Part 9 – The Storm and the Lamp

The storm arrived like a promise kept. Wind pressed its face to the windows and spoke in a voice that had practiced all afternoon. We put the lantern on the table, the batteries in their place, and the rice socks near the stove like little engines of mercy.

June walked us through the plan again without making anyone feel small. Thermoses filled, soup made early, phones charged, radio tuned to the calm voice that never gets excited. “If the lights drop, we breathe first,” she said. “Then we move.”

The lights blinked once, like a polite knock, and went out. The house made that soft sound it makes when the hum of everything stops at the same time. June clicked the lantern and the room gathered close around its small gold circle like a family choosing the same page.

Scout stood and did his slow patrol of the rooms he trusts. Bedroom, kitchen, back door, front door, then back to me for his roll call nose. He pressed the top of his head into my hand and hummed low, as if to tell the dark it would have to ask permission.

Neighbors arrived the old way, with knocks and voices instead of notifications. Reverend Mike stepped in with a canvas bag and a grin that had kept more than one storm from getting ideas. “Lantern oil and a spare battery,” he said. “No sermons. Just light.”

Lila taped a handwritten list near the door in thick marker. North fence—sound. Mrs. Garner—needs hot water when the kettle cools. Gas station—closed early, clerk home safe. “We’ll add as we learn,” she said, and set a timer to ask the questions again.

The boy from the creek texted from his mother’s phone before the towers got fussy. “We are ok,” it read. “Helmet is on. Thank you to the dog.” Lila showed me the message and then tucked the phone away because lightning prefers people who forget metals.

The wind found a loose sign somewhere up the road and taught it a rhythm. Rain lifted the smell of earth and old leaves and the last of summer from the yard. Evelyn read the weather in a voice meant for one room and one dog. “Gusts through two,” she murmured. “Then a long sigh.”

We made our camp in the living room like travelers who know what matters. Quilt on the rug, sweater on the dog, a second bowl near the lantern so he didn’t have to ask twice. June mixed his evening pill into a spoon of pumpkin and said, “Small, steady, soon,” like she was naming three saints.

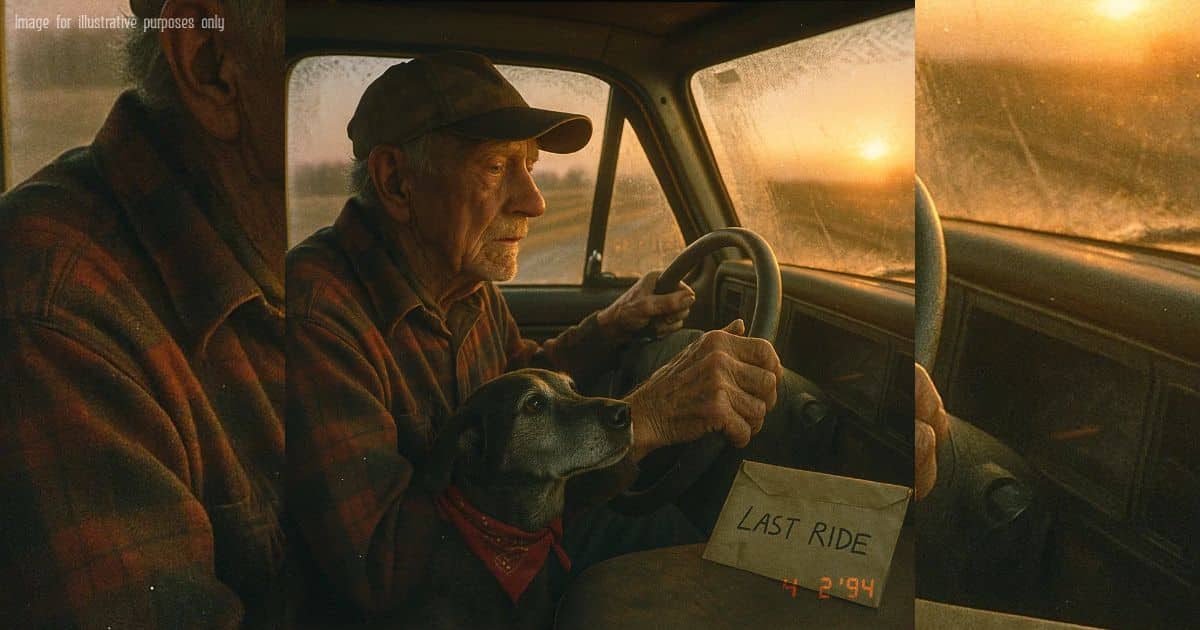

When the radio voice paused to breathe, I took out a pad and wrote by lantern light. My wife’s letter sat beside me like a compass that didn’t mind being used twice. I wrote a note to Evelyn in my square farmer’s hand: if I go first, Scout’s map lives in this house, but his language is already in your pocket.

Then I wrote to Scout without pretending it was silly. “If the day asks too much,” I told him on paper, “you can set your head down and go. You’ve taught me everything I need to know about staying. I won’t make you teach me leaving longer than you want.”

June pretended to fuss with the radio so I could blow my nose without giving a speech. Evelyn folded both notes once and put them in the folder with the care plan as if filing them under something called Courage. Lila refilled the thermos and wrote “sips” on a sticky note like the word could remind a man to take his time.

Around eleven, the porch rattled and the house answered back with the particular creak it saves for weather. Scout stood and placed his paw on my boot, not pushing, just reminding. We moved to the corner the letter had named and settled on the quilt while the lantern threw its coin of light against the wall.

Reverend Mike sat with his back to the door like a hinge. He didn’t pray out loud. He told a small story about fixing a porch step in ’98 while the rain made the roof honest. “You do what helps,” he said. “Then you wait with the kind of patience that knows its job.”

The first big gust leaned on the house like a man testing old wood. We all breathed; the house held. Somewhere a transformer popped its faraway pop and the dark agreed to stay. The dog’s hum found its way under my ribs and set up a steady work there.

At midnight, the radio gave the kind of update that respects thinking people. Downed branches, standing water, hold the road for morning. Lila wrote “stay put” in big letters and taped it beside the door list so nobody had to say it twice. June checked my color and told me to drink water like it was a chore worth doing well.

At one, the rain found its rhythm and forgot some of its anger. Scout slept, then woke, then made a small circle and lay back down with his nose toward the door. He has always liked to face the place where the world comes and goes, even when he plans to stay.

I told him the story about the stubborn calf again because repetition is comfort when the wind practices scales. He blinked slow at the funny part where I lose the argument with a rope. Evelyn laughed politely at a joke she’d heard, then laughed for real when Scout sighed like he would’ve handled the calf himself.

Around two, a light flickered on across the street like a neighbor’s star. The church bell was quiet but near, as if it had decided to keep its breath for the morning. The lantern’s circle grew smaller as our eyes learned the dark better, which felt like a lesson hiding inside a fact.

The storm gave back small things first. The ping of rain softened into a hush. The loose sign up the road made a gentler song. The wind kept a steady conversation with the trees but stopped interrupting. We kept the lantern low to save its heart and our own.

Lila slipped out to the porch with Reverend Mike and checked the tie on the trash can lids because raccoons enjoy storms in unhelpful ways. They came back wet and smiling and alive to the ordinary. “Your railing is strong,” she said, tapping it like a drummer.

Scout stood to check the house one more time and then came back to me with a new quiet in his eyes. He set his head on my knee and left it there longer than usual, not testing, just choosing. I stroked the ridge of his brow and felt something settle that had been hovering for days.

June watched his breathing with the eyes she uses when she counts without frightening anyone. “He’s comfortable,” she said softly. “He’s doing the old dog work. We’ll keep the heat on his hips and the room kind.”

Evelyn read the final weather report of the night. “Tapering after three,” she said. “Clouds thinning before dawn.” She folded the paper and placed it under the lantern base like a faith small enough to fit in a palm.

I lay down fully on the quilt because pride had lost the argument fair and square. Scout shifted to put his chin in the soft of my wrist the way he does when a day has asked a lot and given enough. He hummed once, faint, then again, fainter, like a tide that knows the shoreline and likes it.

We stayed that way through the longest hour a clock can hold. The house breathed. The lantern licked its wick and behaved. June dozed upright and woke every few minutes like a mother who doesn’t apologize for being good at her job. Lila scribbled a list of tomorrow’s small tasks and titled it “After,” then tucked the paper away so it wouldn’t try to hurry us.

At four, the rain let go of the roof the way a tired hand releases a rope. The radio voice said “clearing,” which is a word that can mean weather and also everything else. Reverend Mike refilled the lantern and set it lower still, making a circle no bigger than a dinner plate.

“I can sit the next watch,” he offered, and June nodded without surrendering her post. “Trade with me in half an hour,” she said. “This is a good kind of tired.”

Outside, the world put itself back together in the dark. Somewhere a branch lay where a branch didn’t use to be, and that could be tomorrow’s story. Inside, the quilt warmed the floor and the floor warmed the room and the dog warmed my wrist.

I told Scout the little truth I had saved for when the house was quiet. “You did it,” I whispered. “You found the gas. You found the boy. You called the neighbors when I couldn’t. If you choose to rest now, I’ll call it what it is. I’ll call it mercy.”

He breathed in with that tiny hitch old dogs get when the air has to make decisions. He breathed out steady and soft, like a good sentence ending where it should. The brass tag on his collar chimed once against the button of the sweater and turned the word there into sound.

Dawn began without asking our permission. Not bright yet, just the first idea of light along the kitchen edge. The lantern’s circle meant less and the windows offered more. The house knew it and loosened its shoulders.

Evelyn rested her palm behind Scout’s ear and touched the red thread with two fingers like a blessing. June set the rice sock aside because heat was no longer the point. Lila stood in the doorway and watched with the reverence you save for high places.

I slid my hand to Scout’s muzzle the way June taught me, gentle and sure. His nose was cool and perfect and still the same dog’s nose I’d kissed a hundred times without counting. I felt his breath move against my skin—light, then lighter, then so light it was almost a memory.

We held the silence like a shell to our ears and listened for the ocean we knew by heart. The storm had passed; the house had kept us; the night had done its work. The morning waited in the windows for the next right word.

Part 10 – What Stays

Dawn pressed one careful finger against the kitchen window. The lantern’s circle faded until it was just a memory of gold on the table. Scout’s breath moved once against my wrist, then again, lighter, and then the room learned what quiet really means.

We did not rush the moment or dress it up. Evelyn set her hand behind his ear and touched the red thread like a benediction. June watched his chest with the gentlest eyes I’ve ever seen and said, in a voice meant for one room, “He’s home.”

I laid my forehead on his, the way a man thanks a field after harvest. The brass tag tapped the sweater button and made a tiny sound like a distant bell. “Good dog,” I said, and the words went where they needed.

We let the morning come the rest of the way. Rain had rinsed the sky clean and the fence line wore a stripe of light like a ribbon someone earned. Lila stood in the doorway with her phone in her pocket and her hands empty on purpose.

No speeches, no hurry. June showed me how to wrap him in the quilt like a veteran of ordinary courage. We carried him to the porch corner my wife’s letter had named and set him down where the sun lingers longest in winter.

Reverend Mike arrived without knocking, hat in hand, eyes soft as cedar. He didn’t try to make poetry out of a thing already sacred. “Mercy,” he said simply, and that was the whole service.

We sat with him until the stripe warmed the brass and the red thread. The weather voice on the radio said, “Clearing,” as if it had been listening all night. I remembered the note I’d written and slid it deeper into the folder with the care plan, as if courage needed filing.

By midmorning the town was awake the way towns wake after storms: checking fences, counting branches, making coffee with confidence. Neighbors stepped onto porches and lifted mugs toward each other like lighthouses. Nobody asked for details. Everyone already knew the important part.

The fellowship hall opened its doors without a flyer. Folding tables appeared as if the floor had grown them. Someone spread brown paper and wrote two words at the top in block letters: Scout’s Shelf.

It was a small idea that fit, finally, into a big day. One table for pet food, another for rice socks and measuring cups with thick black lines. A basket of knit sweaters labeled “Gentle Sizes,” a stack of flyers titled “Neighbor Tricks,” and a copy of the care narrative with blanks for new dogs’ languages.

Lila printed nine words on a sheet and taped it to the wall: “No pity. No forms. Take what you need. Share back.” June stamped COMFORT KIT on three plain folders and slid in copies of the hospice plan, the towel-lift diagram, and the short list of things you can do when it’s three a.m.

The gas station clerk carried in a box of lantern batteries without ceremony. Mrs. Alvarez stacked jars of broth until the table looked like a library of warmth. The boy from the creek set his helmet on the shelf edge and wrote a note that said, “For long walks that are short.”

Evelyn brought the brass tag and tied it to a string on the front, where it could ring the word THANKS against wood whenever the door opened. She stood there a minute, palm flat to the shelf, like a person checking a horse’s flank for the calm of it.

People came quiet and left quieter. A man with a beard took a measuring cup and looked relieved, as if precision itself had been heavy. A teacher in a long coat tucked a rice sock into her pocket as if it were a secret that could save a night. No one kept score. The shelf did its job.

Back at the house, June helped me fold the quilt in a way that felt like respect and not like packing. We chose a small place under the maple where roots hold ground without asking for attention. The earth was soft from the storm and smelled like Sundays.

We didn’t make markers that shouted. We tied the red thread to a low branch where birds will argue about it come spring. I touched the brass tag at the hall in my mind and let the sound travel back to the maple like an echo that knows geography.

The day moved forward because days have their orders. June set the calendar on the table and drew a line under One Last Good Month. She wrote one more sentence in neat, careful print: “We kept the hymn.”

I ate soup because people who love you set bowls in front of you and the right answer is yes. Evelyn washed the spoon like it had done good work. Lila wiped the counter and left the cloth draped just so, the way kitchens signal that everything is ready for later.

Afternoon found me in the porch chair with the knit cap down low and my hands empty in the best way. The house had that after-storm hush that makes every floorboard sound like a memory. I shut my eyes and listened for the thing my wife promised.

It came quietly, not from the radio or the road. A hum, low as breath behind a closed door, barely there, exactly there. The porch warmed my shoulder and I understood what she’d meant: the right kind of letting go is a form of keeping.

In the days that followed, grief behaved like weather—arriving, passing, circling back with familiar clouds. I did small chores on purpose. I drank water like it paid me. I walked to the maple in the morning and told a dog what the forecast said, because some habits are prayers.

Scout’s Shelf learned its own hours. An older man in a chore coat borrowed a sweater for a terrier with opinions. A widow took a towel-lift diagram and came back a week later with cookies and a story about dignity on stairs. The teen who offered baseball scores started a list of “voices that help dogs sleep,” and the first entry was “the weather at half-volume.”

Lila posted short clips that taught more than they asked. A hand warming a bowl, captioned “Kindness also comes in degrees.” A ramp built from scrap wood, captioned “Build a slope where life made a step.” A quiet room with a nightlight and a sleeping dog, captioned “Use a human voice.”

No crowdfunding links. No speeches. Just useful mercy.

The clinic kept a copy of Scout’s care narrative and tucked blank pages behind it. June told me people were filling them with the particular languages of their old souls—how Daisy taps the water bowl twice, how Buddy needs the radio tuned to baseball, how Rosie won’t eat unless the spoon is warm.

On Sundays, Reverend Mike needed fewer words and used them anyway. He said a town is measured by the way it treats its old souls—human and otherwise. He didn’t point at me. He didn’t have to.

One afternoon, the boy from the creek appeared at my porch with a bag of apples and the solemn urgency of nine-year-olds on missions. “Mom says thank you again,” he said, helmet crooked, chin steady. “And I wanted you to know the bank held.”

“It did,” I said. “So did you.”

He looked at the porch corner and touched the rail the way you do a monument in a city far from here. “I liked the dog,” he said, plain as bread. “He barked me up.”

“He barked all of us up,” I said, and we let that be enough.

A month turned into two, the way seasons do when you don’t try to speed them. I slept better than I expected, worse than I pretended, and just right on the nights when the maple printed pattern on the grass. The knit cap learned the shape of my head and the chair learned when to creak.

Now and then a rescue group called the clinic about a dog that needed a place to finish gently. June would send a folder with a rice sock, a measuring cup, and a copy of the care narrative with blank lines. Evelyn would tuck a small note inside that read, “The hymn is teachable,” and tie it with a bit of red thread.

People asked if I’d get another dog. They asked the way neighbors do when they don’t want to pull a scab but want to hand you a bandage. I told them the truth: I’m letting the silence talk first. I’m not alone in a house that knows a language.

On the first warm morning of early spring, I walked to the fellowship hall with a jar of pickles I’d owed the world for too long. Scout’s Shelf had thinner rows because the shelf was doing its job. I set the jar down and straightened the brass tag so THANKS faced the door.

A woman I didn’t know took a rice sock and smiled a tired smile. “First night,” she said. “We’ll learn.” I wished her what we had learned to wish for people like us: more good hours than hard ones, and enough light to carry the rest.

On my way out, I stopped at the church steps without meaning to. The bell rope hung inside, the length of it frayed where strong hands have told the town good news and bad. I put my palm against the white paint that still peels in a handsome way and said, “Thank you,” to air that knows how to deliver messages.

When I reached the porch, the sun stripe had found its spot without needing help. I sat in it and let it keep me. The house breathed. The maple held the road. Somewhere, a child laughed, and somewhere else, a dog told someone what the day required.

I put my hand on the rail and felt the new screws hold like promises. The wind moved through the maple in the same slow voice that tucked me in the night Scout called the neighbors. It carried a hum so light you could mistake it for your own heart.

If you asked me the lesson, I’d tell you it isn’t a lesson. It’s a practice. Buy the days you can and spend them well. Call it mercy when it is. And when the time comes to let go, keep what’s true by doing it for someone else.

The red thread still hangs low on the maple, waiting for birds with ideas. The brass tag rings THANKS when the fellowship hall door opens and shuts all day. And in this house, in the porch corner my wife named, the sun keeps its appointment, and an old hymn stays learned.

Thank you so much for reading this story!

I’d really love to hear your comments and thoughts about this story — your feedback is truly valuable and helps us a lot.

Please leave a comment and share this Facebook post to support the author. Every reaction and review makes a big difference!

This story is a work of fiction created for entertainment and inspirational purposes. While it may draw on real-world themes, all characters, names, and events are imagined. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidenta