They handed me my father’s folded flag at noon. By sunset, his K9 had curled up on my socks like he’d chosen which part of my life to guard.

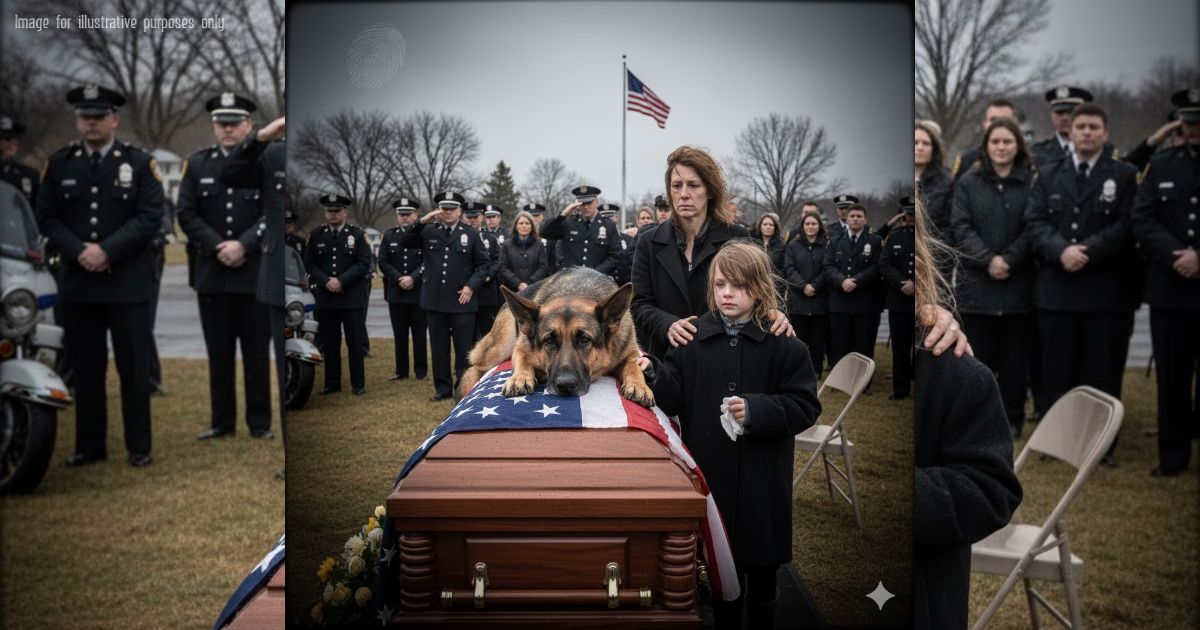

The flag felt heavier than it looked—triangle-tight, corners perfect, blue deep as a winter sky. I was nine and trying to hold it the way the officer showed me, but my arms shook. The honor guard stood so still that the world seemed to balance on their shoulders. Wind moved the trees above the cemetery and caught in my mother’s hair. She didn’t brush it away. She just held my elbow like it was the only railing left on a steep set of stairs.

Sergeant Hall unclipped Ranger’s leash and the big German Shepherd stepped forward. He didn’t heel or sit. He walked straight to me, lowered his head, and pressed it against my knees. A small sound—half sigh, half prayer—came out of his chest. I didn’t mean to cry then. I had promised myself I wouldn’t. But Ranger breathed on the damp edge of my black tights and I cried anyway, and when I did he leaned harder, as if someone had told him the new command for my life was simply “stay.”

That night, Mom made tea and didn’t drink it. The house knew he was gone. The clock in the kitchen ticked too loud, and the porch light flickered twice and then decided to stay steady, which felt like an apology. Ranger paced from room to room, checking windows the way Dad used to lock them, then returned to my doorway, circled once, and went down with a grunt. His head rested on my socks that had been kicked off under the bed. I fell asleep listening to his slow breathing, and when I dreamed, Dad was putting his hat on Ranger’s head and laughing in the way you can hear and feel at the same time.

The days that followed were slow and fast in the wrong places. People brought casseroles and cookies, and then the casseroles stopped and the bills came. Mom started taking extra shifts at the grocery store. She smiled for customers and smiled for me and for Ranger, and then, when she thought neither of us could see, she let her smile rest on the kitchen table like a heavy bag of oranges she needed to set down.

At school, my class made cards with bright stickers. I put them in a shoebox under my bed with Dad’s old baseball cap and a photo of him leaning over Ranger with a training sleeve on his arm. “Good boy,” he’d written on the back in blocky letters. I traced the letters with my finger so often that the paper began to thin.

The first Saturday after Dad’s funeral, Sergeant Hall came by with forms. The department had retired Ranger from service and transferred him to us. “He’s earned a couch,” Hall said, scratching the fur behind Ranger’s ears.

Ranger closed his eyes and leaned into the hand like a door swinging to its frame. “You know,” Hall added, looking at my mom, “your husband always said Ranger had two switches: ‘Work’ and ‘Watch My Family.’ You won’t have any trouble sleeping with him around.”

That was true. We slept, and when we didn’t, Ranger kept us company. He had his own habits. He did a quiet sweep of the house before bed, sniffed at the baseboards, checked under the table, then picked a place to sleep where he could see both the hallway and my door.

When I woke from a bad dream, his ears lifted before I even sat up. He would stand, touch his nose to my wrist, and go back to his post. On the nights when Mom’s car rolled in late and the cold air followed her inside, Ranger did a little shoulder dance of relief in the kitchen before settling down again.

On a Tuesday, our school librarian asked if Ranger could join “Reading Hour.” I brought him on a short leash and a pocket of treats I was very serious about not giving him until he “earned” them. The kids from my class sat in a circle on the carpet, and I read a letter I had written for Dad. It wasn’t long, just a page about my math test and the new art teacher who wore bright earrings that jingled when she laughed.

My voice shook at first. Then it steadied. When I got to the part where I wrote, “I miss the way you knock on the door when you come home, even though you have a key,” Ranger exhaled and put his chin on my shoe. We all looked at him at once, and then at me, and I felt something open in the room, like a window that had been stuck was suddenly free.

Life went on imperfectly. There were kindnesses and sharp corners. Not everyone in town agreed on everything about the badge my dad wore, but even the people who didn’t agree held the door open for my mom when her hands were full.

At night, lights bloomed on porches for the holidays. Our building was old and honest about it; the paint on the stair rail was thin from years of hands. Mom talked about saving for a different place, one with newer wiring and a backyard where Ranger could run. I drew pictures of it for her and taped them to the fridge.

The night it happened, the air had that clean, cold smell you only get when the temperature drops under freezing. The porch lights of our street were strung with soft colors. We had set a little tree in the corner of the living room. Ranger had studied it like a puzzle the day we brought it home, then accepted it as one more thing to watch.

Mom was on a late shift. I finished my homework at the kitchen table, put two extra treats in the jar for Ranger “for tomorrow,” and went to bed. Ranger lay in the hall, his head outstretched, ears twitching to sounds I couldn’t hear.

I don’t know how long I slept. I remember a dream about Dad teaching me to ride a bike without training wheels. In the dream I kept saying, “Don’t let go,” and he kept saying, “I won’t,” and I believed him.

Then Ranger barked, one short round sound, not loud but with a kind of bell inside it. I sat up. The room looked normal. Then I smelled something not normal at all.

Smoke doesn’t begin with a roar. It begins with a whisper. It put a thin line down my throat and made my tongue feel chalky. Ranger shoved his nose against my shoulder and pulled at the sleeve of my pajama top with his teeth, gentle but certain. “Okay,” I said. I swung my legs out of bed and he moved the way water moves downhill—purposeful, quiet, fast.

In the hallway, a haze had gathered near the ceiling. Ranger touched his muzzle to my knee and lowered his body, showing me to crouch. I did. We moved together toward the living room where the tree lights were off but a darker shape seemed to move along the wall like a slow shadow.

The old heater hissed. Ranger left me by the front door and sprinted down the hall to my mom’s room, which was empty, then returned and pawed at the deadbolt. He whined once, low, and then turned, headed for the kitchen.

The back door off the kitchen sticks in the best weather, and this wasn’t the best weather. Ranger braced himself, threw his shoulder into it, and I felt the door give a little, then more. He looked up at me, and I understood: push with him. We put everything we had against that old door, and it opened to the cold, clean night.

“Stay.” That’s what I said to Ranger, and he did not. He ran past me back into the hallway. I heard the scrape of his nails on the wood, a sound that scares you in a bad movie but steadies you in real life.

I yelled for Mom out of habit, and then I remembered she wasn’t home yet. I coughed. Ranger came back with my coat in his teeth. He dragged it into the kitchen and nudged it toward me until I put it on. Then he was gone again.

I realized who he was going to find—the neighbors on the other side of our thin wall, Mr. and Mrs. Alvarez, who were older and moved slow.

I wanted to stop him. I wanted to go with him. I was nine and not brave enough to do both. I stood in the open back door, the cold wrapping around my knees, and then I heard voices out front—someone shouting my mom’s name, and then the slam of a car door, and then footsteps fast on the porch. Sergeant Hall’s voice reached me like a rope.

“Maya! Where are you?”

“Back door!” I shouted, but my throat made it small. He appeared a second later, a big shape in the smoke. He took one look at me, one look at the old furnace closet, and then he grabbed a heavy flashlight from his belt and went in the direction Ranger had taken.

The world became a quick collage—red and blue lights painting the street, the cold, my breath, my mother’s car sliding to a stop at the curb, neighbors in coats, hands covering mouths, a chorus of quick prayers.

Ranger reappeared in the kitchen doorway, head low, flank singed, a fine gray dust on his back like he’d rolled in chalk.

Behind him, Sergeant Hall guided Mr. Alvarez carefully; Mrs. Alvarez followed in a blanket jacket, coughing but upright. Hall’s voice was still steady. “You’re okay, you’re okay.” The fire crew shouldered in. A wave of cooler air moved through the apartment as they opened every door and window they could.

My mom reached me then. Her arms went around me and the coat and the cold. “I’m here,” she said, more than once. “I’m here.” She didn’t cry until Ranger limped over and put his head under her hand. He leaned his weight into her fingers, and her tears landed on the fur between his eyes and vanished there.

At the hospital, a nurse dabbed ointment on the tender places on Ranger’s paws and wrapped them in neat white socks. The doctor listened to Mom’s lungs and nodded. “Rest,” he said. The word sounded like a gift. Sergeant Hall sat on a plastic chair with his hands on his knees, as if he didn’t trust them to be still anywhere else.

By morning, the apartment smelled clean again. The fire hadn’t eaten the building, thanks to quick work and luck, but it had taken a corner of our living room and a chunk of our fear and replaced both with something sobering and bright.

The next week, the town’s church groups and the PTA and the corner hardware store put their heads together. They replaced old smoke detectors in our building and a dozen others on our block. A local nonprofit started a fund for K9 safety gear. A retired electrician named Earl did work on weekends “for the families who have a lot of month left when the money runs out.” He said it with a smile that made you believe in good hands.

At Ranger’s follow-up appointment, the veterinarian clipped the bandages and gave him a biscuit he accepted only after looking at me for permission. I nodded and he crunched it, content. The vet said, “He’s on duty, isn’t he?” I said, “Always,” and felt proud in a way that made my shoulders lift.

At school, I brought Ranger again for Reading Hour. This time, other kids brought letters too. One wrote to her grandfather. Another wrote to her brother who’d moved to a different state. The librarian listened the way you listen to rain on a roof, quiet and grateful. Ranger took it all in. He protected the sound like it was something you could guard with your body.

On the day the apartment was finally safe to come home to, we stood in the doorway a long moment before stepping in. The walls were patched, the paint fresh, and the tree had been relocated to the curb where volunteers in red hats collected things to be mulched and spread in the town park.

Mom hung our photo of Dad and Ranger back up. The glass had cracked in the fire, a thin line down the middle, but we decided to keep it. “It looks like a lightning bolt,” I said. “Or a road,” Mom said. “A road we crossed.”

That evening, when the light went soft, I put the folded flag at the foot of the couch and read Dad a letter about everything that had happened—about Earl the electrician, and the new detectors, and Mrs. Alvarez bringing us cinnamon bread, and the way Ranger now tapped the kitchen floor twice before each meal as if reminding us that routines are a kind of love.

Mom listened with her hand on Ranger’s back. Ranger’s ears turned toward me whenever my voice dropped. The house breathed with us.

I asked Mom if we could keep the little crack in the photo just as it was. She said yes. “Not everything needs to be perfect to be true,” she said. The words settled around us like a blanket you’ve owned long enough to trust.

Sometimes I still dream I’m riding that bike and saying, “Don’t let go,” and sometimes I wake up before Dad answers.

On those nights, Ranger stands and comes over and places his head on the couch cushion, right where the flag meets my knees. I rest my hand on the space between his eyes and feel the steady, warm shape of him there.

My father chose to serve this town. Ranger chose to keep serving what my father loved most—us. When people ask me now what a hero looks like, I think of a triangle of blue cloth, a cracked picture frame, a street lined with fresh smoke detectors, and a dog who sleeps facing the door. I think of the sound his paws make on the floor when the house is quiet: a soft, regular tapping, like a heartbeat you can hear.

Dad is gone. His watch isn’t. And every evening, when Ranger takes his post by the hallway and the porch light holds steady, our home remembers how to glow.

Thank you so much for reading this story!

I’d really love to hear your comments and thoughts about this story — your feedback is truly valuable and helps us a lot.

Please leave a comment and share this Facebook post to support the author. Every reaction and review makes a big difference!

This story is a work of fiction created for entertainment and inspirational purposes. While it may draw on real-world themes, all characters, names, and events are imagined. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidenta