a chime that sounded like a friendly knock. Lila wrote “porch sun stripe” on the care plan in the corner as if it were medicine, which I think it is.

The town’s Wednesday list kept working even while we sat. A neighbor dropped kindling by the woodbox like a secret that wanted to be useful. A quiet pair from the fellowship hall replaced two porch screws that had held too many sentences. The gas station clerk sent a text that read, “When you need fuel, tell me. We’re neighbors; that’s the brand.”

Evelyn stayed while I napped because that’s what the letter said someone like her was made for. She sat on the rug with Scout and read him the weather in that low, trustworthy voice. He slept with his paw touching her shoe, manners intact even unconscious.

I woke to the smell of something warm and honest. June had heated the rice socks and set out the pill cup with the right half-pieces, no more. “We’ll walk the short loop later,” she said. “Right now your job is to do nothing bravely.”

After supper, Reverend Mike returned with a shoebox tied in twine. “A different find,” he said, setting it down. Inside was a folded church bulletin from years ago with a note in my wife’s hand. “If Walt forgets, remind him to ask for help twice,” she’d written. “It’s not nagging, it’s insurance.”

I laughed, and the laugh turned into a cough, and the cough turned into something that washed my face a little. “All right,” I told the room. “I’ll ask twice when it matters.”

Lila tapped her phone and showed me a draft for the next small video. The screen showed hands, not faces, rolling a bath towel and sliding it under an old dog’s hips like a dignified lift. The caption read, “Borrow strength, don’t borrow pride.”

“Post it,” I said. “Make it nine seconds shorter so people try it with their hands instead of just watching with their eyes.”

June pointed at the calendar where One Last Good Month looked less like a plan and more like a place we’d been living. “Tomorrow starts Thank You Rounds in earnest,” she said. “If you’re up for it, we’ll do a gentle route. Porch to church to feed store to the baseball fence. No speeches. Just presence.”

Evelyn reached into her purse and pulled out the red thread she’d saved from the first bandana. “Tie this to the new one,” she said. “It’s not ceremony. It’s continuity.”

We sat with that a while because some gifts weigh more than they weigh. I tied the thread where the knot would rest easy against Scout’s chest. He tolerated the fuss and then held still in a way that felt like he understood.

The night settled with two stars and a moon that made the fence line honest. I slept in the chair beside Scout because the letter said to stop pretending I didn’t need to. He slept as if someone had read him a manual for how to be at ease.

Morning came with a sky the color of postcards. I ate oatmeal and the rest of my pride. June arrived with a measuring cup and a smile that said we were sticking to the plan. The sweater went on without catching, and for reasons that would make sense to a poet, the buttons felt like small victories.

We took the route like a procession that didn’t want attention. At the church steps, Reverend Mike pressed my shoulder and said only, “Good morning.” At the feed store, Mrs. Alvarez swapped me a jar of broth for a story about her grandmother’s dog who refused to die until everyone had told him one happy thing.

At the ballfield, the boy with the fixed bank and the fixed helmet saluted Scout with those two fingers kids use when they understand respect without a manual. Scout stood taller for that and I tucked the picture somewhere behind my ribs.

We circled past the gas station where gratitude now lived under the awning like a resident. The clerk lifted a hand and didn’t make it a moment. That’s the highest form of thanks where I’m from.

Back home, we sat in the porch corner the letter had named. The sun stripe behaved just as promised. Scout hummed his hymn, low and certain, while Evelyn read the forecast even though we could see the sky ourselves.

Lila’s phone pinged with replies to the nine-second video. People sent pictures of rolled towels and old dogs with soft eyes. No brand tags. No sales talk. Just kitchens and living rooms doing little mercies on purpose.

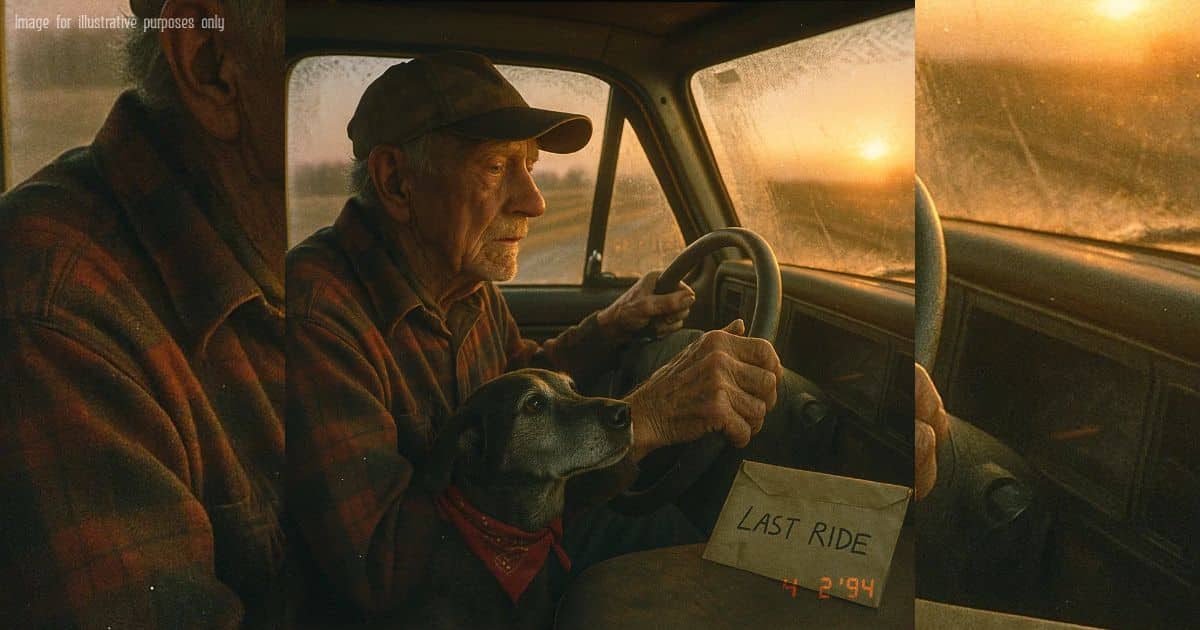

June adjusted the calendar and drew a small star on the day after tomorrow. “If you’ve got gas and gumption,” she said lightly, “we could try something like a slow loop around the places that built your years. A one-truck parade for two passengers. I cleared it with the clinic so we pace the day right.”

“A last ride that isn’t last,” Evelyn said, and I nodded because the phrase landed where it should. The letter had called it mercy. The calendar called it Week Three. My bones called it something I could still do well.

I looked at Scout and at the red thread and at the corner where the light lingers. The envelope labeled “Last Ride” sat under the salt shaker like a story that had learned new words. I touched it once without unfolding it.

From the road, a neighbor’s truck honked the quiet honk that says, I see you, not the loud one that says, Look at me. Lila checked the weather app and grinned. “Tomorrow’s clear,” she said. “Golden hour will show up exactly on time.”

June stood, gathered her things, and left the rice socks lined like soldiers near the stove. The house felt ready, not brave in a loud way, just ready.

Scout lifted his head and pressed it into my palm. He held it there until my hand stopped pretending it didn’t need to hold back. “All right, old friend,” I told him. “Tomorrow we’ll thank the roads. Tonight we’ll thank the porch.”

He hummed once and closed his eyes. The sun stripe reached exactly where the letter said it would, and sat with us as if it had been invited months ago.

Part 8 – The Thank-You Route

We started before the sun made up its mind. June warmed the rice socks, Evelyn checked the sweater buttons like a mother hen, and Lila set the ramp against the truck with a small nod that said, This is dignity, not fuss. Scout lifted his front paws, let me help his back end, and settled into the blanket like a gentleman taking his seat.

June stuck a card on the dashboard that read “Slow Vehicle—Memory Route,” big letters, no drama. She looked at me over the top of her glasses and said the two rules again: stop before tired, and joy counts as medicine. I promised like a man who had learned that keeping promises is a kind of breathing.

The town wasn’t waiting with banners. It was better than that. A porch light here, a wave there, a coffee mug lifted in salute from a stoop that had seen a thousand mornings. We rolled past the church first because habit can be holy. Reverend Mike stood on the steps with his hat off and placed one hand on Scout’s forehead the way you quiet bees, then squeezed my shoulder once like punctuation that knows its job.

At the hardware store, the owner set a small brass tag on my palm, the kind you can tie to a collar with a bit of string. On one side he’d stamped SCOUT, and on the other a single word: THANKS. No sign, no register, just a gift made of metal and intention.

We eased by the feed store and Mrs. Alvarez came out cradling a jar wrapped in a dish towel like a warm loaf. “Bone broth,” she said, and waited for me to say I didn’t need it so she could ignore me politely. I didn’t make her work for it. “For joints,” she added, tapping the lid. “And for men who are pretending they don’t like soup.”

The baseball field was lined but empty, chalk crisp as a fresh shirt. A handful of kids leaned on the fence, all elbows and attention. The boy from the creek stood front and center with his helmet clipped like a promise. He raised two fingers to his brow because he’s been practicing respect, and Scout answered with a small bow he’d learned long ago from a man who taught him manners with biscuits.

Lila filmed ten seconds of the bow and then put her phone away like a person leaving a garden gate open on purpose. “That’s enough,” she said. “People can fill in the rest with their own hands.” June checked the clock and then didn’t. We were making good time, the kind that isn’t measured.

At the gas station, the clerk stepped out with a paper sack and a grin he couldn’t iron flat. “Decaf, doctor’s orders,” he said, holding up a lidded cup. “And chicken for the professor.” He scratched Scout’s chest where old dogs carry their secrets. “Sensors are replaced,” he added softly. “Your nose beat the machine by a mile.”

We took the long road past the grain silos where wind makes its own hymn. Scout leaned into the window and tasted farms he hasn’t walked in years. A farmer on a tractor lifted two fingers off the wheel and it meant the whole paragraph: I see you, I know, keep going.

The creek turn came sooner than I remembered because good days shorten miles. We pulled over on the shoulder and stood at the fixed bank without turning it into anything. The boy’s mother was there with a rake, pressing new grass into the cut like stitches. She waved once, eyes bright and ordinary. “Looks better,” she said. “Thank you for pointing.”

Evelyn rode shotgun with the radio low, reading the forecast in between landmarks. “High clouds moving in from the west,” she murmured, voice like a quilt. “Chance of a system tomorrow night. Today is ours.” She tied the tiny red thread to the new brass tag and let it clink once against Scout’s collar so the moment would have a sound.

We stopped at the cemetery because I asked and because some parts of a map are not negotiable. We didn’t go far, just to the fence line where I could see my wife’s name without making the day bend. I stood, and then I sat on the bumper, and then I told her the plan out loud so the sky could hear it too. Scout hummed low and steady, and Evelyn set her hand on my back the way you steady a ladder without saying anything about heights.

Back in the truck, Lila bumped my elbow with a to-go cup of something warm and sweet and good for people who had signed promises. “From the fellowship hall,” she said. “Anonymous goes down easy.” June handed me a small pill at the right square on the calendar and watched me take it with the kind of bossy kindness I now understand is love.

We hit Main Street at a pace that would disappoint a parade and thrill a hummingbird. People did not line up, because this is not that town, but it turned out this town knows how to show up without making a scene. A mechanic ducked out and tightened two screws on my license plate with a flourish. An older couple on a bench clapped once, politely, like at the end of a hymn that landed. A child in a stroller squealed “dog!” with the exact emphasis the word deserves.

At the clinic, June’s coworkers stepped out just to say hello, no white coats, no clipboards, only hands that know how to help. One slipped me a spare measuring cup with thick black lines and said, “Just in case one walks off.” Another offered a folder pocket with a sticker that read COMFORT PLAN and smiled like bureaucracy can be tender if you try.

We took the last leg past the old ballfield from my youth, the one with splinters in the bleachers and a backstop that remembers better arms. I told Scout about a double I hit in a season nobody recalls, and he listened like it mattered because to him it does. Memory is a team sport if the dog rides shotgun.

By noon the sun had decided to be generous. We parked by the empty fairgrounds and ate sandwiches that tasted like bread, salt, and relief. Scout had his broth like a gentleman sipping tea. He licked the rim once, for manners, and then looked at me as if to say, You’re doing it right.

Lila captured a nine-second clip of the ramp, no faces, just boards and boots and a dog stepping down without losing a single inch of pride. The caption she typed later read, “Build a slope where life made a step.” June nodded at that like it was a prescription she wished she’d written.

On the way home, the road rose and fell like a breath. I felt good tired, the kind you earn. Scout’s head found my knee and stayed there, and the hum came and went like a tide that knows the shoreline by heart. Evelyn tucked the care narrative back into the glovebox and smiled to herself as if she had heard a voice that didn’t need a radio.

We pulled into the drive to find a cardboard box on the porch with three words on the lid: “For Now, Gently.” Inside were things that know how to help without asking how. A small lantern with fresh batteries. A packet of oatmeal with a note that said “Add cinnamon.” Two hand warmers and a knit cap that would fit a head not quite as stubborn as mine.

Reverend Mike wandered up from the fence line with a hammer in his hand and pretended he’d just been fixing a nail that didn’t need it. “I like that cap for you,” he said. “You’ll look like a man who knows where the woodpile lives.” He peered at the western horizon and cleared his throat. “Weather radio says we might practice being neighbors again tomorrow night.”

Inside, the house felt like it had grown bigger by exactly the size of gratitude. June laid the calendar on the table and drew a small check beside “Thank You Rounds,” then wrote “Rest” across the afternoon in letters soft enough to sit down. She refilled the pill organizer, tucked the brass tag into her notes, and pressed two fingers to Scout’s shoulder as if counting something she liked the sound of.

We napped, because honest work ends that way. Scout took the sun stripe like a king with a modest court. I dozed in the chair with the knit cap over my eyes and let time pass without resisting it. When I woke, Evelyn was warming the rice sock and humming a tune that had no words and didn’t need any.

Lila returned close to dusk with a printed sheet she had named “Neighbor Tricks,” a list of tiny acts that solve actual problems. Rubber mats on slick steps. A bell on the back door for dogs who whisper when they need to go. A reminder to charge phones before the wind starts boasting. She’d left off anything that smelled like charity and kept everything that sounded like competence.

We ate soup that tasted like someone loved the pot. June checked Scout’s paws for cracks and his eyes for the easy brightness that means a day did its job. The sweater was still buttoned. The brass tag chimed once when he shook, a sound like a small thank-you from metal to air.

Evening laid its weight along the roof. A line of clouds stacked over the far fields with the look of a sermon you can’t sleep through. The weather voice on the radio kept its calm, but the word “advisory” wore boots. Reverend Mike checked the lantern and nodded at its warm little heart. Lila set an extra water bowl near the quilt because storms make everyone thirsty.

I stepped onto the porch and let the dark try its best. The wind had changed in that way old bones can tell before curtains do. Somewhere past the church you could hear a loose sign knocking a rhythm. I ran my hand over the new railing and felt the new screws catch light like constellations you can touch.

Scout joined me and leaned his shoulder into my shin the way a friend tells you to look up. We stood there and counted to twenty because counting gives nervous air something to carry. Behind us, June’s calendar lay open to tomorrow with a penciled note: “If the lights drop, we keep the hymn.”

The porch bulb flickered once, thoughtful, then steadied itself. The weather voice said the line you wait for and hope not to hear: “Storm watch in effect after midnight.” Evelyn put another blanket on the chair without making it a scene. Lila tucked the phone charger under the end table with the satisfaction of a mechanic.

“Tomorrow we stay put,” June said, not asking. “We make soup early, we fill the thermoses, and we keep the radios honest.” She rubbed Scout’s chest and smiled at me like she could see the worry and had already made space for it.

I touched the brass tag and felt the word stamped there press back: THANKS. The day had been enough. The road had understood. The town had practiced the old art of being there without getting in the way.

The wind gathered its choir out near the silos. The first cold drops found the porch rail and sounded like coins in a shallow dish. Scout hummed his answer and lay down with his nose toward the door that leads to the light.

We closed the house to the weather and opened it to the night. Somewhere in the dark, a screen door banged and then settled. The porch lamp threw a small circle of gold and dared the storm to argue. And in that circle, on the corner the letter named, a dog and a man waited quietly with everything they needed set within reach.